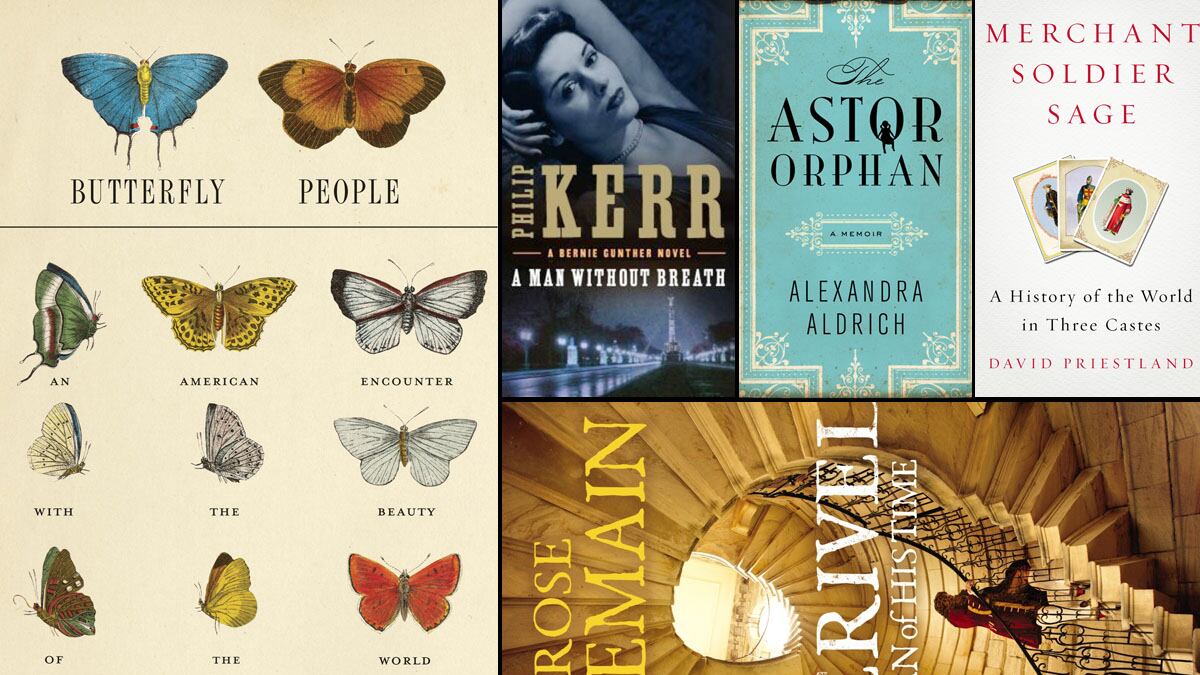

The Astor OrphanBy Alexandra Aldrich

A debut memoir of an Astor descendant’s childhood spent living in crumbling Rokeby Mansion.

Perhaps the reason that large, old mansions feel like characters in their own right is that they are given proper names: ostentatious Brideshead Castle from Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, or ignominious Darlington Hall from Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. The American cousin to these homesteads, central to Alexandra Aldrich’s debut memoir The Astor Orphan, is Rokeby, a 43-room mansion in the Hudson Valley built by the Astor family in tribute to their own enormous wealth and influence. But by the time Aldrich, an Astor descendant, was born into it, the house had fallen into disrepair, much as her branch of the family had fallen into a kind of poverty—that is, well below the level of comfort that Astors were taught to expect for themselves. This is the story of Aldrich’s trying childhood there, populated with a well-drawn cast of her eccentric relatives struggling to rectify their past with their present. “The house gives each of us—the impoverished descendants—an identity,” she writes. “And we live off the remains of our ancestral grandeur.” What’s most notable here is the melancholy that Aldrich elicits throughout, a sensitivity towards time and fate reminiscent of a painted landscape in which a shepard stops to rest his flock among the forgotten, grown-over ruins of a once mighty castle.

Butterfly People By William R. Leach

The expansion of American interest in butterflies and naturalism coincides with increased industrialization.

