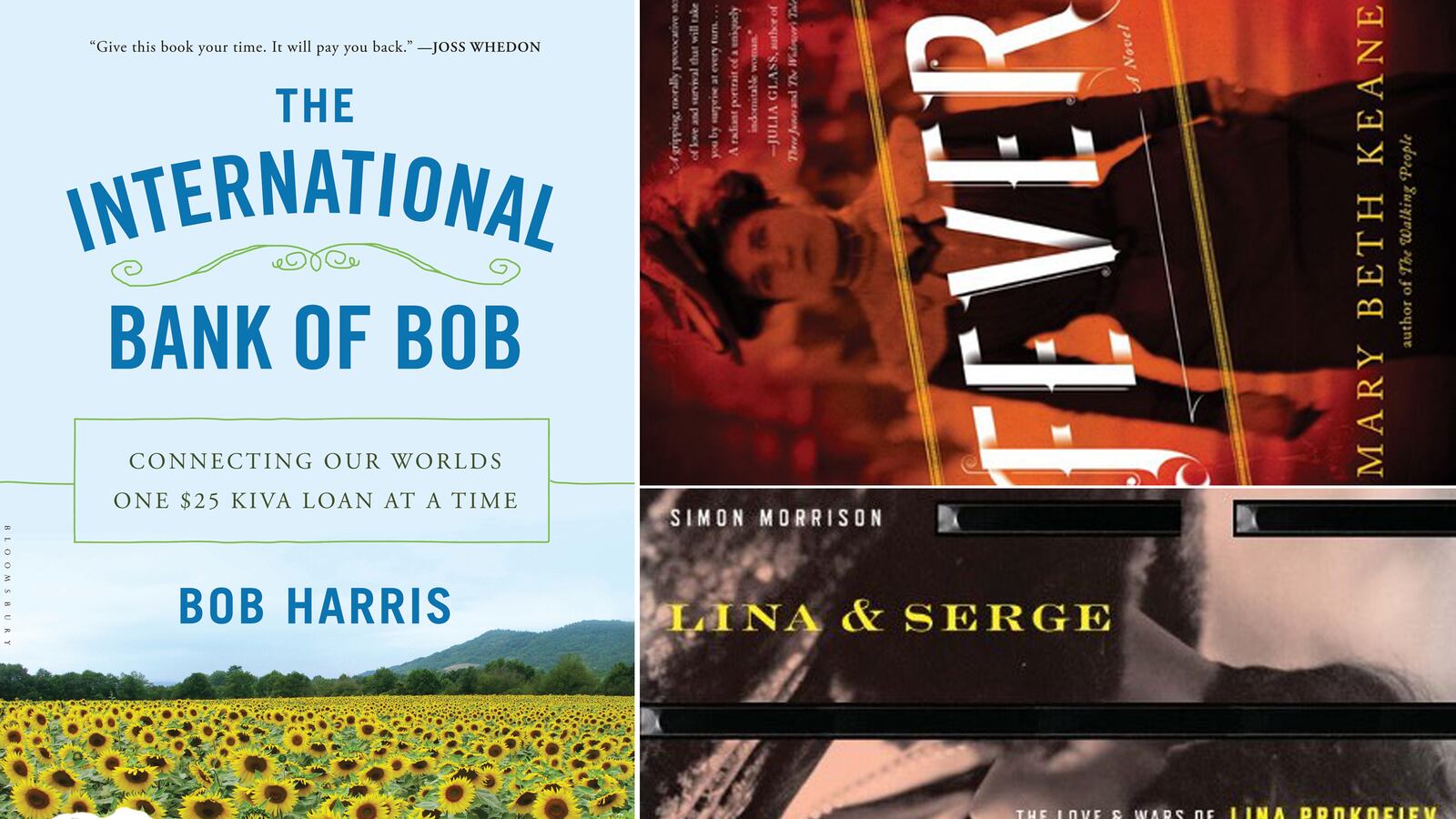

Lina and Serge By Simon Morrison

The remarkable story of the wife of composer Serge Prokofiev, who was imprisoned in the gulag for eight years.

Carolina Codina, whose stage name was Lina Llubera, was born in Madrid, raised in Brooklyn, and dreamed of being an opera singer admired by the world. Instead, she married Serge Prokofiev, who was one of the most admired composers on the world stage, and in 1936, Stalin’s Soviet Union lured them back to Moscow. What happened to Lina is heartbreaking: Prokofiev fell in love with a much younger woman and left Lina during WWII, and, trapped in Soviet Russia, in 1948 she was shipped to the gulag for trying to obtain an exit visa. She endured eight long years in prison. Although her story is extraordinary, it is also representative of an entire dark age in Russian totalitarianism. “The pledge that the Soviet Union made to Lina—of material comfort and social status, of a cosmopolitan life secured by the social state, of individual freedom and special privilege—mirror those it made to itself, its citizens, and its sympathizers,” writes Morrison, a music history professor at Princeton and one of the world’s leading authorities on Prokofiev’s compositions. “Lina never came to terms with the tragedy of her life, nor did the country that was its stage for many years.” She persevered, and finally escaped overseas in 1974. She died in 1989, unable to witness the fall of the Soviet regime.—Jimmy So

The Blue Book By A.L. Kennedy

A love triangle set on an ocean liner that comes together beautifully.

