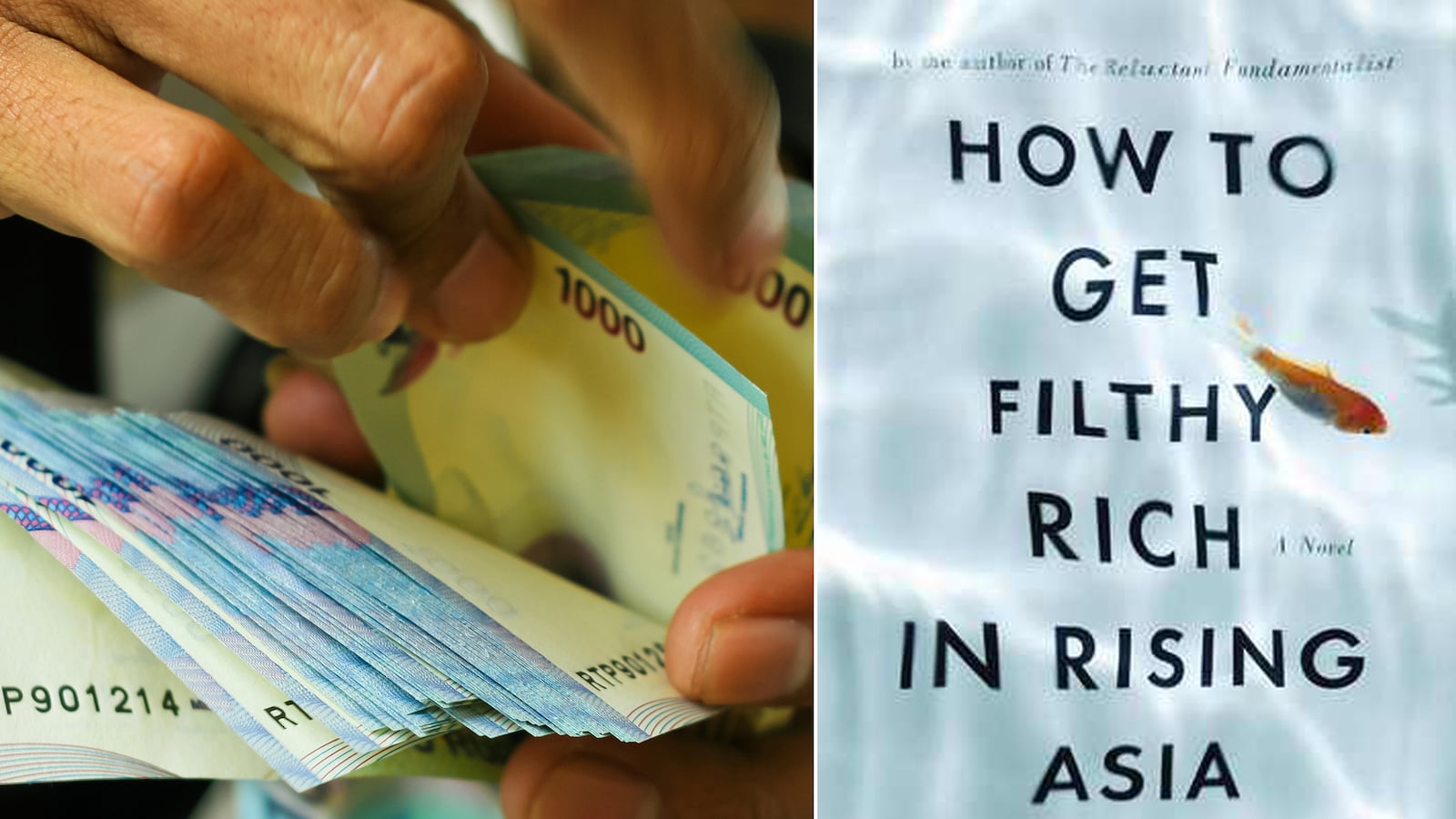

Near the midpoint of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, the narrator asks you from the second-person point of view: “Is getting filthy rich still your goal above all goals, your be-all and end-all, the mist-shrouded high-altitude spawning pond to your inner salmon?”

