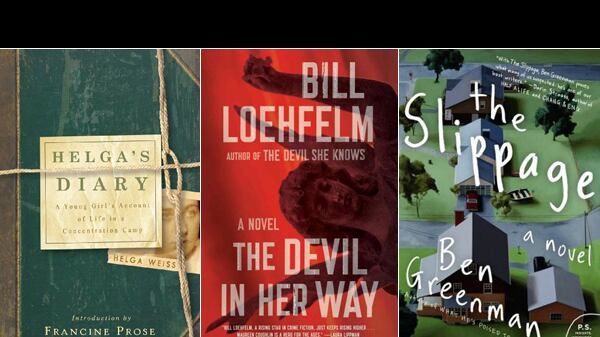

Helga’s Diary by Helga Weiss

A young Jewish girl under the thumb of Nazi Germany keeps a diary of her time in the ghettos and camps.

There’s no such thing as a definitive account of surviving the Holocaust. No one person lived all the horrors or found every way to express the horrors. Helga Weiss adds a new story into a shrinking community of survivors with her edited diary, full of life despite the void of humanity that surrounds her.

This young girl is adaptable. The trials of life under Nazi guard barely keep pace alongside adolescent politics and the make-do normalcy that Helga constructs for herself despite the worst conditions. Though cramped cattle cars and 12-hour shifts in a factory strain her young body, her resilient spirit reenergizes at little miracles—an extra article of clothing to stay warm, or likewise a headscarf given in the cold factory by a sympathetic guard. At times the struggle of this young girl in the face of evil becomes so real that you’ll notice yourself adjusting your blanket and thermostat right along with her as she shivers in the worst of conditions.

Overall, the plurality of voices—of young Helga and the author making revisions and addendums to the text decades later—mesh well. At moments throughout the narrative, however, discord strikes. Knowing that the writer has returned to these pages before publication plants suspicion. Which observations are genuine, and which ones are made with a back-turned eye on her childhood? Though much of the text was left intact, the author says in her introduction that some parts were rearranged, and some thoughts were tweaked. Sometimes it’s clear which Helga is writing; sometimes it’s a bit muddy. But there’s added perspective here and there from a valuable storyteller’s editorial liberties, and we benefit from the context.

—G. Clay Whittaker

The Slippage by Ben Greenman

A man struggles under the weight of his wife’s bold ultimatum: build a new house or end the marriage.

Things are fine on the surface for William Day. He has a paying job, friends, a home to return to each night where his wife, Louisa, and his dog wait for him. But after a dinner party, Louisa lets him know that she feels her life has become stagnant, and she offers him an ultimatum: build a new house on a plot of land she’s bought, or let the marriage die. As if the decision isn’t hard enough, things become complicated when an old flame moves in just across the street.

The narrative is paced and comfortable, peppered with bursts of predictability. Greenman employs a textbook approach to examining a relationship. Communication is second to observed mannerism; the characters Louisa and William are constructed of memories: “There was a park bench where Louisa had kissed him roughly. There was a canal where William had, half in jest, thrown a pebble he pretended was his wedding ring.” Greenman puts new spins on clichés, and rescues his story from mediocrity by finding new ways of talking about melancholy. Louisa and William’s house as it stands represents more than a shared past—it becomes an extended metaphor for everything they’ll have to put behind them if the relationship is ever going to work.

—G.C.W.

The Devil in Her Way by Bill Loehfelm

A young officer’s struggle to prove herself comes to a head when there’s more to a routine call than meets the eye.

Punches are flying from page one of this electric thriller. New Orleans officer-in-training Maureen Coughlin, red-faced and bruised after a suspect catches her off guard at the scene of a domestic violence call, happens into a bit of luck when her backup discovers a sizable stash of drugs and guns in the offending couple’s apartment. But while the other officers sigh with relief over the small victory, Maureen notices something questionable between two neighborhood kids. She wants an explanation of the cryptic glares and whispers, but they disappear. Eventually her search leads her to a mysterious criminal figure who uses children and discards them like paper napkins.

Maureen was an unwitting player in a scandal when she first appeared in The Devil She Knows as a Staten Island waitress wrapped up in the murder of her boss. Now, a book later and transported to her beat training in New Orleans, she’s tougher, grittier, and more focused. Loehfelm jumps on this early, and shows us a hardened Maureen rolling with the punches, fueled by an ambition to be the best cop she can. Maureen’s history of victimization and her winding journey through a living New Orleans mean there’s more at work here than a static cop drama.

—G.C.W.

Serving Victoria by Kate Hubbard

A history of Queen Victoria’s household drawn from correspondences and diaries.

Kate Hubbard’s Serving Victoria: Life in the Royal Household is a history drawn from the correspondence and diaries of Queen Victoria’s most trusted help. The narrative hinges on six key players in the Queen’s long life: Sarah Lyttleton, Victoria’s worldly and doting governess; Charlotte Canning, a haughty and discreet lady-in-waiting; Mary Ponsonby, a judgmental but romantic maid-of-honor; Henry Ponsonby, Mary’s husband and Victoria’s private secretary; James Reid, an unemotional and trustworthy medical attendant; and Randall Davidson, the very sympathetic Dean of Windsor. Conscripted to serve, these people are separated from their children only to mother others. Hubbard describes the ladies-in-waiting, the baronesses, and the randy lords as “a small group of people, not necessarily sympathetic to each other, lacking in occupation, cut off from family, friends and the ‘outer world.’” The appeal in Hubbard’s story is the excitement in an otherwise dull existence. Call it the sensuality of stiffness. There are scandals and great loves, pregnancies and mourning. The emotional complexity is as entertaining as (and more astute than) most upstairs-downstairs soaps, even those written by Julian Fellowes. In gossipy and vivacious prose, Hubbard conveys a life where there’s nothing to do but have and obsess over relationships.

—Jen Vafidis

A Delicate Truth by John le Carré

The spymaster takes on the absurdly corporate air of the war on terror.

A Delicate Truth is John le Carré’s latest novel, his 23rd in a career that has made his last name synonymous with the messiness and intrigue of British intelligence. Since Sept. 11, the spy novelist has drifted to another topic, namely the war on terror, and A Delicate Truth certainly represents this tendency. Our protagonist, Toby Bell, is an English bureaucrat investigating the cover-up of Operation Wildfire, an extraordinary rendition hailed as a success. Le Carré’s main point seems to be the absurdly corporate air of anti-terrorist intelligence, and this idea, while on the mark, isn’t as exciting as his others. The telling of Wildfire itself reads almost like a farce—with a few pratfalls, it would be Wodehouse-level comedy. But even when you start to feel disinterested in the story, le Carré’s sparky prose saves you. He perfectly distills the despair hidden in what’s normal: plain offices, miserable canteens, dank hotels that smell of lavender and cigarettes. Patients in a hospital stare at a door marked “Assessment” under “strips of sad white lighting,” and nudnik recruits stare at their cell phones, waiting for them to recharge. It’s all very English, actually, in both form and content, and the familiar steeliness of le Carré’s themes is ever-present. Loyalty to the crown is tested; consciences are checked; and nothing is more terrifying than, as this novel’s protagonist puts it, “a solitary decider” asking himself how on earth he talked himself into this mess.

—J.V.