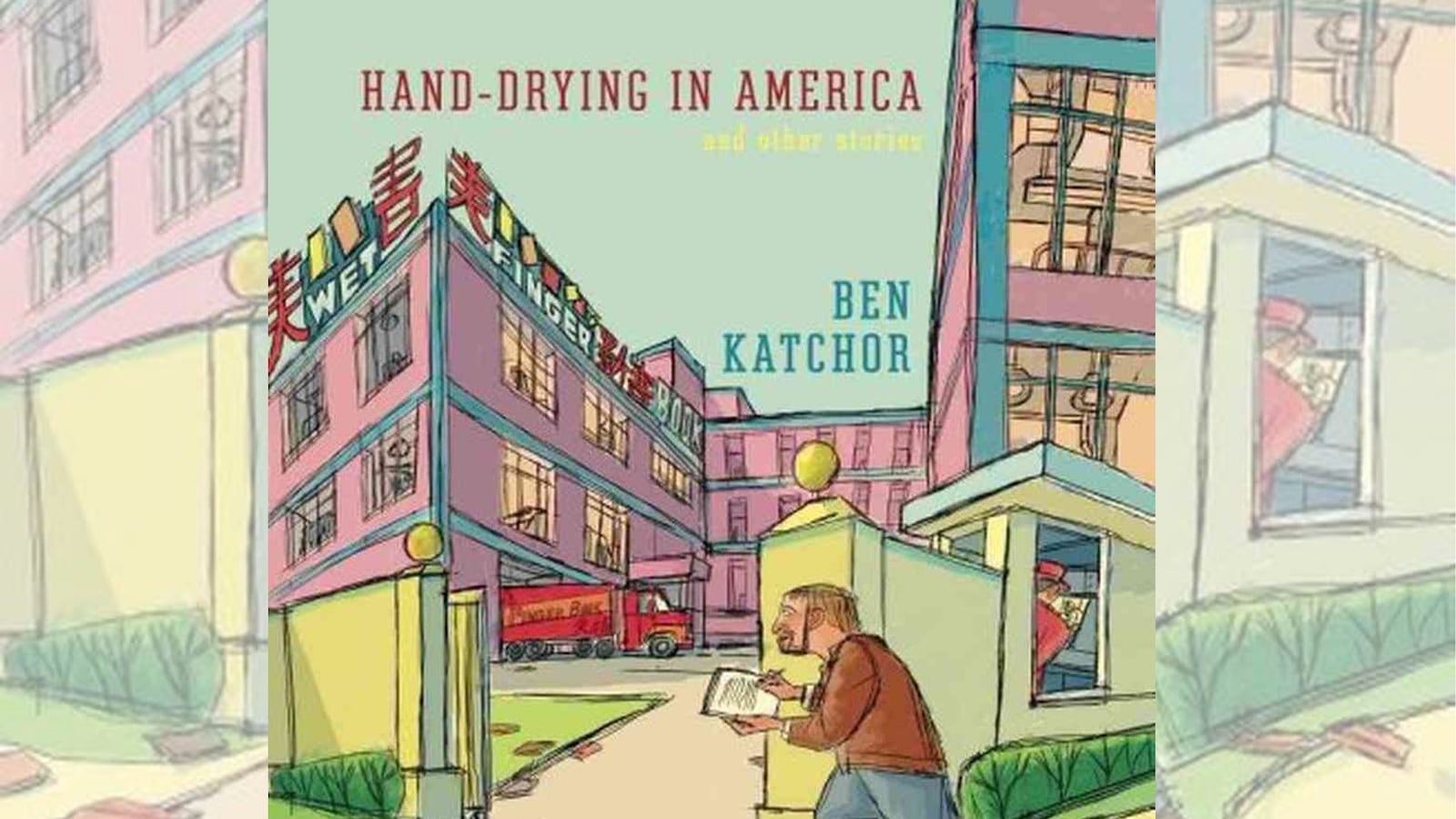

Like all New Yorkers, Ben Katchor is obsessed with real estate. The characters of his imagined Gotham don’t pine for spacious lofts in SoHo or the grandeur of The Dakota; their mania is for obscure but resonant architectural detail—doorknobs, tissue dispensers, and cornices rule their minds. The distortion—bending familiar scenes away from the expected totems of modern living and toward seemingly trivial details—gives us a satire that illuminates as much as it skewers. At his best, Katchor creates a lucid derangement of the ordinary, revealing the power of all the cluttering artifacts that surround us but go unnoticed. His new collection of comic strips, Hand-Drying In America, is a dark, funny, and compelling experience, as engrossing to view as it is to read.