Of course it is; “you” were born a pauper in a disease-ridden slum of an unnamed Asian country, and by the time the book makes sure that you want to proceed, you have worked hard to get where you are, first as a counterfeit DVD delivery boy and then as a salesmen of just-recently-expired comestibles. You’re not about to bail off of the track to filthy wealth just because it’s becoming apparent that in order to reach your goal of Western-style opulence you will have to make more and more concessions of morality, legality, and humanity. Money means more to you than just status or new toys; it is freedom, a way out of squalor for both you and your family.

The book, though, wants the best for you. It is, after all, a self-help book, or at least it refers to itself as such, even though it acknowledges right from the start that such a thing is oxymoronic and can never really exist. The best it can offer you is a low-resolution road map, exemplified by the titles of its chapters: “Move to the City,” “Get an Education,” “Learn From a Master,” “Be Prepared to Use Violence,” etc. The details you will have to figure out for yourself. “For our collaboration to work,” Hamid writes, “you must know yourself well enough to understand what you want and where you want to go.”

Soon you realize that the real ticket to the big time isn’t shady second-hand goods, but rather the source and sustenance of life itself, especially precious in rising Asia: water. Beginning your entrepreneurial operation boiling and bottling in your own two-room home, you are soon overseeing drilling operations down into the aquifer yourself. You do contracting work with the military, providing hydration for their rapidly expanding operations. (Rising Asia requires rising defense budgets.) Your empire is built on top of a large and intricate system of bribery, force, and bureaucratic finesse, of which you have turned out to be a master. Naturally, your new heightened station in life requires heightened security, and you sleep in your large house behind barbed wire and under the watch of armed guards.

Your life, from your birth until your death, contains the outline of a love story, in the person of the “pretty girl,” who is from your village and whose life yours intersects with about every decade or so, but she is presented less as a fully rounded person and more as the embodiment of the age-old economic motivator of the promise of sex, another shining brass ring.

That is, until your last meeting, both of you beggared and on death’s door. It is only then, when unfettered capitalism has shown you a wonderful time and then abandoned you completely, that you realize the gravity of your mistakes and the true costs of filthy wealth—the ugly, final part that Horatio Alger left out.

You the reader knows that the second-person narrative is tricky, but soon you recognize that Hamid is achieving the same effect of innumerable facelessness that Jay Mcinerney was praised for in his 1984 novel Bright Lights, Big City. But where the latter novel ushered you though a city in the full flush of comfortable late-capitalist hedonism, in Hamid’s you could be any in a sea of billions of people clambering for their piece of the pie, the dream of Western hedonism only a glimmer in your eye, served to you in endless media but unobtainable except through entrepreneurship. This splits the narrative into one that works just as well on either of two levels: you are both a character caught up in a specific and engaging tale of greed, power, and love, but you are also the continent writ small, a metaphor for the changing aspirations of an entire generation. Hamid’s prose is full of these double meanings, such as the following passage in which you are huddled around an old TV with your family: “When the show is done, credits roll. Your mother sees a meaningless stream of hieroglyphs. Your father and sister make out an occasional number, your brother that and the occasional word. For you alone does this part of the programming make sense. You understand it reveals who is responsible for what.” Your education has provided you with more than just the ability to read words; it has also allowed you to read between the lines, to realize who pulls the strings and who has their names on the checks.

You also read some interesting metafictional musings, moments when Hamid acknowledges the awkwardness of artifice and what it means to write or read, but you know that they’re unnecessary. This is one of those original works that are also resonant as a record of human experience and geopolitical shift, and a strong argument for Hamid as one of the most important writers working today. An enjoyable read no matter who “you” are.