Nothing could be less of a fantasy than the verdict announced in the Cannibal Cop case in Manhattan federal court on Tuesday morning.

“Guilty,” the jury foreman said. On all counts.

What had at least started as cyber fantasies of abducting, raping, torturing, killing, cooking and cannibalizing women had ended with 28-year-old New York City police officer Gilberto Valle facing a possible life in prison for conspiracy to kidnap.

He certainly could not argue that he had inadequate counsel. No defendant could have asked for more than defense attorney Julia Gatto’s impassioned summation. She had argued persuasively to the jury that the cyber chats the prosecution termed conspiracies were nothing more than disturbing fantasies, in numerous instances all but identical to other chats the FBI itself dismissed as make-believe.

Yes, Gatto said, Valle had looked up recipes for chloroform and named actual women as he spoke with fellow sickos on the Dark Fetish Network.

Yes, Gatto said, he had described acting out his dark imaginings in his basement or a house upstate.

Yes, Gatto said, Valle spoke of trussing his victims with rope and roasting them in an oven or on an outsized spit.

But, she noted, Valle had never actually made chloroform and he had neither a basement nor a house upstate. He also had neither an oven nor a spit with which he could cook even a petite woman. He had never bought so much as a yard of rope.

“It was all fantasy, sick, twisted, ugly fantasy,” Gatto told the jury.

And she reminded the jurors of something Valle had told a cyberpal, “I like to press the envelope, but no matter what I say, it is all fantasy.”

Yet, as convincing and compelling as she was, Gatto’s argument faltered for just the briefest of moments when she sought to explain why Valle had used the computer in his radio car to access a law-enforcement data base and run the names of several actual women. Valle, she told the jury, had only been checking the system.

“To make sure it’s working,” she said.

The explanation was so unconvincing that Gatto suddenly looked like exactly what she in fact was, a defense attorney seeking an acquittal. But the rest of her argument remained so convincing that prosecutor Randall Jackson seemed to be only flailing in his rebuttal.

Then he reminded the jury of Kristen Ponticelli. The 18-year old high school student had been the briefest of witnesses but also the most disturbing because she was so young, had no direct connection with Valle, and was so obviously unnerved by the thought that some stranger had marked her to be raped, cooked alive, and eaten. Another transformative moment came when the prosecutor projected on the monitors arrayed before the jurors the subject of a Google search that Valle had made.

“KRISTEN PONTICELLI ADDRESS.”

The two moments, one during the defense’s summation, the other during the prosecution’s rebuttal, left the jury with the question of why Valle would run a computer check or seek a teen’s address if he was engaged in nothing more than fantasy.

Even so, there had been no actual attempt to kidnap somebody. And none of Valle’s alleged co-conspirators had asked what happened to the plot when nothing came of it, a seemingly implicit acknowledgment that it was indeed fantasy.

“It’s a tough case,” a law-enforcement official said the day of the summations, when asked about the chances of a conviction.

The official said the government had wanted to extend the investigation before making an arrest with the hope that Valle would take more concrete steps toward making the virtual real. The FBI might even have employed an undercover as it does with online pedophile cases.

“The PD shut it down,” the official said.

He meant the NYPD, which understandably did not want an officer who harbored such fantasies walking around with a gun and handcuffs. What if he wanted a snack on the way home and accosted a woman on some pretext? Or what if he got involved in a contested shooting and it came out that he was a suspected cannibal?

The issue the jury now had to decide was where exactly in a shadowy blurring of the virtual and the real had Valle been when he was arrested. The defense had argued that the case was essentially a misunderstanding.

“The government simply doesn’t understand what fantasy role play is,” Gatto said during her summation.

But the defense itself had failed to adequately explain why such concrete acts as database checks could be just role playing—or why one of Valle’s online pals had asked for a reduced price or a payment plan when the cop offered to sell him a trussed-up woman to abuse and kill.

Nonetheless, the defense seemed more confident than not of an acquittal when a sealed note from the jury on Monday afternoon raised the possibility that it had reached a verdict. Valle was led in from a holding cell and his mother blew him two kisses from the spectator’s section.

Valle sat and Gatto patted his shoulder reassuringly, as she often had during the trial. She had become genuinely fond of her client.

“I like Gil,” she had said during one recess.

The note proved to be just a request to cease deliberations and head home at 4:30 p.m. Valle allowed himself a smile of nervous relief. Somebody joked that in knocking off early the jurors were proving to be Twelve Not So Angry Men and Women.

But apparently the jurors had simply decided to sleep on their decision. They had been back at their deliberations for less than two hours on Tuesday morning when they sent out another note, handwritten on lined paper.

“Your Honor, We have reached a verdict.”