There is an implicit critique of capitalism in Katchor’s comics. They are far from overtly political, but the theme of people being unthinkingly ruled by the objects they are sold and the structures built to contain them is inescapable. The 159 strips collected here first ran from 2008 to 2012 on the back page of Metropolis, an architecture and design magazine. The ideas in these comics are more subtle and incisive than simply depicting the imprisonment of the capitalist metropolis. Anxiety produces characters who gripe about being constrained and inconvenienced by the world. But it also gives us people who express those feelings through a neurotic lust for objects.

Architects are frequent characters in these pages, but they are as confused and misdirected as everyone else. Most often the architects are comic foils, setting their ambitious designs loose, only to be undermined by a public that improvises unexpected uses. In “The Unmarked Pipe” an importer of wet walnuts finds a strange pipe running through the new office that he has rented on Maskilim Avenue. The man, gripped by curiosity, drills a hole to discover what the pipe carries. A white burst of compressed air shoots out and knocks him down. The gas was in fact piped to local ice cream parlors that drew their whipped cream from a central reservoir, and they suddenly found their dispensers losing pressure. The comedy of the piece doesn’t mask the grimness of its premise: The price of looking too deeply into the wiring of the modern machine may be getting knocked on your ass and going without ice cream.

Katchor’s one-page compositions have their own architectural quality, arranging blocks of image and text to create foreground and background, close-ups and vistas. In a typical comic the panels are arrayed around one double-sized center frame—often a rendering of a building or a dense city block. In the style of tentative sketchbook drawings Katchor adds overlapping lines to articulate a single feature, giving a disheveled quality to his characters and a blurred dreamy aspect to his buildings. The crossed and doubled lines seem to fray the boundaries and details of his figures, and give the images a nervous energy in tune with the apprehensions and sudden panics of the people he depicts. The heads are the only large aspects of these characters; no one appears tall or lanky. These are men and women who hunch as if compressed by their own tension. But atop the squat bodies the heads are large and the faces like masks, their most common expression a grimace, which appears more natural and less disturbing than when they exhibit rare smiles. There is something imposing and demanding in the myopic claims of these characters. Though they look like little potsers and nudniks—wise men of Chelm—they are made vibrant by the ardor of their claims. The pages are drawn in a grayscale that is rich enough in its contrasts to suggest both color and light but suffuses the work with a bleakness that is only occasionally relieved by its humor.

Comparisons to Chris Ware, the other great comics artist who deals with urban structures and the enervating enclosure of modern living, seem obvious. Both specialize in architectural rendering and characters that are ill at ease within their cities. But against Ware’s exploration of the sterile and alienating quality of modern technologies Katchor’s work has a pungency and strange sexual energy applied to the appliances of the late 20th century.

Then there is the quality of Katchor’s humor, a smoked fish surrealism that gives a vaudevillian undercurrent to even his bleakest stories. Just consider the occupations and names of people and places: Saltine Avenue; a cracked cup inspector from the city’s health department combing lunch counters for chipped mugs; de-consecration specialists; the Vagus River; young men who accompany diners into restaurants to do the work of opening all of their condiment packages for a small fee; the Vishnu-Schist apartment complex; an undercover psychiatric social worker who prowls the streets and stalks people through public spaces and into their own homes looking for the maladjusted individuals who might be convinced that they need her help. All of these characters are strange and familiar, distorted reflections of our own everyday inconveniences and pre-occupations. They each isolate some locus of modern existence where the large structures of capitalism and culture intersect with the mundane and live out their dramas in those absurd junctures.

While most of the comics in this collection seem focused on the pre-digital objects of consumer culture, there are occasional appearances by truly contemporary phenomena like email. But even when typing at a keyboard, the characters are committed to an older world, still confused and unable to catch up to the latest round of disorienting technologies. If Katchor sets a scene in front of a computer, expect to see sardine oil smudged across the screen. It’s in the pre-digital objects of late capitalist culture where our modern condition is most rooted and searched. He locates and analyzes our psychology in the ubiquitous appliances that mediate the experience of our daily lives.

Katchor trains his eye on everything we fail to notice, the details that are traditionally only props in the background, not fitting subjects for art. But Katchor’s art is to take the human endeavor seriously by examining our interactions with something as mundane as a hand-drying machine. The pathos is in the appliances and the props become the subjects that reveal us to ourselves.