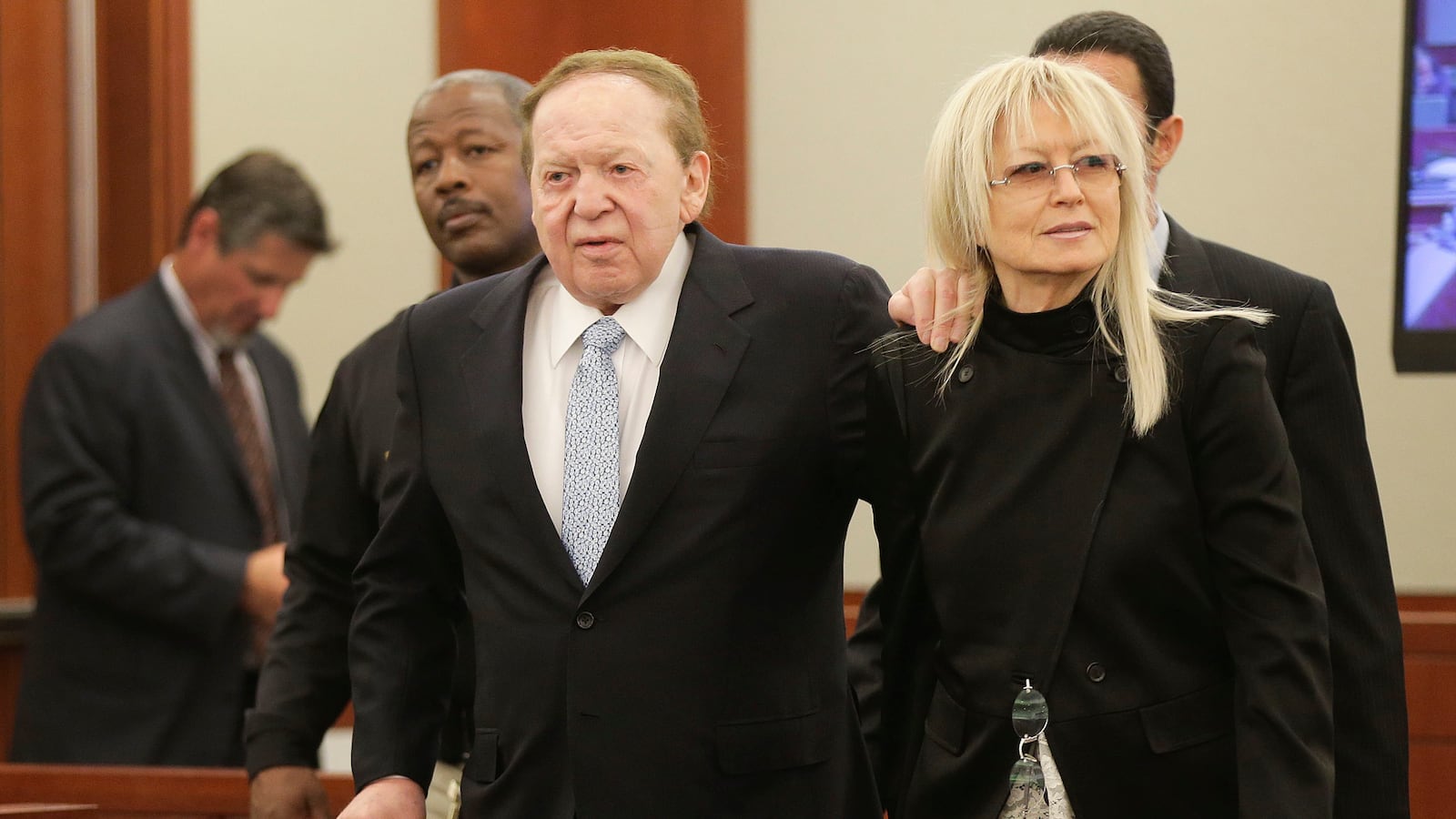

They’re ready for your close-up, Mr. Adelson.

Gaming billionaire and Republican Party underwriter Sheldon Adelson went to great lengths this week to keep cameras out of the courtroom during the retrial of a civil case involving the licensing of his casino in Macau.

The trial began Wednesday, and Adelson, 79, was scheduled to begin testifying on Thursday. But the American casino star’s desperate anti-camera measure—which he claimed was for safety reasons—was an undeniable flop.

Clark County district court Judge Rob Bare was unpersuaded despite the best efforts of Harvard University law professor Alan Dershowitz, whom Adelson brought in to perform a legal backbend worthy of a Cirque du Soleil gymnast. The day before the trial began, Bare sided with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, local television stations, and the Courtroom View Network in allowing gavel-to-gavel video trial coverage.

