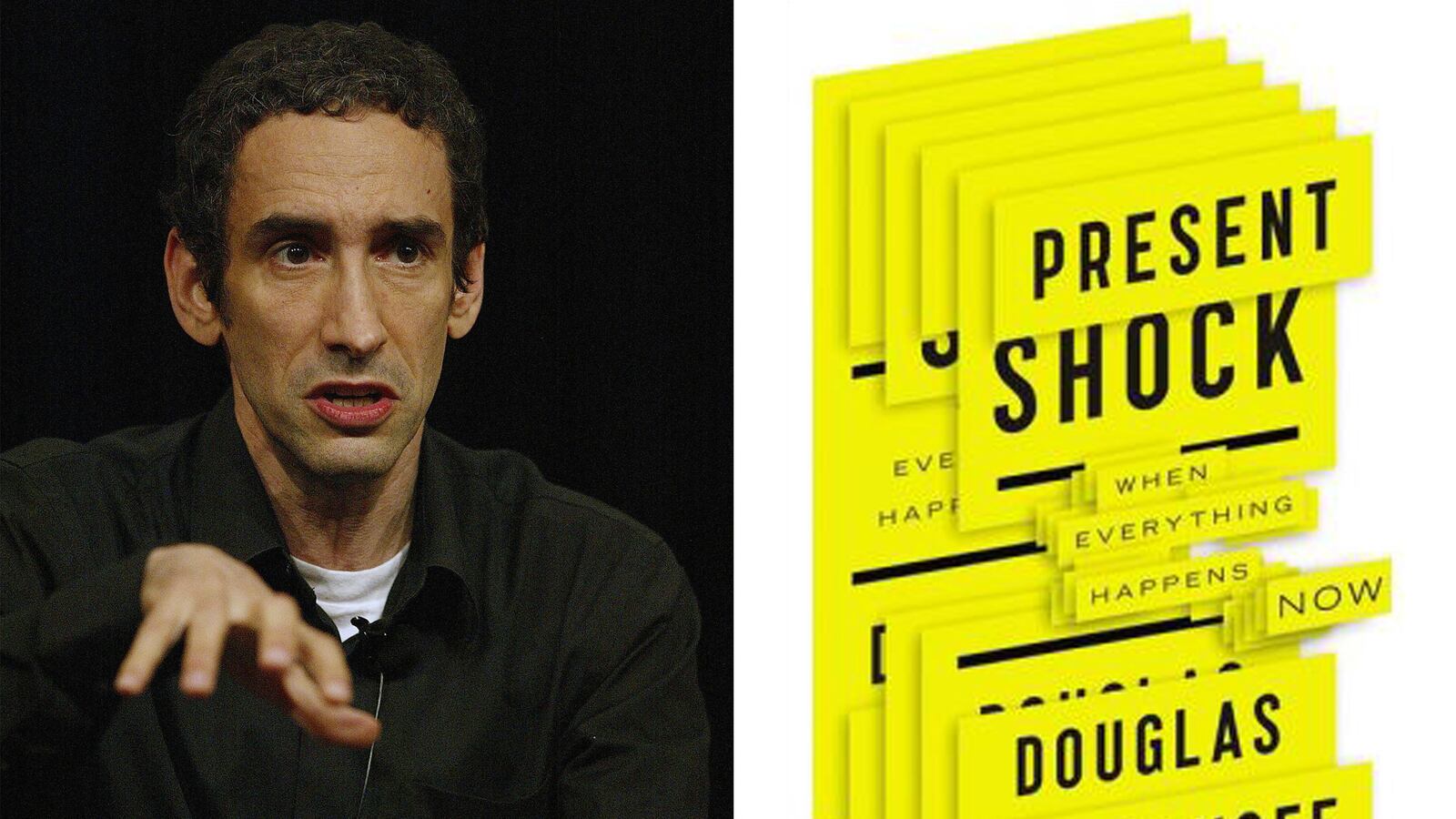

In his new book, Present Shock, the media theorist Douglas Rushkoff takes a stab at describing an emergent cultural phenomenon. According to his subtitle, everything happens now, and that’s problematic, leaving us marooned in a timeless space, struggling with endless streams of sensory input, the collapse of narrative, and an inability to cope with the speed and asymmetrical power of digital media. Whereas corporations, for example, once put products out in the world and waited for a response, they’re now overpowered by instantaneous feedback loops, by the immediate, perfervid response of social media, which prevents them from observing patterns and making long-term plans.

