It is one of the first rules of politics: Never get into a fight with people who buy ink by the barrel.

But if you can buy your own ink, the paper it’s printed on, the barrels themselves, and have a whole newsroom toiling in your name, perhaps the old rules don’t matter.

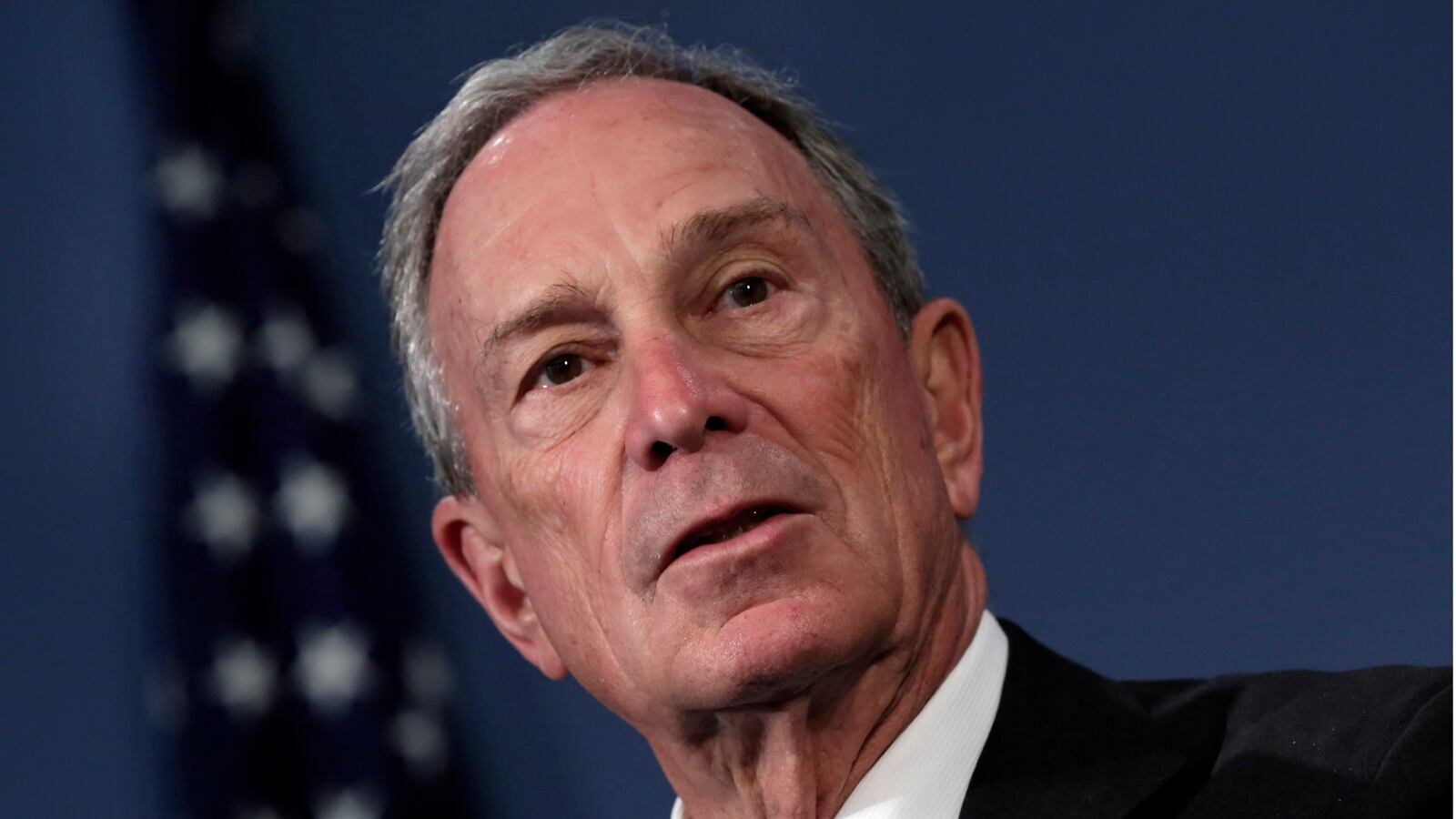

On Tuesday, standing before the brass at the police headquarters in lower Manhattan, New York’s billionaire mayor Michael Bloomberg defended his administration’s policing practices, particularly its stop-and-frisk policy, which gives police officers broad leeway to stop and search people on the street.

