Professor Yeshayahu Leibowitz lived on Ussishkin Street in Jerusalem. The street was named by Menachem Ussishkin himself. An early Zionist leader, prideful, pugnacious, Ussishkin headed the Jewish National Fund for nearly 20 years. In 1931 he built an imposing house on what was then Yehudah Halevi Street, named for the 12th century philosopher-bard. All the streets in the new neighborhood of Rehaviah were named for poets and philosophers of the Spanish Golden Age. For his 70th birthday, Ussishkin decided to honor himself. He ordered JNF workers to remove all the signs saying "Yehudah Halevi" and replace them with ones that bore his own name. And so the name of the street is Ussishkin unto this day.

You can't imagine Yeshayahu Leibowitz doing this. If Leibowitz knew that city council members would one day propose naming a street after him and that the proposal would cause so much loud opposition that the mayor would have to drop it from the agenda, as happened last week, he would have felt honored by the controversy: The Yeshayahu Leibowitz Memorial Upheaval.

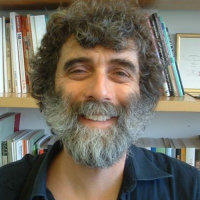

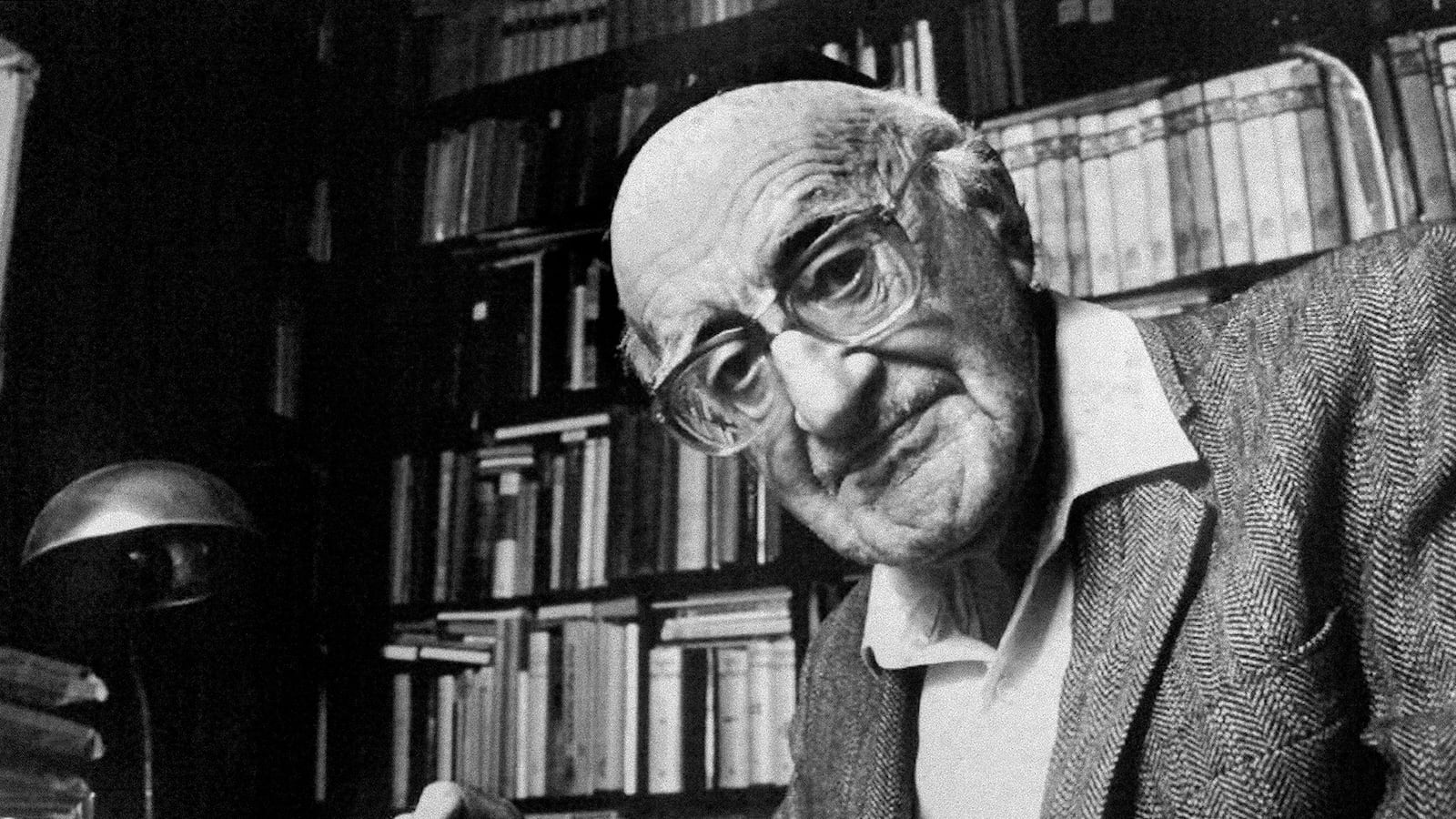

The last time I visited Leibowitz was 19 years ago, on Israeli Memorial Day, 1994. I came to his home to pick up a handwritten article on the weekly Torah portion that he wrote for my magazine. Picking up Leibowitz's articles was the very best part of my job, because he would invite me in and talk, which is to say rage, for an hour or so. There was in fact enough space between the books to sit down in his living room. Between the top of each row of books and the bottom of the shelf above, more books in sundry languages were squeezed in on their sides. I don't know how many languages he spoke, but English was not among the first four he'd learned. Each time he'd hand me an article, he'd say, "You know English is not my mother tongue. You will have to edit it." The second part of this statement was false: All I had to do was read his shaky handwriting and type the article. His English was polished. His thoughts were precise, as if cut with a diamond-cutter's tools. A beautiful fury shone from within them. I believed back then with a perfect faith that Leibowitz had lived into his nineties because the Angel of Death refused to obey the order to take him, insisting that a black flag of illegality flew over it.