It’s easy to recognize some of the qualities of the world that is presented by Rushkoff. Yet he fails the distinction test; much of what Rushkoff describes is either not very new or not connected in the ways he claims. Instead, Rushkoff has created an elaborate system of meaning, one built on unwieldy neologisms, peculiar readings of popular culture, and a tendency toward abstraction. There’s some meta-irony here since Rushkoff fails to create a convincing narrative about the end of narrative itself, and despite his warnings about searching for patterns when surrounded by so much feedback and noise, he doesn’t connect his own data points into a persuasive model.

Rushkoff’s title is a riff on Future Shock, the 1970 bestseller in which futurist Alvin Toffler described a society overwhelmed by “too much change in too short a time.” Toffler’s thesis hasn’t aged well—and has long had its critics—but it drew on some notable ideas of the time, such as the concept of “information overload.” It was the dawn of mass media and the golden age of disaster movies; U.S. soldiers were dying en masse in Vietnam as Nixon skulked through the White House; a bestselling book, The Population Bomb, had predicted an impending mass starvation due to overpopulation; science fiction’s utopian visions had moldered into something darker; the Cold War was stagnating, as the economy would later in the decade. There were reasons, in other words, to worry about the pace of change and our ability to keep up.

Rushkoff, on the other hand, is worried about five main concepts, which also happen to be the book’s chapters: narrative collapse, digiphrenia, overwinding, fractalnoia, and apocalypto. Some of these are more vaguely defined than others, but that is also a key to this book’s method. These terms are both cumbersome and strangely mutable. For example, “overwinding” is the “effort to squish really big timescales into much smaller or nonexistent ones”; but it’s contrasted with “spring-loading,” which allows us, by way of preparation, to pack a lot into a single event or action (such as a “pop-up” hospital deployed to disaster zone).

In the first chapter, “Narrative Collapse,” Rushkoff’s thesis already falters. Where he sees lack of narrative, I find the opposite—narrative in all its multivalent forms. As an example, he offers the Baltimore crime series The Wire as an emblem of present-shock narrative, “a static world that can’t be altered by any hero or any plot point. It just is.” I disagree. Along with season-long narrative arcs, the show displays all of narrative’s constituent parts—plot, story, change over time, character development, a sense of forward momentum. Yes, the characters are mostly victims and failed reformers of the institutions (police force, schools, city politics) they operate within, but their narrative draws more from the realm of Greek tragedy than digital-age paralysis.

About The Simpsons, Rushkoff says that though “the episodes have stories, these never seem to be the point,” and that Family Guy uses pop-culture references to “escape from the temporal reality of the show altogether.” On these shows, characters may die and towns may be destroyed, but the status quo always returns.

Rushkoff may just be looking for the term postmodernism, which isn’t so much the decline of narrative as the breakdown of traditional types—all those sturdy, monolithic modernist narratives. Instead, we have irony, allusion, meta commentary, fragmentation, parody, and pastiche. On television, stories may be told elliptically, but sitcoms still have their A and B plots. Community, then, doesn’t reflect some narrative fragmentation, as Rushkoff claims, but in rather standard postmodern style deconstructs sitcom tropes while ironically reenacting them, creating a burlesque.

Rushkoff also makes the mistake of considering reality TV “unscripted.” These shows are essentially scripted—through savvy editing, the manipulation of contestants, and even written dialogue (look for the title “story editor” in a show’s credits). So many of these shows share the same devices that we’ve come to expect specific narratives from them, such as the regular appearance of a semi-closeted Real World cast member who comes out to a homophobic Southern castmate. This is not a breakdown of narrative but its standardization across media.

Rushkoff’s treatment of how history has been altered by present shock is also problematic.