The policy has come under harsh criticism by all four of the Democrats vying to replace Bloomberg next year, as well as by civil rights and civil liberties groups, as unfairly targeting minorities. But Mayor Bloomberg directed much of his ire at perhaps the only institution in Gotham that can rival him in clout and influence: The New York Times, whose editorial page has consistently deplored the practice—a recent piece called stop-and-frisk “widely loathed and constitutionally offensive”—and whose editors have given prominent newspaper real estate to police abuses.

The mayor accused The Times on Tuesday of hypocrisy for covering stop and frisk extensively, but failing to cover the murder of a 17-year-old in the Bronx—a murder, the mayor implied, of which there would be many more were it not for his public safety measures.

“There was not even a mention of his murder in our paper of record, The New York Times. All the news that’s fit to print did not include the murder of 17-year-old Alphonza Bryant,” the mayor said. “Do you think that if a white 17-year-old prep student from Manhattan had been murdered, the Times would have ignored it? Me neither.”

Bloomberg tweaked the editorial board over that “widely loathed” comment, noting that it came four days after the unreported murder of Bryant.

“Four days after Alphonza Bryant’s murder went unreported by the Times, the paper published another editorial attacking stop-question-frisk. They called it a ‘widely loathed’ practice…Let me tell you what I loathe. I loathe that 17-year minority children can be senselessly murdered in the Bronx—and some of the media doesn’t even consider it news.”

A Times editor was unavailable to respond to the charge of why the paper did not cover the murder in the Bronx. But it is worth noting that the paper of record, as Bloomberg calls it, isn’t a crime blotter, and it’s coverage of local news has shrunk dramatically over the last decade. The city’s other two dailies didn’t give it much notice, either, and a Times spokesman said the paper in general only writes about fewer than a quarter of the murders each year recorded in New York City.

“Mayor Bloomberg is trying to deflect criticism of the city’s stop-and-frisk practice by accusing The New York Times of bias,” added Danielle Rhoades Ha, the Times’ communications director, in a written statement. “Among those critical of the practice is The New York Times editorial board, which is separate from the news side of the newspaper. The Times aggressively covers violence in the city’s neighborhoods, and to select one murder as evidence to the contrary is disingenuous. His claim of racial bias is absurd.”

The episode marked a rare clash between the mayor and the Times. The editorial board has knocked Bloomberg on some of his civil rights stances over the past decade, but it has endorsed him twice during election season, suggesting in 2005 that “he may be remembered as one of the greatest mayors in New York history” and “enthusiastically” backing Bloomberg in 2009.

Although Ed Koch used to carry copies of articles he disagreed with to the lectern, most New York City mayors have been unwilling to take on the Times directly. Bashing the mainstream media’s house organ has been much more of a red state political proposition. Bloomberg in particular has seemed impervious to criticism, and the prestige of a Times endorsement has meant that few other New York pols have been willing to cross him. That Mayor Bloomberg did so now, associates, advisers, and local political insiders say, is due to a combination of factors, including a heated mayor’s race that has led the leading Democratic contenders to curry favor with the Times by bashing the current mayor’s policing policies. The mayor is also defending one of his cornerstone achievements—keeping the city’s crime rate low—as he prepares to leave office in eight months, when he won’t have to worry about the paper’s opinion about him anymore. There have also long been rumors that Bloomberg could use his vast wealth to one day buy the paper outright.

On Tuesday, Bloomberg did more than bash the paper, he also accused it of acting cynically and in bad faith, of letting the political position of the editorial board drive the news coverage.

“You can attack a newspaper for a stance you may disagree with, but you can’t blame them for the death of a 17-year-old,” said George Arzt, a Democratic political consultant who was both the City Hall bureau chief for the New York Post and a spokesman for former mayor Ed Koch. “I think that he is just taking an extreme view. Anybody who has been in a newsroom understands that decisions are made by reporters and editors and that there is no great conspiracy. Everyone putting out a newspaper is trying to get it right, trying to make deadlines, trying to get as many scoops as they can get. They are not saying, ‘Hey, let’s go after this political point today.’”

In taking aim at the newspaper, Mayor Bloomberg may also have provided cover for his would-be successors to be less in the thrall of the editorial board’s politics. And some of his allies couldn’t help but note with glee that after years of dodging criticism, Hizzoner finally fought back.

“Are they going to squeal because he punched back?” said Bill Cunningham, a former Bloomberg spokesman. “If you want to dish out you better take it. Maybe it will remind The New York Times that they can be criticized, too.”