The Curiosity rover is very well named. There is little doubt that, as Fox Mulder said on The X-Files, “we want to believe.” Being alone in a vast universe is a terrifying prospect, and so the hope that we will discover life elsewhere in the universe waxes eternal.

Happily, hope is not all there is. We are sending out increasingly sophisticated probes to look for life in, what we hope at least, are all the right places. And at each step we are getting results that encourage us to keep looking.

A few weeks ago, a team at Berkeley announced that conditions on comets are sufficient to allow the creation of complex dipeptides, linked groups of amino acids, which could have provided the seeds of life on Earth.

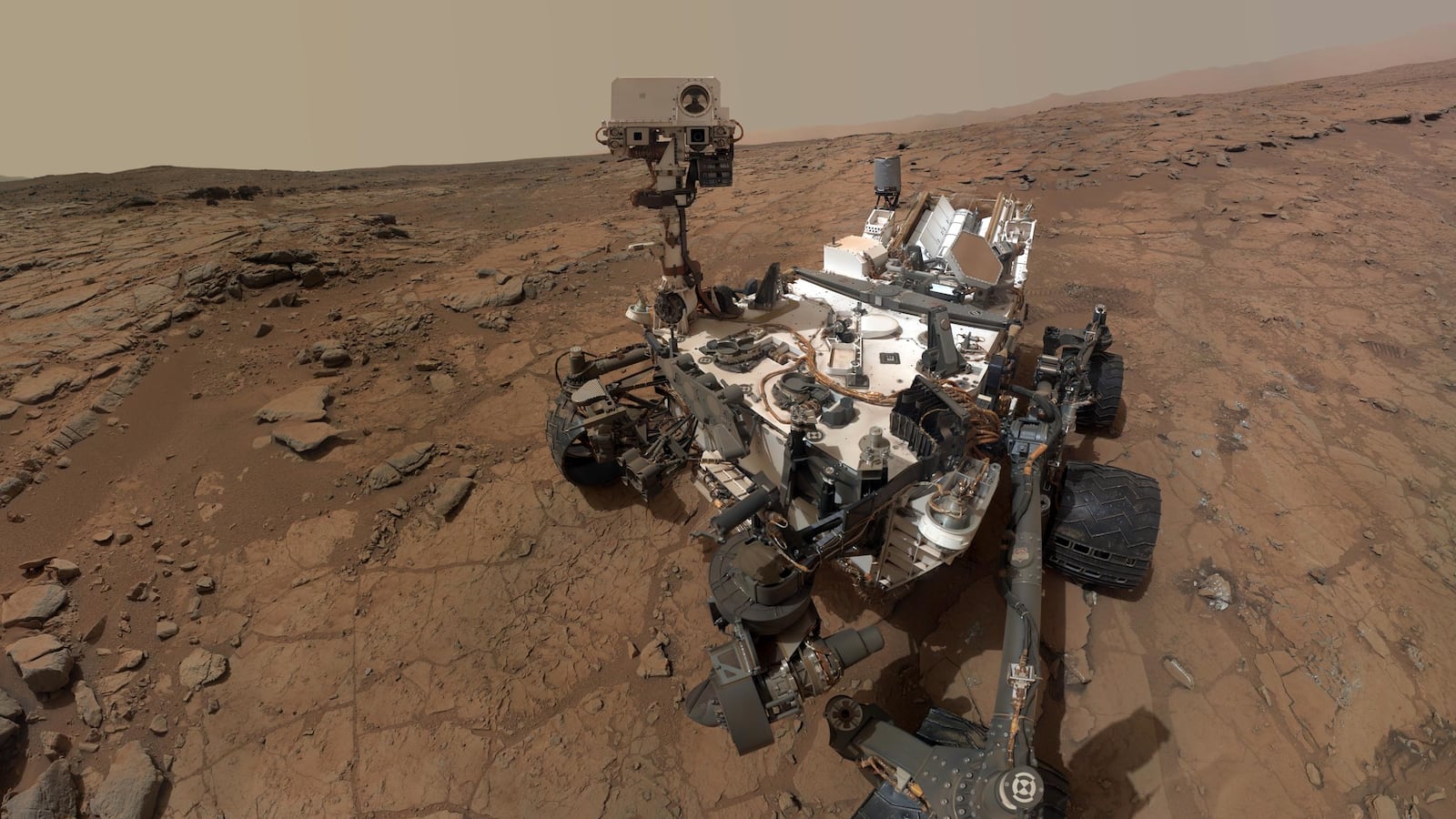

Last week NASA announced a new discovery by the Curiosity rover that increased the likelihood that we may have had cousins on Mars.

The rover had previously discovered definitive evidence of running water in the relatively recent past. Since water seems to be one of the prerequisites for life as we know it, that was an encouraging sign. Then, when the rover drilled into a rock in one of those ancient streambeds, it discovered elements—including sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and carbon—that could have provided nutrients for biological processes.

But even more interesting, I think, was the fact that the clay discovered in the drill sample was gray, rather than red.

Life on Earth was possible, surprisingly perhaps, because no free oxygen existed on the planet for the first billion years or so. All the oxygen in the current atmosphere was created by living systems.

You see, oxygen is essentially a poison. Organic materials that get exposed to oxygen get oxidized, and in the process give up the stored energy they might later use to power life, in a slow version of what happens when you light a match.

When it becomes oxidized, iron rusts—and turns red. The discovery that not all the surface materials on the red planet are oxidized, suggesting the early wet environment was not oxidizing and that it was not entirely acidic, means that early life could have exploited the energy latent in nonoxidized material to power its metabolism.

None of these results, of course, gives direct evidence that Mars actually ever harbored life. But it does give increased reason for hope.

If we do eventually find evidence for life on Mars, extant or extinct, the big question will be whether it evolved independently, or whether we will have just discovered evidence of distant cousins. Material routinely travels between Earth and Mars, and microbes could easily survive the voyage.

For me, however, that provides an even more enjoyable, although unlikely possibility. Perhaps life first originated on Mars and then was transported to Earth? In that case, if you want to see a Martian, just look in the mirror.

Lawrence M. Krauss is Director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University. His most recent book is A Universe from Nothing.