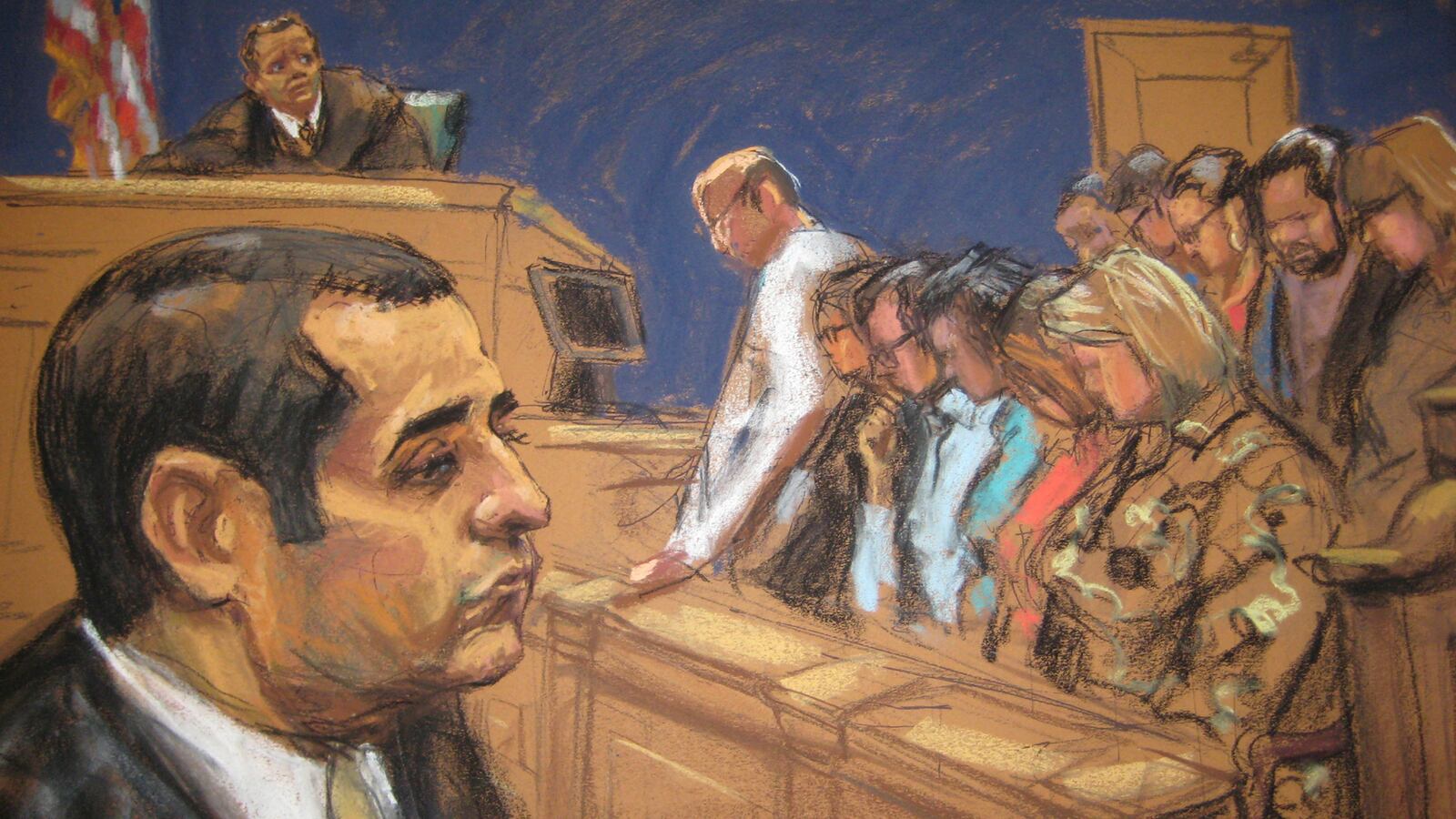

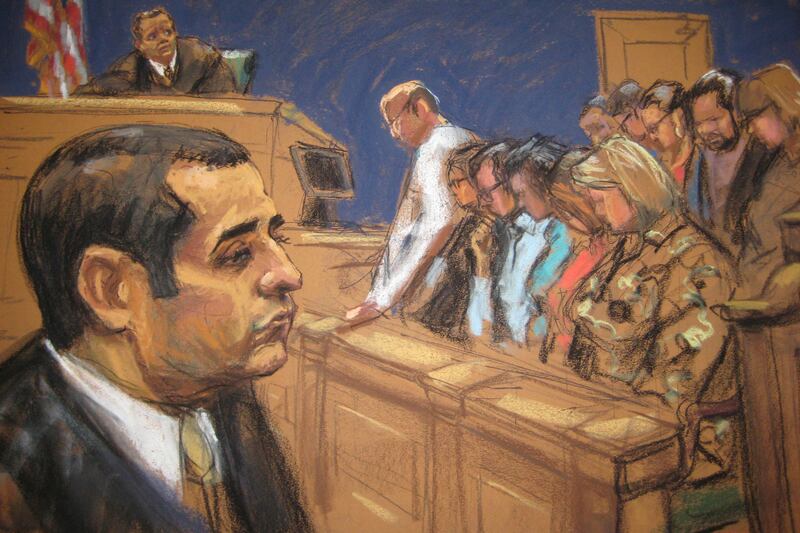

The clerk jotted down the time: 10:50 a.m. Valle was back at the defense table with Gatto when the jurors filed in. Valle’s hands were shaking as he faced the reality to which his fantasy had now led.

“Guilty,” the foreman said as to the conspiracy to kidnap charge.

The foreman repeated the word regarding a second charge, accessing a government data base. Gatto slumped forward, but recovered herself. She embraced her client before he was escorted away.

“This was a thought prosecution,” she said afterward.

She suggested that the jurors had simply been unable to get past the ugliness of those thoughts and she pledged to appeal. Many observers support her contention that people should not be prosecuted for fantasies, however repulsive. The verdict caused Valle’s mother to repeat something that others had exclaimed upon seeing her son’s online imaginings.

“I’m shocked, I’m shocked, I’m shocked,” she said.

The problem Valle will face when appealing the conviction is that to be guilty of conspiracy under federal law you need only discuss plans to commit a crime with another person and take just one concrete step toward making them real. The step can be so small as running women’s names on a database or looking up a teen’s address.

“We did what we had to do,” the foreman said after the jury was excused.

The fantasy photos of women being roasted alive may have reinforced the jury’s belief that it had indeed done what was necessary, but there was another photo that could only have made the jurors wish it had been otherwise. This one shows Police Officer Gilberto Valle in his police uniform, holding his baby daughter.