It may seem that the only people that would be interested in a 416-page book about butterflies would lepidopterists. But in Butterfly People, Columbia history professor William Leach (whose previous Land of Desire was a National Book Award finalist) uses the rapid expansion of American interest in butterflies after the Civil War as a way into man’s arduous process of understanding his place in the order of things. Leach shows how the dawn of ecology (the term first gaining widespread use in the 1880s) was an awkward time for the science of nature, as it struggled to separate itself from a religiously tinged notion that man was somehow set apart, and that everything in nature could only be explained by its benefit to the human experience. (One lepidopterist at the time concluded that the beautiful wings of the butterfly must surely exist only as a cherry on top of the human aesthetic enjoyment of the world.) Leach describes the science of this period as a “fascinating mix of scientific confidence and human longing,” and this book treats both aspects with equal care and well-researched precision.

A Man Without BreathBy Philip Kerr

Another installment in the Gunther series sees the Berlin Bull sent to the Eastern Front to investigate a mass grave.

In a literary world glutted with pithy detectives playing by their own rules, it’s hard for one of them to stand out from the pack. But Bernie Gunther, the recurring protagonist created by Philip Kerr, walks a unique beat. Although he operates during the noir golden age of the late ‘30s and ‘40s, he haunts the streets of Berlin instead of New York or Los Angeles, and his employer is the Wermacht’s War Crimes Bureau. The Gunther novels (this is the ninth) span from the pre-war Weimar years to the post-war occupation, but A Man Without Breath finds him in the thick of 1943, a month after Germany’s disastrous defeat at Stalingrad. Gunther is sent by his superiors to Smolensk to investigate reports of a Russian massacre of Polish troops in 1940. Goebbels believes that if the crime can be proven, it will crack the cohesion of the allies, and in the insane logic of war, weaken the victor’s vision of the Nazis as distinctly evil. This is the most intelligent brand of crime fiction, and there is moral complexity here in spades; Gunther is not a villain, but he is wearing the wrong uniform.

Merivel By Rose Tremain

In the sequel to Restoration, Robert Merivel is back, now in middle age, with another courtly farce.

When he was a younger man, Robert Merivel was quite the rogue. Rose Tremain’s bestselling 1989 novel Restoration detailed the physician’s debauched misadventures in the court of King Charles II. That the role was played by Robert Downey Jr. in the film adaptation is strong testament to his rakishness. In Merivel: A Man of His Time, the long-awaited sequel, Merivel has aged 15 years since readers last saw him, and things have slowed down considerably. In an attempt to reinvigorate his life, he travels to Versailles, where he soon finds himself up to old ways, bumbling through another string of hilarious and often poignant follies despite himself, adopting a bear and following love (and a fair measure of lust) to Switzerland. The stilted prose can take some getting used to (“‘Merivel,’ said I to myself, ‘to sit alone like this, day after day … will assuredly bring you to a dark despondency’”) but this is less of an affectation and more of an element of the courtly humor. Fans of Restoration will not be disappointed.

Merchant, Soldier, Sage By David Priestland

Human history as told through the competing wills to power of three elements of civilization.

The story of man, Oxford academic David Priestland writes in his new big-idea history entitled, can be told through the will to power of three castes of civilization. The first is the soldier, responsible not only for conquest (or “defense,” in more recent parlance) but also aristocracy and statecraft. The second is the sage, who evolved from priests, to bureaucrats, to the educated “wielders of ideas” like Karl Marx, and finally into today’s expert and technocrat. The third caste, for which Priestland reserves the lion’s share of his suspicion, is the merchant, bankers and businessmen who grew out of a mercantile tradition in England and the Netherlands and rose, eventually, to the most recent position of dominance, where they have remained. When one caste gains too much power, it brings its own brand of disaster. The book covers almost the entirety of human history, but really serves as an extremely long-tailed investigation into the financial crisis of 2008 and how civilization’s failure to properly rein in the merchant in its wake might negatively affect the future. Are there poorly drawn conclusions scattered within this Grand Unified Theory? One would need about 10 different Ph.D.s to accurately say. But Priestland keeps things moving at a lively and readable pace, and whether his theory is to be vindicated or disproved is only for future historians to decide.