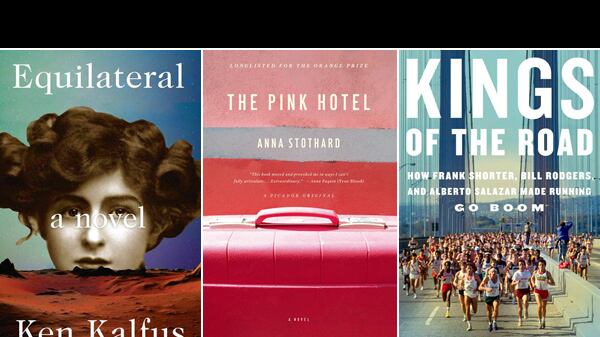

Kings of the RoadBy Cameron StracherThe men who made marathons mainstream began their endurance run in the ‘70s.

In 2012, 487,000 Americans ran a marathon; that figure would have easily exceeded half a million if not for the post-Sandy cancellation of the New York City Marathon, a race in which 9 percent of marathoners participate each year. Today, the sight of “grown men … on the roads in their long underwear and gloves, battling traffic for the shoulder,” is nothing unusual. Running has become a ubiquitous pastime across the country. Approximately 40 million Americans run; Oprah, Lance Armstrong, Paul Ryan, and Katie Holmes have each finished marathons. But Americans’ enthusiasm for the sport is a relatively new one. In his lively, informative history, Cameron Stracher traces the boom of running culture in America back to the 1970s when a trio of single-minded athletes—Frank Shorter, Bill Rodgers, and Alberto Salazar—captured the national spotlight with their intense passion for pounding the road. Shorter’s Olympic marathon win in 1972 marked the first time an American had won the event in 64 years. In the following years, as the three men battled each other for supremacy in races across the country, local road races grew in popularity, “swooshes and stripes became tribal commitments,” and running gained mass appeal. Though his history largely neglects the struggles and victories of female or African runners, Scratcher writes with a true fan’s contagious enthusiasm, glorifying the “close-knit fraternity of the chapped-lipped and knobby-kneed.” He’s at his best when he’s retelling the showdowns between Shorter, Rodgers, and Salazar—how mile by mile and step by step the men pushed each other to the brink, and made history.

EquilateralBy Ken KalfusIt’s 1894 and an astronomer carves a message to Mars in the Arabian Desert.

The shadowy red of planet Mars is typically cast as a belligerent hue. It’s likened to the color of oxidized iron, the color of the hot glow of angry cheeks, the color of crusted blood. But to Professor Sanford Thayer, the dreamy astronomer at the heart of Ken Kalfus’s latest novel, the red of Mars’s terrain is the red of seduction—“red like a ruby or more specifically a red beryl, red like coral, red like an unripe cherry … red like the eye of a nocturnal predator, red like a fire on a distant shore.” It is the spring of 1894, and Thayer, the dreamy astronomer is somewhere between Egypt and Libya, deep in the Bahr ar Rimal al ’Azim, the “Great Sand Sea.” He is directing a workforce of 900,000 men on the construction of a project Thayer is certain marks man’s greatest achievement: The creation of a dug-out equilateral triangle 306 miles long on each side. On June 17, when Thayer calculates the Earth will be closest to Mars, 22 million barrels of petroleum pooled into the three sides’ five-mile trenches will be set aflame, sending out a burning geometric greeting to Martian observers, a historic “petition for man’s membership in the fraternity of planetary civilizations.” Thayer is a romantic—he has chosen the equilateral triangle for its poetic qualities (it is the “most visually satisfying, most inspiring” shape, he is convinced), but the logistics of the project are ugly and grueling. Kalfus has crafted a powerful, mesmerizing story about ambition—and its limitations. The laborers go on strike, Thayer falls into a series of fevers, and his secretary, Miss Keating, strains to push the project through to its completion. As the human failings of the project mount, its symbolic value only grows. But what of the Martians, looking down from above—will they notice and recognize the message? And how will they reply?

The Pink HotelBy Anna StothardA teen wanders Los Angeles during a strange, hot summer.

