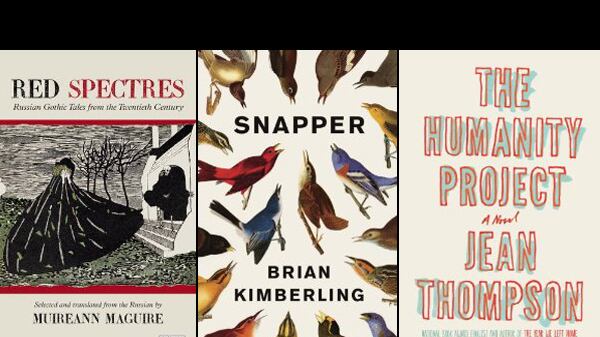

Snapper By Brian Kimberling A lovestruck ecologist’s mission roaming the woods and fighting for songbirds.

Evansville, Indiana, is the setting of this debut novel, but it’s easy to mistake the city for a character in this book. “If Indiana is the bastard son of the Midwest, then Evansville is Indiana’s snot-nosed stepchild,” the protagonist, Nathan, observes. Nathan is an ecologist who spends his days roaming the forests in a truck held together with duct tape and Band-Aids, tracking birds, using trigonometry to calculate nest locations, composing wry, anthropomorphizing field notes. No matter how far Nathan loses himself in the woods, he can’t forget about his on-again, off-again girlfriend, the enchanting, brilliant Lola, whose shifting whereabouts are impossible to track. (Nathan carves Lola’s name into trees marked to be cut down.) With growing deforestation, time is running out for the songbirds, and Nathan goes to court to fight for the birds’ home. Little by little it becomes clear that greater than Nathan’s passion for Lola is his love for Indiana, the stubborn land that opened its arms to him when Lola was nowhere to be found.

The Humanity Project By Jean Thompson An elderly widow seeks help in giving her money away through a foundation.

Can you pay or coax people to be good? Jean Thompson’s new novel asks these questions as a matter of practicality. The wealthy Mrs. Foster has a lot of money to give away. The elderly widow enlists a spinster nurse with New Age impulses named Christine to help realize her vague aspirations for bettering the world through a foundation she calls the Humanity Project. Christie is honored but puzzled. How will the foundation operate? “Was ‘goodness’ something that could be objectified and measured? Did society benefit directly from individual virtue, and therefore have incentive to promote it?” These are heavy quandaries, but the art of this novel lies in something more subtle. Thompson’s characters are quietly linked together: Christie’s neighbor is a hapless divorced father whose daughter is a survivor of a school shooting. The daughter strikes up an unconventional but intense friendship with a boy named Conner. When Conner’s father hits a rocky patch, he finds work with Mrs. Foster. None of them know the full extent of each other’s troubles, though their daily dramas are inextricably connected. Thompson weaves together their broken dreams and mundane concerns into a larger pattern. Humanity reveals itself in fits and starts.

Red Spectres Translated by Muireann Maguire

Forgotten gothic tales from a tumultuous chapter of Russian history.

Readers familiar with Chekhov, Gogol, Pushkin or Turgenev have already tasted some 19th-century Russian gothic literature. Harder to find, however, are early- to mid-20th-century examples of the form—after the Russian Revolution, gothic literature was essentially blocked from publication. A new collection translated and edited by Muireann Maguire showcases stories previously obscured by censorship. The darkness and dissonance of these tightly constructed tales reflect something of the political turbulence of Soviet Russia. “In the Mirror,” by Valery Bryusov and “The Venetian Mirror,” Aleksandr Chayanov’s response to Bryusov’s story, both explore the limits of sanity, as their protagonists do battle with their reflections. Like other stories in the collection, they dabble in the supernatural so as to illuminate the strangeness of the country’s transition. “The supreme irony of Soviet efforts to expunge the Gothic from Russia’s cultural legacy is that such attempts merely guaranteed its resurrection,” Maguire explains. Nearly a century after the time, the stories collected here are still powerful in their disaffection. As a character in Aleksandr Grin’s “The Grey Motor Car” puts it, “A dash of distortion lasts a long time, if not forever.”

My Animals and Other Family By Clare Balding

Horses are a girl’s best friend in this warm memoir.

In this warm memoir, BBC sports broadcaster Clare Balding takes readers on a tour of her childhood as the daughter of a racehorse trainer. “Boys at least had the advantage of registering a presence,” but as a girl, Balding was left alone to run wild with the other creatures of her parents’ property. She learns to ride a horse at roughly the same time she starts to walk, and grows up marking her years by memorable Grand National or Derby wins and counting how many times she falls off the saddle. (After her first big fall at age 3, she breaks her collar bone. Her father insists that 100 falls make a good jockey.) Her family is used to saying, “Women ain’t people,” so Balding rises to the challenge, first to prove her worth on horseback, and later, to prove her worth at Cambridge University. Though she finds success in both realms, this volume is less an accounting of Balding’s personal victories than a tribute and fond remembrance of the horses and dogs that Balding shared her childhood with. Each chapter is named for a different animal: her first dog, the pony she shared her breakfast cereal with, the charismatic racehorse that winds up funding her education. When, at age 9, she carves Clare <3 Frank in a tree, Frank, is of course not a boy but a pony. The best friends and biggest loves of her early life are these horses and puppies she ran free with.

The Other Side of the Tiber By Wallis Wilde-Menozzi Reflections on Italy’s deep enchantments.

Wallis Wilde-Menozzi is just a student in a miniskirt looking for adventure when she first visits Italy. The brief encounter proves fateful. Four years later, she is back, a 26-year-old woman starting over alone after running away from a failed marriage and an unfulfilling academic job. Italy offers the opportunity to renew her spirit. “Italy possesses extraordinary master keys that it offers to everyone,” Wilde-Menozzi writes. The winding currents of the Tiber River, the beams of light filtering through the dome of the Pantheon and the shadows of John Keats’s room completely captivate her. In this elegant volume, Wilde-Menozzi turns her patient gaze on everything from the red brick walls of Siena to the volcanic rock of Etna. This is not a guidebook but a passionate account of a country’s contours and their hidden wisdom. Wilde-Menozzi comes to Italy with serious intentions, and is rewarded accordingly. “In Italy, the tangled and mysterious strata of those who lived before surrounds, consoles, horrifies, surprises, suffocates,” she writes. “But it never concludes that mere diversion is the end.”