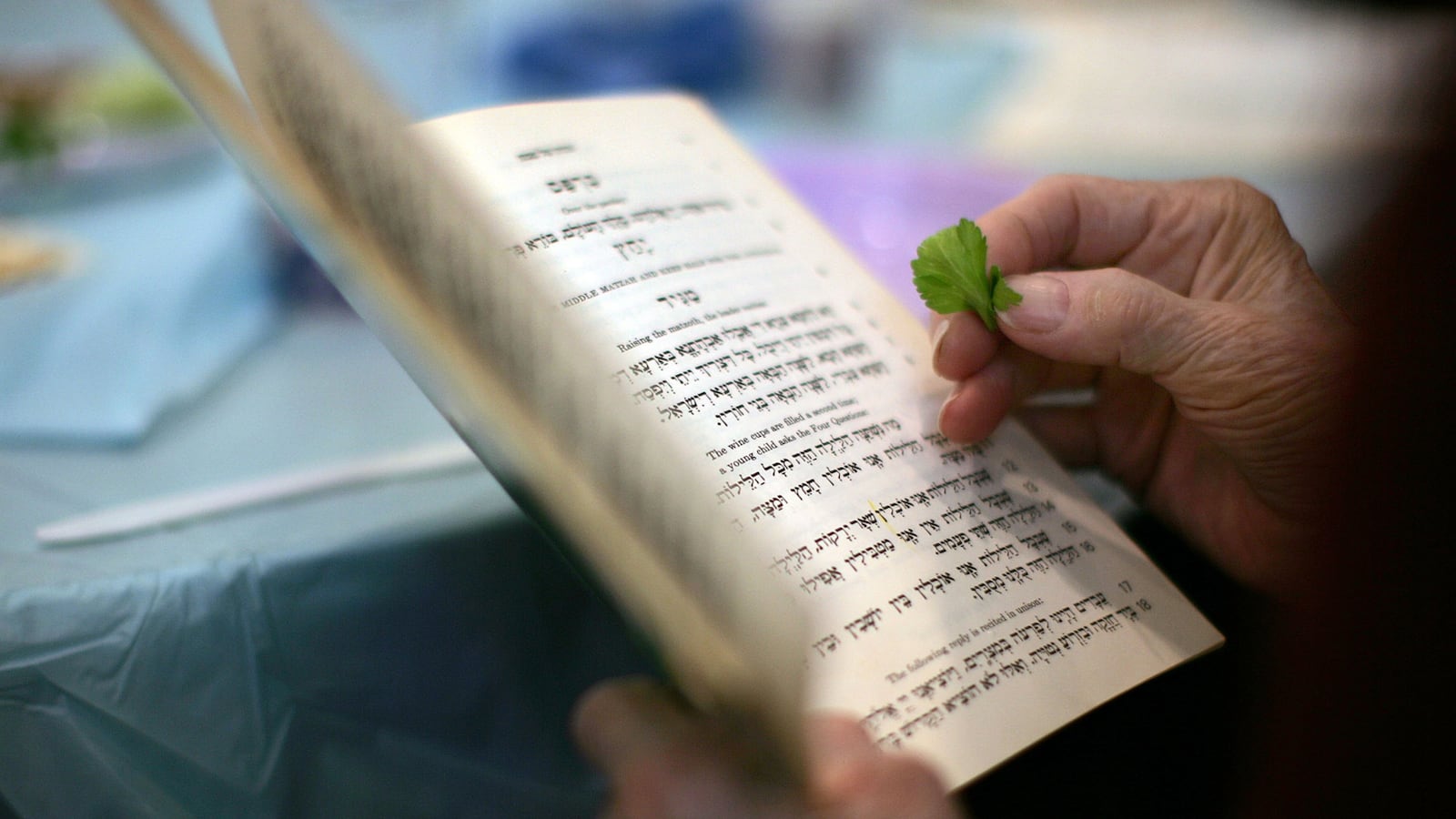

A few weeks ago, I was sitting at a Passover Seder with hundreds of other people on a kibbutz not far from Haifa. As I looked at the faces of those around me in this year’s recounting of the exodus from bondage to liberation, I couldn’t help but think about the many ways in which we were reading the same Passover story, yet understanding it in massively different ways. As a critical educator, I spend a lot of time thinking about how people think about things.

My family, like many others, spills a drop of wine for every one of the ten plagues that were visited upon the Egyptians. It is a small way in which we temper the joyful feeling of liberation with the memory that the Egyptians, another group of human beings, suffered in the wake of the ride to freedom.

As we reached that point in this year’s Seder, I noticed that only a few other people in the room were spilling wine to symbolize our sorrow at any spilled blood, even that of enemies. At that moment, I found myself thinking forward to the upcoming Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israeli Independence Day), which Palestinians call the Nakba (Catastrophe).

Yossi Klein Halevi writes that “Zionism’s hard gift to the Jews was to force us to assume our place among the morally ambiguous nations, pry us from the comfortable self-image of a helpless people to accept responsibility for our fate.” This is true, but it is important to note that moral ambiguity is entrenched in the culture and traditions of the Jewish people.

Spilling wine on Passover is just one example of this. One need only look to one of the essential Jewish traditions of breaking a glass at a wedding ceremony, symbolizing the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, which reminds all those present that even in times of great elation tragedy is a very real part of life.

The same is true of the fluid and unbroken annual procession from the national day of remembrance for soldiers and victims of terror in Israel into a day dedicated to the celebration of independence. Much of Jewish tradition and culture is rooted in the hard truth that happiness and pain come hand in hand.

So why are we so afraid to learn about the pain of others in the wake of Jewish national liberation? Why do we go so far as to pass laws that ban public funding from going to institutions that make mention of the Palestinian Nakba?

Why has the State of Israel turned away from a tradition of critical thought that is rooted in the story of the biblical Jacob, a critical thinker who wrestled with his own identity and that of the world around him? It was that process of wrestling that led Jacob to become Israel.

The minimum that we should do is to learn together about the deep tension between the narrative of independence and that of catastrophe or Nakba. Instead we attempt to create a chasm of silence in order to pretend it doesn’t exist.

Learning about the Nakba does not mean hating ourselves or our culture. It does not mean deciding that the idea of Jewish self-determination is inherently wrong because of wrongs in our history. It means facing our history of heroism and hate and blood and birth and it means building on that so that we can create a more just reality today—just for the Jewish people and just for the Palestinian people.

Finding space for multiple narratives and making room to learn about the Nakba, which Israeli society has deemed unthinkable, is an absolute necessity. It is naïve to think otherwise. What is really unthinkable is that there is any moral alternative to peace, justice, and—one way or another—sharing this land.