During our conversation, he progressed from the evil of making the nation and state into ultimate values ("That is Nazism!") to the danger of connecting Zionism to messianism ("The messianic idea is the greatest disaster in Judaism!") to the mistake of reading the Biblical prophets' words on redemption as forecasts of actual events. When he got to the last point, he told me to bring him Tractate Yevamot of the Talmud from a shelf. He opened to page 50a and pointed to a line in Tosafot: "The prophet predicts only that which should be." The emphasis was his: a high quivering shout, a forefinger stabbing upward.

Every person is built out of contradictions. But Leibowitz's contradictions were larger. They were flagrant. They inspired awe. The precise philosopher was reckless in his condemnations. He wanted both to convince and to offend. Religion tied to the state, he said, was prostitution, and state funding for religion was "a whore's pay," as in the verse, "You shall not bring a whore's pay…into the House of the Lord." Following a path of strict logic, the rationalist concluded that the only acceptable reason to follow the Torah's commandments was illogical love of God. Any other motivation was idolatry. Even grounding mitzvot in morality was idolatrous, he said, because morals served human needs.

Yet the man with the black skullcap had been the country's courageous voice of moral wrath at least back to the Qibya affair in 1953, when Ariel Sharon led troops on a retaliation raid for a terror attack and killed some 60 civilians. Very soon after the Six-Day War, he publicly warned that remaining in the occupied territories would corrupt Israel to the core. Not every one of his predictions has come true, at least not yet, but too many have. The rational philosopher was a prophet. Not since Jeremiah went into exile has anyone raged against injustice in Jerusalem like Leibowitz. He kept on, lecturing and writing, until he died in August 1994, at age 91.

Can you imagine someone naming a street after Jeremiah in his own time? Would it actually honor Leibowitz to name a street for him in Jerusalem when half the city is still under occupation in all but name? Is Jerusalem yet worthy of a Yeshayahu Leibowitz Street?

To paraphrase Kafka, who was merely 20 years older than Leibowitz: Jerusalem will deserve a street named for Leibowitz not on the last day of occupation, but on the very last day. It will deserve a street named for him only when it is no longer necessary.