The protagonist and narrator of Anna Stothard’s startling and raw Orange-prize shortlisted second novel is a nameless 17 year old—a “‘personified shrug,’ a kid on whose face fear, anger, amusement and love all looked the same” according to her father. On the top floor of a pink hotel in Los Angeles, she fills a suitcase with her dead mother Lily’s belongings—a leather biker jacket, a pair of stonewashed jeans, and a handful of dresses, shoes, photos, letters, and maps. After learning of Lily’s death, she’s used her father’s girlfriend’s credit card to buy a plane ticket from London to find out who this woman who abandoned her really was. She has no plan, no friends, no money. Hauling the suitcase past Lily’s passed-out husband and through the fog of drugs and techno that is Lily’s wake, she steps out into the night. The Pink Hotel follows this inscrutable and feral young woman as she spends a strange, hot summer roaming Los Angeles—a city whose “derelict and vast” landscape mirrors her own chaos and desolation—in search of traces of her mother. Starting with her mother’s first and second husbands, and then, working her way through Lily’s old employers, clients, and presumed lovers, her clumsy, needy detective work quickly grows into something much more existential—and hopelessly complicated—than a simple fact-finding mission. The Pink Hotel is a spellbinding story about identity and inheritance, and how we know who we are.

My Bright AbyssBy Christian WimanA poet reflects on faith and dying in the face of cancer.

Christian Wiman, editor of Poetry magazine, was 39 years old when he was diagnosed with cancer. My Bright Abyss is a collection of his reflections on faith as he faced the prospect of death while recovering from a bone marrow transplant. The result is an earnest search for the divine by a believer with profound doubts. Wiman is consumed with articulating his faith, but even his formulation of his fascination with the “insistent, persistent gravity of the ghost called God” reveals the depth of his ambivalence. Is God merely a ghost? Still, Wiman has the wisdom to recognize the necessary mutability of belief: “Even the staunchest life of faith,” he notes “is a life of great change.” This deeply engaged, argumentative monologue is an exercise in reaching, again and again beyond the limits of unbelieving. Wiman’s meditations on life and work span the demands of art and poetry, the cost of ambition, as well as the tensions and harmonies between religious and earthly love. The book takes its title from an incomplete poem addressed to “My God my bright abyss.” Wiman has been only able to complete the first stanza, ending with the words, “and believing nothing I believe this:”; by the end of the book, he’s revised the dangling colon into a period. It’s an exhalation, and, of course, a prayer.

The FlamethrowersBy Rachel KushnerNational Book Award-nominee Rachel Kushner’s new novel is filled with rushing, spinning kinetic energy.

Flames flutter (“like a school of fish,” wrote Saul Bellow), rush (“rushing bouquet of flames”—D.H. Lawrence), even wag (“cooking fires wagged”—Norman Rush)—that is, they are always moving. To throw a flame is like sending a gyroscope on a train ride, and that is how Rachel Kushner’s novel feels—spinning and careering all at once, obsessed with speed. An Italian man in a motorcycle battalion in World War I sees a helmetless German soldier running at him “like a rugby player sent into battle.” That man would become the patriarch of a tire and motorbike empire, and some 60 years later his son, Sandro Valera, an artist who moves to New York, would think of flying on a jet as “no place, no place, no place, and then the approach.” His girlfriend, the novel’s narrator who’s nicknamed Reno, is the one truly in love with movement; skiing, she says, is like “drawing on the mountain’s face, making big sweeping graceful lines.” She’s also a wonderful noticer able to see even static scenes in motion: as she rides a Valera motorbike from Reno to Utah, she sees the flat bottom of clouds as “melting on a hot griddle”; when she follows Sandro to Rome during the politically turbulent ‘70s, she ends up in a crowded apartment with a lot of men in dirty clothes laying around on couches, while she is enveloped in the “sound of frying from the kitchen” and “the texture of energies”; Reno’s aimless velocity lets her observe the ‘70s New York art world, where people gather for dinner parties and chicken tandoori drips from the mouth of a man named Burdmoore Model (pronounced “Modelle”), “the problem of its sauce in his beard.” Kushner’s first novel, Telex from Cuba, reimagined ‘50s Cuba, and received a National Book Award nomination for her efforts. The Flamethrowers not only harnesses the energies of violent Italian politics; it also converts the intensity of radical New York visual art into shining, whirling prose.

—Jimmy So