The original lawsuit was brought by Richard Suen, a former consultant for the Las Vegas Sands. Suen claims Adelson used his connections with influential Chinese government officials to help his gaming company secure the Macau license. The first Suen trial, in 2008, ran for 29 days and resulted in a $43.8 million jury verdict in Suen’s favor (interest bumped it up to $60 million). In 2010 the verdict was overturned by the state Supreme Court on the grounds that the trial judge improperly admitted hearsay statements and left out a pertinent jury instruction.

Although Judge Bare didn’t publicly comment on whether Adelson’s security concerns had merit, he took the unusual step of forgoing a ruling from the bench in favor of requesting that Donald Campbell, the attorney for the media outlets, read some of his commentary: “What better way to demonstrate to the public that its courts are fair and just than to say to the public, ‘Come and view the proceedings yourself and judge for yourself,’” Campbell said. (Full disclosure: Campbell is my lawyer and also represents the Review-Journal, where I’m employed as a columnist. Adelson also sued me into bankruptcy over a trumped-up defamation claim that was eventually resolved in my favor.)

Of course, Dershowitz has argued for decades to increase camera access in the courtroom, a track record not lost on Campbell, who quoted—at first without attribution—from the professor’s 1996 book, Reasonable Doubts:

It makes little sense in my view to censor the only unbiased, direct, and only entirely truthful reporter of the trial—the courtroom television camera—while still allowing extensive coverage by more biased, partisan, and inaccurate human reporters.

When Campbell revealed his source, a smattering of laughter filtered through the courtroom, and Dershowitz smiled. I couldn’t tell whether he was flattered or embarrassed.

Dershowitz’s toughest challenge, however, wasn’t arguing against his own previous statements, it was defending a defenseless position. In a valiant effort, he cited an affidavit in which the former deputy director of the Secret Service said the images of Adelson at trial, once made public and inevitably put online, would endanger the casino baron’s life and put his family at increased risk from haters and terrorists. I wonder if he was talking about the Democrats.

The fact is, Adelson’s political activity long ago made him a favorite on the Democrats’ dartboard. Campbell, in arguing against Dershowitz, noted, “There are literally tens of thousands of still photos of Mr. and Mrs. Adelson on thousands of websites on the Internet. Moreover, there are over 6,000 videos of Mr. Adelson on YouTube alone.”

Campbell also pointed out that Las Vegas Sands and its chairman “routinely file motions to restrict the media’s access to legal proceedings in trials in which they are a named party.”

In a prior case, the Adelsons’ hair-raising rationale was that allowing media access to the trial “would result in constant delay and disruption” due to the reams of confidential material that might be presented, and that the court and lawyers would “be unduly burdened by having to guard against inadvertent disclosure.”

When that argument failed, a new strategy emerged, Campbell said. Las Vegas Sands attorneys filed motions “seeking the sealing and nondisclosure of all manner of information relating to the Adelsons including, but not limited to, their images.”

This week, Dershowitz played to type, defending his client despite his own intellectual inconsistency. The fact that Adelson hasn’t always been so camera-shy made the professor’s argument seem even more comical. As recently as the last presidential-election cycle, Adelson was happy to maintain an international media profile—as long as he basked in a flattering spotlight. As Campbell illustrated in his brief, the supposedly bashful billionaire was a voluble public speaker on topics ranging from Republican Party politics to the future of Israel. The man with grave concerns over the potential dangers of runaway courtroom video testimony had no problem hamming it up for Charlie Rose.

The greater challenge for Adelson, one of the world’s richest men, isn’t whether he eventually has to cut Suen a check. It’s that this civil action isn’t the only costly and time-consuming litigation on his plate.

He faces the threat of far more damage from a legal battle with former Sands China CEO Steve Jacobs, a suit that likely sparked civil and criminal inquiries from the Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Justice over potential violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The Las Vegas Sands has denied wrongdoing and has countered that the allegations contained in the lawsuit are false and malicious.

Let’s just say Adelson has grown a little sensitive on the subject. In February, he filed a defamation suit in Hong Kong against Wall Street Journal reporter Kate O’Keeffe, alleging that she libeled him when she described him as a “foul-mouthed billionaire.” O’Keeffe has been investigating some of the allegations raised in the Jacobs suit from her Hong Kong office. Skeptics might wonder whether the suit was an attempt to chill her investigation. (The suit is pending, and O’Keeffe is still reporting.)

Whatever his reasoning, the irony of Adelson’s ploy to ban cameras is that he’s only called more attention to himself and his business practices. Now none other than the Democratic strongholds of PBS and The New York Times are focused on the trial.