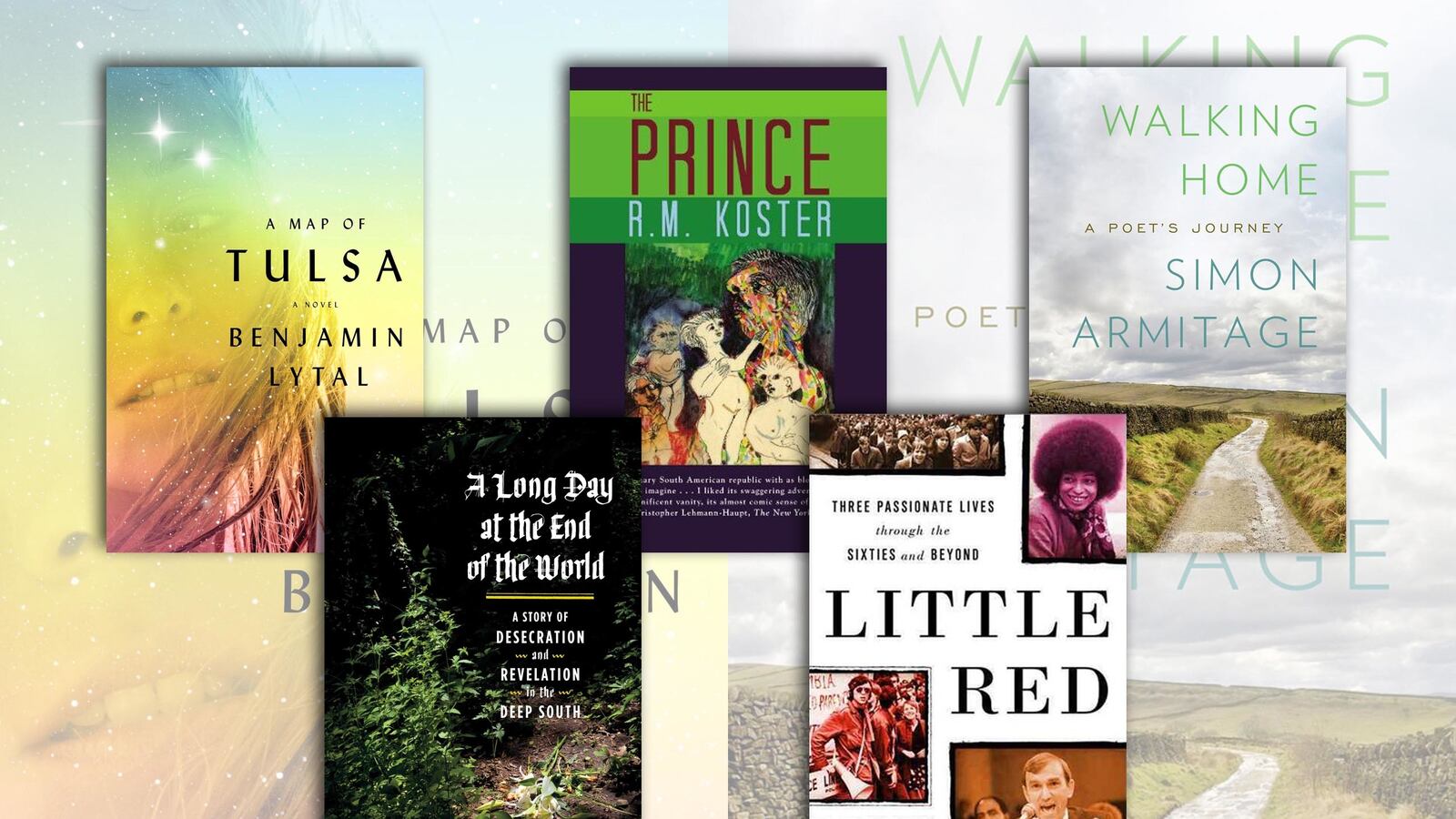

The PrinceBy R.M. KosterA reprint of a 1972 classic in which a fictional Latin American nation boils in violence.

The value of a well-chosen reprint should go beyond merely reminding us of a good book that we might have forgotten—it should reengage us with a former state of the world and that world’s reflection in literature. The Prince, R.M. Koster’s 1972 National Book Award–nominated first installment in the Tinieblas trilogy, is the story of Tinieblas, a fictional Latin American country based on Koster’s time spent deployed as a soldier in Panama, and one of its many would-be rulers, Enrique “Kiki” Secundo. Kiki narrates his autobiography and revenge fantasy from the state of near paralysis he was left in by an assassination attempt on the cusp of his ascendancy. It may be odd to call extreme violence in literary fiction “refreshing,” but reading The Prince reminds us of its notable absence in much of today’s work. The book opens with Kiki’s graphic imagining of how he will torture his assassin when he finds him and soon moves on to a historical lesson on one of Tinieblas’s former leaders, who had a fondness for stringing people up to crosses set out in the tide and watching them be eaten by sharks (until, of course, the people decide that it’s his turn). The book is an older cousin to Robert Stone’s A Flag for Sunrise, not only for its imagined Latin American state, but also in the way that Koster blends political turmoil with personal unrest.

