I have a pretty good memory.

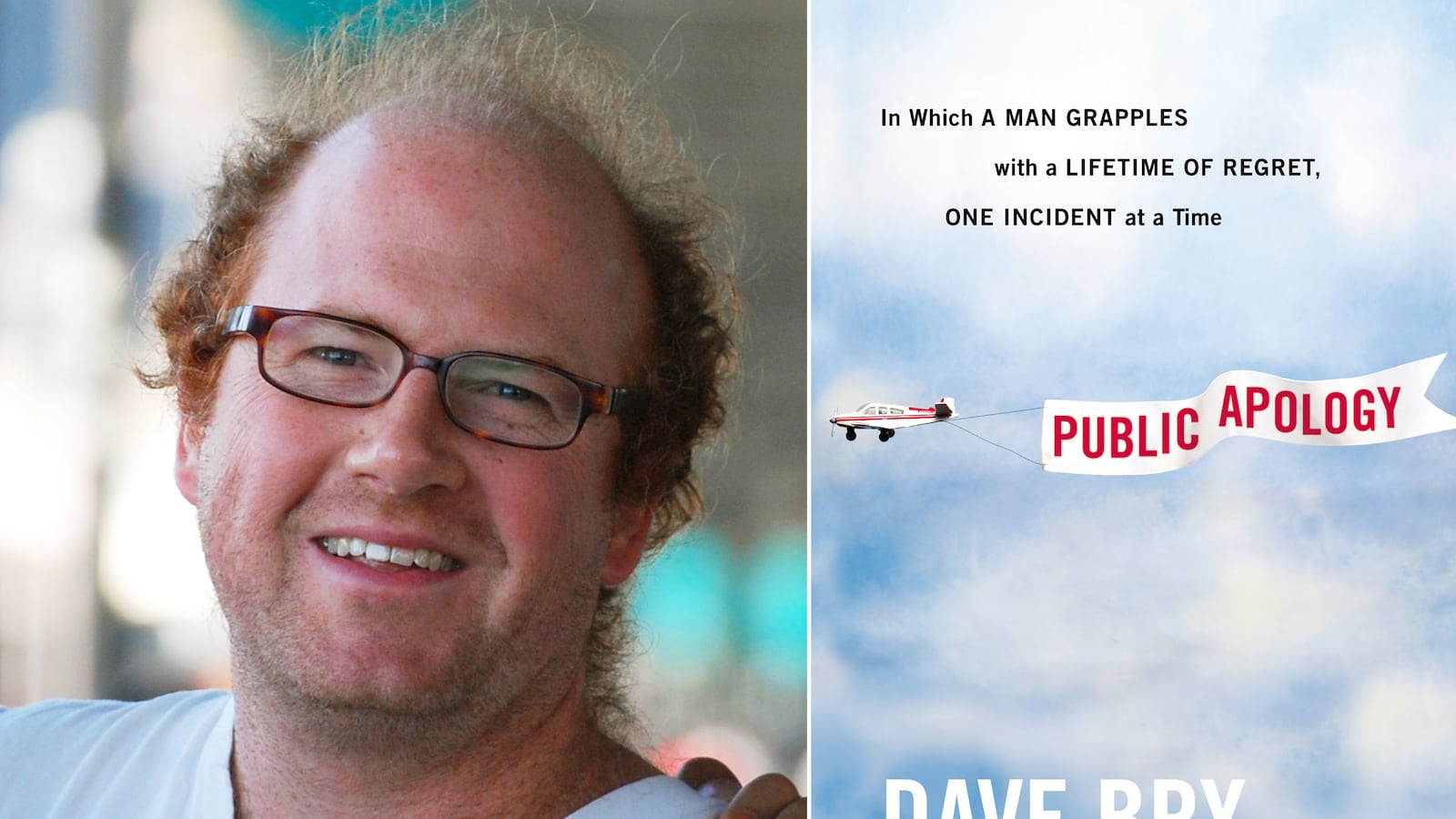

It’s not the best memory. I certainly know people with better memories. And I’m terrible with names. But for things like places and faces and conversations, my memory is pretty strong. Strong enough that I was able to write a book about growing up, starting when I was 12, and fill it with details that I am confident enough in the veracity of to publish as nonfiction. It’s called Public Apology.

But that confidence is not ironclad. After all, writing a memoir is not just an exercise in memory, it’s one in imagination, too—and, as we try to recreate the events of the past, and relay them to readers in compelling scenes that form a narrative, as we write dialogue that we did not record with wiretaps, we’re bound to blur the two. An author’s responsibility to the-truth-the-whole-truth-and-nothing-but-the-truth has been a subject of heavy debate these past few years. In a way that calls into question the bedrock meaning of the words “fiction” and “nonfiction.”

Whole-cloth fabrication on the level perpetrated by folks like Stephen Glass or James Frey is of course beyond the pale. Most everybody agrees that what those two did was very, very bad. But last year Mike Daisy defended the liberties he took with facts in his monologue, The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs, by saying they were necessary in telling a story that would make people care about social issues. He said context changed the meaning of truth (theater vs. radio journalism, say) and that different people had “different languages for what the truth means.” I’ve heard the term “larger truth” used to express this idea. That less important details may be fudged in order to get to a larger, more important truth. It’s very Machiavellian.

Two writers who I highly respect, even love—David Sedaris and David Foster Wallace—have been exposed as fabulists. If only slightly so. In 2008, Sedaris told The Christian Science Monitor, “I’ve always thought that if 97 percent of the story is true, then that’s an acceptable formula.” Two years ago, talking to The New Yorker’s David Remnick, Wallace’s friend Jonathan Franzen said of some of the things that Wallace wrote in his classic essay, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, “those things didn’t actually happen.” And before he died, Wallace himself had admitted a casual attitude toward the distinction in an interview with The Boston Phoenix’s Tom Scocca. “You hire a fiction writer to do nonfiction,” he said, putting the onus on his editors, “there’s going to be the occasional bit of embellishment.”