A blue book—not to be confused with the yellow pages, a white paper, a green paper, or a black book—is a compilation of information like an almanac, or in the legal world it is the style guide for its citation system. Kennedy’s new book often does not read like a conventional novel, but more like Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, a compilation of exquisite sentences and conversations that play with narrative and continuity. The novel weaves together a lot of characters, at the center of which is a love triangle: Elizabeth and Derek, a British couple traveling on an ocean liner; while on their transatlantic trip they run into Arthur, Elizabeth’s ex—the two of them used to work together as spiritual mediums, pretending to contact the dead relatives of their customers. A lot of lies were told back then, but in the trapped, almost existential world of the cruise ship, truths emerge and float to the surface like individual bubbles of information. Only by the end do you see the big picture—a system of parts that come together as a beautiful book, floating in the blue ocean.—JS

The Faithful Executioner By Joel F. Harrington

What exactly was life like as a 16th-century executioner? A journal reveals all.

Apprenticed at a young age into the family business of executions, Frantz Schmidt is unique among his peers for a simple reason: he kept a journal of his work—a journal that Joel F. Harrington brings to life in his new book, The Faithful Executioner. Harrington’s history is telling not just about the executioner’s ordeals, but also about the state of the society in which he wielded his blade. Schmidt inhabited an imbalanced social structure where famine, poverty, and disease drove common people to steal and mercenaries to pillage. In this world the executioner’s sword was the only true justice to be found. The premise of Harrington’s book appeals to a certain voyeuristic interest in the mind of a killer—the same interest that sells true-crime thrillers by the thousands. But state-sanctioned executioner is rarely the subject of close examination, and in any case modern-day executioners rarely get so up-close and personal with their charges as a 16th-century ax man. The journal, of course, is spotty, and offers little of Schmidt’s life outside of his work. Therefore Harrington is necessarily tasked with filling in a lot of blanks, and with research presents a much sharper image of the executioner. The resulting text is both social commentary and annotated memoir—equal parts enlightening and enjoyable but sharp throughout.—G. Clay Whittaker

Fever By Mary Beth Keane

The life and times of an asymptomatic typhoid carrier in early 20th- century New York.

Mary Mallon has an understandable reaction when she receives news that she is carrying typhoid fever. The first reaction is confusion, as she has no symptoms. The second reaction is denial. How could she be the cause of dozens of deaths throughout her career as a cook, silently and unknowingly killing just by doing what she loves to do? An asymptomatic carrier, Mary Mallon spent nearly 20 years working as a cook for the well-to-do families of turn-of-the-century New York City, until a sanitation engineer traced a deadly pattern back to her employment history. Faced with responsibility for all those deaths, headstrong Mary’s common-sense approach to understanding and dealing with her situation tells her that she can’t possibly be the cause of so much destruction, and that the idea of someone sick without symptoms is ridiculous. The justice-for-all voice in her head tells her that continuing to cook after doctors have told her never to do so again means she is overcoming adversity, not dooming her employers and their families to death. Out of this conflict, Keane builds a sympathetic character, her ironic disconnect reminding us constantly of the tragic nature of Mary’s condition. The result is that, while we occasionally forget that Mary’s disease is inherently linked with her fate, we never lose sight of her as an afflicted individual.—GCW

The International Bank of Bob By Bob Harris

One man’s journey through a world helped by generous microloans.

Bob Harris is a writer turned investor whose projects and investments reach from Chicago to Kathmandu. But it’s not really investing in any contemporary sense. Harris isn’t out to make money or top up his 401(k). He’s not trading on oil futures so much as he’s trading in futures through Kiva.org. Kiva is a nonprofit microfinance organization that allows users to loan money worldwide. Today they have more than 900,000 lenders and more than $400 million lent in 67 countries. With a matter-of-fact tone, Harris tells the story of his journey around the world, visiting the people and places where his money has made some impact and seeing firsthand the daily lives of the people who didn’t win the birthright lottery and end up in a developed, wealthy country with tons of opportunities (like himself). Harris’s sparks of interest in these causes come from familiarity; he sees his mother in the smile of a farmer, small families trying to make something of lives in remote and impoverished corners of the world. The result of his writing is a series of honest portraits of mothers, husbands, and farmers to whom a $25 loan was life changing. Harris, in this journey of discovery, is forced to come to terms with a lot of sad facts, namely that the world is still full of poverty, and that a few microloans well applied can’t protect everyone from poverty. But Harris also finds hope even in the worst of these places, with a hug from a couple of kids or a little progress here and there. His hope becomes ours as well, and with the idea simmering, typing “kiva.org” into a Web browser seems awfully easy.—GCW