A Map of Tulsaby Benjamin LytalA young man returns home from his first year of college and enters an unlikely love affair that changes him forever.

The story of a homecoming is one of the oldest archetypes in the cultural record, but usually the hero must undergo a difficult odyssey before he makes it back to his front porch. In this debut novel from former New Yorker staffer Benjamin Lytal, Jim Praley returns to his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, after the not particularly trying experience of his freshman year of college on the East Coast. But he has allowed his poetic aspirations to grow just large enough for him to be frustrated, and he’s seen just enough of the world to feel washed out and numb upon reencountering his stomping grounds. “I came back to Tulsa that summer ... to prove that it was empty,” Lytal writes, “and in hopes that it was not.” When he meets Adrienne Booker, a high school dropout with family oil money and a penthouse downtown, the two engage in a love story that we may have seen before, with Jim as the “magnificently hollow” boy looking to kick-start some kind of rebirth and Adrienne as the expansive spirit drawn to this blank slate, at one point using his bare chest as a canvas for her art. But when the narrative jumps ahead five years, the true apocalyptic shape of the novel begins to pay off. Lytal commands a shadows-on-the-cave-wall symbolism reminiscent of Donald Antrim, and never before has the city of Tulsa been given such resonant characterization.

Walking HomeBy Simon ArmitageThe power of poetry alone fuels Simon Armitage on his epic walk along the Pennine Way.

If a sensitive American soul is looking to test itself or come to know itself more deeply, it will commonly embark on a cross-country drive. In the U.K., where distances are more manageable, it’s more likely for one to go for a stroll, like the titular character of last year’s Booker Prize nominee The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. In Walking Home, poet Simon Armitage tells the story of his attempt to walk the Pennine Way, a national trail that runs the length of the country down the middle. A difficult feat, to be sure, but not entirely unusual for adventuresome Englishmen and -women. What makes Armitage’s pilgrimage special is that he attempts to fuel it on poetry alone; each night, in various small towns along the way, he gives a poetry reading and passes a hat (actually, a hiking sock) so people can give monetary expression to the value of his words. Although Armitage is a poet, he does not dally long on the twisting of a leaf upon a dying branch or other poetical distractions; this is an adventure story, compellingly and humorously told, British upper lip remaining stiff in the face of hardship, defeat, and the occasional triumph.

A Long Day at the End of the WorldBy Brent HendricksA poet’s journey to redeem the criminal mistreatment of his father’s remains and his relationship with the South itself.

The reader may recall a particularly macabre news item from back in 2002, when it came to light that the operator of the Tri-State Crematory in Walker County, Georgia, had committed an appalling crime: rather than properly cremate the remains that were brought in to him, he had stashed over 300 bodies in various places on the crematory’s grounds and returned to the grieving families nothing more than containers of concrete dust. Among the desecrated bodies was the father of Brent Hendricks, a poet whose propensity for misfortune (or “visits from the Shit Fairy,” in his family’s parlance) is matched only by the lyricism with which he can strum the misfortune’s reverberations. A Long Day at the End of the World is the story of Hendricks’s physical pilgrimage to the site that hid his father’s body and his concurrent attempt at emotional reconciliation with both his family history and the fabric of the South itself. Hendricks compares his dark journey, a true Southern Gothic in more ways than one, with the wanderings of explorer Hernando de Soto, who trod the same turf centuries before—both adventures equally grim, and both equally intertwined with one of America’s most haunted hinterlands.

Little Red by Dina Hampton A story of the ’60s and beyond as told through the lives of three classmates at a Greenwich Village school.

Hidden in one of the magical recesses of New York City’s Greenwich Village is the Little Red School House, known as Little Red to alumni and as a beacon of progressivism to others in the know. Since its founding in the ’20s, the school has been dedicated to its alternate vision of social justice; field trips for students might have included meetings with striking workers at the Phelps Dodge plant in Queens or picking cranberries with migrant workers in the bogs of New Jersey. In Little Red, Dina Hampton traces three lives that all began at Little Red before diverging wildly: Angela Davis, at one time the face of the Black Power movement; Tom Hurwitz, an SDS member turned award-winning filmmaker; and Elliot Abrams, a key neoconservative who has had the ear of both presidents Regan and George W. Bush. This is not just another tie-dyed cultural history of the ’60s, but rather a thoroughly researched three-part biography that divides the era into a triptych. Hampton shows how America still has a long way to go before we’re out of the shadow of that decade, for better or for worse.