Learning of those instances broke my heart. But just a little. I still love both writers, and still find great joy and meaning in their work. I would maybe just find greater joy, a bit more meaning (say, 3 percent more), if I still believed, as I once did, that they were reporting the truth, to the best of their ability, in full good faith.

All of this led me to a moment of personal crisis this past year, after I had gotten an edit of my memoir back from my editor. In the book, I tell a story about the day that my father brought home the news that he’d been diagnosed with terminal cancer. I was a senior in high school, a month shy of graduating; he was given two months to live. As you’d imagine, my family was fairly devastated, and my mother asked me to drive to the video store to rent a couple movies to get our minds off the news—comedies, my father suggested; he wanted to laugh.

Operating in what I guess was a state of shock, I made a poor choice at the video store. I’d picked up my girlfriend on the way home, and on our way into the house, she asked what I’d rented and I told her and she stopped me cold—and I’ll never forget the feeling of standing in our carport, looking down at the VHS box in my hand, and seeing the cover of Terms of Endearment.

It was a movie my dad and I had never seen, one we’d been wanting to see before he’d gotten sick. But we knew what it was about. Everybody knew what it was about—Debra Winger had been nominated for every award in the world for her performance of a woman who dies of cancer. I remember standing there at the door to my house, my feet on the green Astroturf that carpeted the step, and thinking to myself, how could you be so stupid? And opening the door and calling my mom over discreetly, to show her the box, and telling her I had to go back to the store, that I had made a terrible mistake, and shaking my head as I closed the door again, backing away. It’s something that has stayed with me since. For 25 years now, I’ve been playing that moment over in my head. I’ve told the story to friends, talked about it with my family, and like I said, I wrote it into my book, in a chapter headed “Dear Mom, Sorry for Choosing Terms of Endearment When You Asked Me To Go Out And Rent Some Movies for Our Family to Watch To Get Our Minds Off the Fact That Dad Had Been Diagnosed With Cancer.” It’s very compelling, right? How emotional trauma can affect one’s thinking.

The thing is, though, that didn’t happen. Not exactly.

While my editor was editing the first draft of the book, I’d sent a copy to my old girlfriend, with whom I’d had very little contact in years and years. I wanted to her read it, to ask how she felt about being included, to get her take. She responded with an email one morning that included the following:

“I was with you when you rented the three movies for your Dad and I will go to my grave believing that Terms of Endearment was not among them. There was a movie in which a person dies of cancer but I think it was more of a comedy. (I know, that sounds silly but my recollection is that it was something smart and funny, maybe Woody Allen.) When we got back you told your mom the story line. She said something to the effect of, ‘It would be great if Dad was in a place to laugh about this but you are right, he's not.’”

Upon reading the words “Woody Allen,” something inside of me felt like it collapsed. I was sure of myself, sure it was Terms of Endearment that I’d rented. We emailed back and forth about it for a couple of hours, arguing. I’d shown the story to my mother and my sister, I told her, and neither of them had remembered it differently. Early in the afternoon, during a lull in our email exchange, a different VHS box popped into my head. Hannah and Her Sisters. Fuck! She was right: Woody Allen. One of the storylines of that movie has hypochondriac Woody enduring a cancer scare. “Brain tumor,” he pronounces, in his Jewish Brooklynese. “Toomah.” He suffers mysterious symptoms, has a cat scan, makes a preemptive suicide attempt (failed, of course, due to over-perspiration)—the whole bit. Something that my dad had laughed about at another time. In the carport. I remembered myself standing there, on the green Astroturf carpet, looking down at the cover of Hannah and Her Sisters. She was right.

I didn’t sleep that night. It was like a whirlpool in my head was pulling me downward. My trust in everything I thought I knew about myself came unmoored. How could I have had been so wrong? Where had Terms of Endearment come from?

The next morning, I called my mom. Her memory of the day was vague, but when I said Hannah and Her Sisters, she agreed that that sounded more right. She too remembered something similar about Terms of Endearment, though, and we talked for a while and came up with an explanation that I now believe to be the truth. The new truth:

My mom remembers us actually watching Terms of Endearment with my father when he was sick. Which jibes with my memory of renting it; it being a movie we had been wanting to see. But it must have been later, sometime that summer. And we didn’t finish watching it. My mom remembers stopping it halfway through, when the cancer stuff started to get heavy.

So I was there, on the step to the door to the carport, looking down at the box, feeling guilty for renting it. I was probably on my way out the door to return it the next day.

Both versions carry some truth. Could I have conflated them, kept it the same? For legal reasons, and to honor the wishes of a couple people who asked, I changed a few names in the book. On the title page, there is a disclaimer. “The names and identifying aspects of some characters in this book have been changed,” it says. Sometimes memoirs say, “In the interest of narrative, certain events have been …”

Maybe I could keep the chapter as it was, but include a correction at the end of the book? That felt like cheating, I imagined my own reaction to reading a book and then finding such an addendum at the end. It left a sour taste. If I couldn’t make a good story out of the events that occurred, in the way they actually occurred, even though my memory of those events had changed, the story was maybe not worth telling.

My editor agreed. She told me to just rewrite it—she thought it would make less of a difference than I did. I happily complied. The chapter is less shocking in its heading, and maybe even a little less compelling in the telling. But it feels better for me seeing it on the page like that.

It’s important to me that I write in good faith.