The cover is green linen with the title printed in forest green letters, A Field Guide to Western Birds. An imprint of a swift appears as the heart of the book. The backside of the book offers a seven-inch ruler to gauge the size of any bird viewed. Roger Tory Peterson is the author and illustrator who has made his signature field guides not only bibles to amateur naturalists but iconic.

I have my grandmother’s field guide in hand and open the book. The end sheets are a display of silhouettes: roadside birds on the front; shorebirds on the back. My grandmother has identified each silhouette by name with her red pen. No. 1 is mourning dove, No. 2 is house sparrow, No. 3 is bluebird and so on. Her identification continues on the back beginning with No. 1 as Forster’s tern and ending with No. 24 as green heron.

This particular Field Guide to Western Birds, published in 1941 by Houghton Mifflin, bears two signatures: Kathryn Blackett Tempest, the owner, and Roger Tory Peterson, the author. He offered one additional word, “Joy,” which is what birdwatching is, truly.

“This book was designed so that live birds could be run down by their field marks without resorting to the anatomical differences and measurements that the old-time collectors used. Key field marks are identified by arrows.”

It is hard now, some seventy years later, to appreciate how revolutionary this small green book was for the budding birder. Having spent over a decade working inside a natural-history museum and very familiar with the “old-time” study skins of birds smelling of moth balls and leaking corn starch, this was nothing short of a revolution. You didn’t have to be an ornithologist to know your birds, you only needed Peterson’s field guide and a bird feeder in your own backyard.

In the opening chapter of A Field Guide to Western Birds, “How to Use This Book,” Mr. Peterson wrote in bold typeface, "Make This Guide Your Own," which is exactly what my grandmother did. Within the 61 illustrated plates, my grandmother marked each bird she had seen, where, and when, and with whom. For example, on "Plate 14, Marsh and Pond Ducks," she wrote above the American Widgeon in her red pen, “Tetons, Sept, 1980, Terry.” I remember that trip, I remember that day when we rose before dawn and sat on the edges of the Snake River at a place known as “the Oxbow” with Mt. Moran looming large in the background. When morning light struck the water, there was a pair of widgeons, along with green-winged and cinnamon teals.

My grandmother’s Field Guide to Western Birds is both a photo album and journal of the winged ones that graced her life. She indeed made her field guide personal. The yellowthroat she dated in the spring of 1959 on the Moose-Wilson Road in Grand Teton National Park was still there in 2012. I anticipate seeing him again this May.

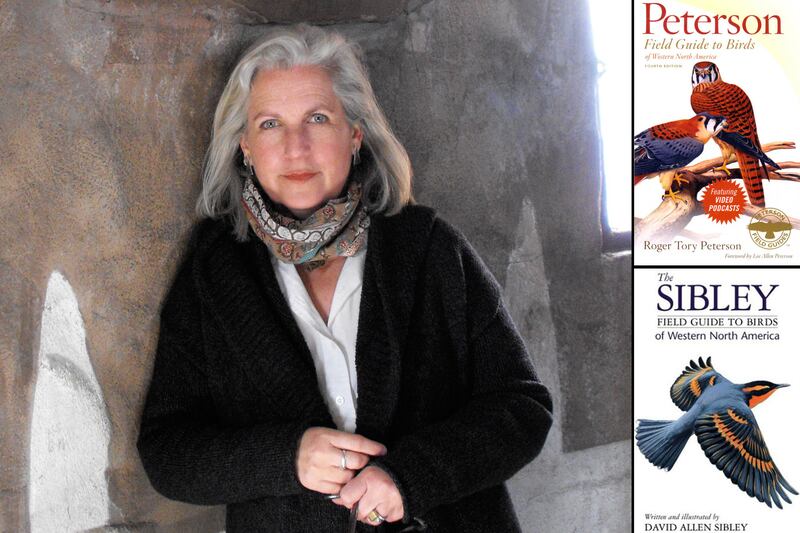

Fast forward, 62 years later: My grandmother missed the publication of The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America in 2003 by fourteen years. She died on June 27, 1989. If Peterson’s bird book was the green linen classic, Sibley’s guide became the gold standard.

I remember the first time I saw David Sibley’s Field Guide to Birds. It was sent to me in the mail as a bound galley. I began reading the book in the bathtub, and if it hadn’t been so beautiful, so utterly stunning in all its detail and depiction of each bird, their behavior, range, and song, I would have dropped it. David Sibley became my ornithological guru, and I did follow him into the field. He felt a bird’s presence before he saw it. And when he did see it, he recognized the nuance of each feather. He was not just identifying a particular species, but a specific individual.

On one particular early-morning bird walk, we were on a mission to see a rare Snowy Owl that had been spotted on the outskirts of Seattle. David, with my husband, Brooke, and I walked the foggy terrain where it had been sighted a few days earlier. We searched the autumn meadow of golds and greens, high and low, wide and deep on the edges of the city. Within twenty minutes of intense focus, and no field guide in hand, David stopped and said, “The owl is not here.” And so we left.

The next day, the Seattle Times reported that the Snowy Owl had moved 22 miles north. David Sibley doesn’t need a field guide to identify birds, he only needs the right habitat.

In between the Peterson’s Field Guide and Sibley’s there have been other field guides that tried to capture the fervor of amateur birders of North America, everything from the Golden Guide to Birds of North America to Audubon’s Field Guide to Western Birds (which used photographs instead of paintings) to the supremacy of National Geographic’s bird book, but none captured our hearts like Peterson and Sibley.

For me, these two artists, Roger Tory Peterson and David Allen Sibley are our own John James Audubon of the 20th and 21st century. No, they are not the stylized master of the 19th century, where each bird appears as an artistic contortion in a gesture of wild elegance, but they are every bit as astute a naturalist and painter as was Audubon. The difference is one of style and scale. Audubon’s lavish illustrations for The Birds of America (now on exhibit at the New-York Historical Society through May 18, 2013, are both mythic and accurate. The 39-by-26-inch images of more than 700 birds species each presented in their distinct habitat is contained in the “Elephant Folio,” considered “the world’s greatest picture book.” Audubon’s paintings hang on the wall. Peterson’s and Sibley’s portraits of birds can fit in our pocket. Their avian portfolios are portable.

So are the birds.

Field guides are my sacred texts. I do not need the Bible or the Torah or the Koran, I only need my pocket picture books that identify who I live among like great blue herons, red-tail hawks, and ruby-throated hummingbirds.

Some women have a dowry in preparation for marriage. I had the complete set of Peterson’s Field Guides from birds, to mammals, to wildflowers, to rocks and minerals and stars. So when a sun-tanned desert rat in the form of a human entered the bookstore where I worked as a 19-year-old and said to his girlfriend, “My one dream in life is to own all the Peterson Field Guides,” and she said, “That’s the dumbest thing I have ever heard!” I could quietly say across the counter where they stood, “I already have them.”

Thirty-eight years later, we are still married, we still have our field guides, and most important, we still use them. I am dreaming of the day I can see a chestnut-collared larkspur, present and rare on the prairie.