Rushkoff offers the anecdote of Eisenhower’s secretary of state John Foster Dulles flying to Egypt to negotiate the Aswan Dam treaty “back in the 1950s” (note the hazy dateline). He claims that Dulles botched the negotiations because he was groggy from jet lag—a little understood concept then. “The U.S.S.R. won the contract,” Rushkoff writes, “and many still blame this one episode of jet lag for provoking the Cold War.” This is one of those ultimately useless morsels of historical causality, akin to Pascal’s notion that if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter, “the whole face of the world would have been changed.” Even if one accepts Dulles’s oft-cited deathbed remark—that jet lag did hinder him—the Cold War was well underway by 1956, the year that the Aswan Dam negotiations broke down.

Rushkoff claims that digital media upsets our relationship with time. Computers do everything at once, while humans are dependent on temporality and our biological clocks; the clash of these two forces is one aspect of “digiphrenia.” Rushkoff critiques Nick Denton’s Gawker media empire, where, he says, writers are subjected to constant pressure to be always on and connected because they must post 12 times per day. Gawker, in essence, is guilty of being a digiphrenic work environment. But Rushkoff is drawing from Vanessa Grigoriadis’s 2007 New York magazine story. As has been widely chronicled, Gawker is a far different workplace now, with most employees salaried, receiving benefits, and freed from traffic benchmarks. Rushkoff seems here to be looking for the minority report, the one interpretation that satisfies his model. It’s a recurrent problem in Present Shock.

Rushkoff, not done with reality TV yet, argues that explosive fights on the Real Housewives shows can be attributed to plastic surgery. The women, with their frozen faces, can’t express traditional body language and “send each other false signals,” leading to constant feuding. They are aspiring for youth, trapped in “the short forever.” But a far more prosaic explanation for this behavior goes unmentioned—namely that these shows exist mostly to have their stars fight, and that these women are almost certainly pushed to act out such drama. (They also know that conflict is more likely to get them on the homepage of TMZ.)

By the end of the book, we have arrived at apocalypto. The term refers to “a belief in the imminent shift of humanity into an unrecognizably different form.” Rushkoff surveys some apocalyptic fantasies—including zombies and the prepper movement, which believes that doomsday approaches—along with strains of eschatology and the singularity. But why invent the concept of “apocalypto” at all, when he could instead draw on a rich literature about millenarianism, utopian prophecy, Armageddon, and so on? Is this really a new phenomenon?

The same question could be asked of other parts of Present Shock. If Rushkoff has gone through the trouble to theorize overwinding, with its emphasis on time and labor, why does he pay so little attention to the very ideas that could support his concept—Marxism’s theory of labor value, labor rights and worker productivity, the relationship between planned obsolescence and consumerism? If he’s writing about digiphrenia, why is there nothing about technological anxiety or similar concerns about the introduction of anything from the steam locomotive to television?

Rushkoff himself inadvertently provides the answers, when he remarks that futurists always have an agenda, no matter how well intentioned they are. That’s because their stories are “tailor-made for corporations looking for visions of tomorrow that included the perpetuation of corporate power,” he writes. “Futurism became less about predicting the future than pandering to those who sought to maintain an expired past.”

In this environment, companies hire consultants to “give them ‘mile-high views’ on their industries.” Rushkoff himself is one of those consultants, and in the book he describes his meeting with an unnamed CEO after some disastrous tweet. “In less than 140 characters,” Rushkoff writes, “a well-followed Tweeter was able to foist an attack on a corporation as disproportional and devastating as crashing a hijacked plane into an office tower.” The details of the scandal are not important, he claims, to which I could only respond, in the margins of my copy of the book, with scrawled exclamation points of disbelief. Why aren’t the details important? Should I be offended at the comparison of a tweet to a terrorist attack, or just confused?

Rushkoff doesn’t seem to realize that much of his book resembles those futurists’ mile-high visions: breezily reductive, shaky in its history, loaded with jargon like “pure time compression” and “temporally compressed lending instruments.” The value of these terms lies in their baroqueness, in the way they pile up upon each other like garish baubles. But I suspect that their full meaning will be unfolded by way of a PowerPoint presentation, delivered for a five-figure fee in a corporate boardroom near you.