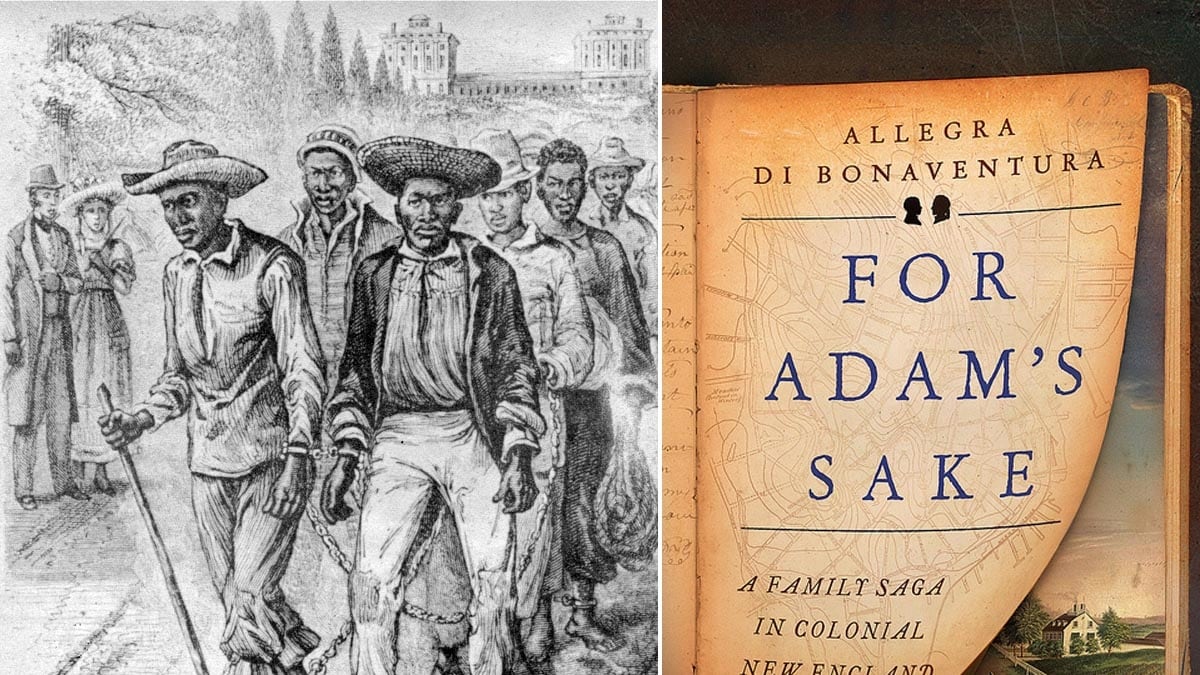

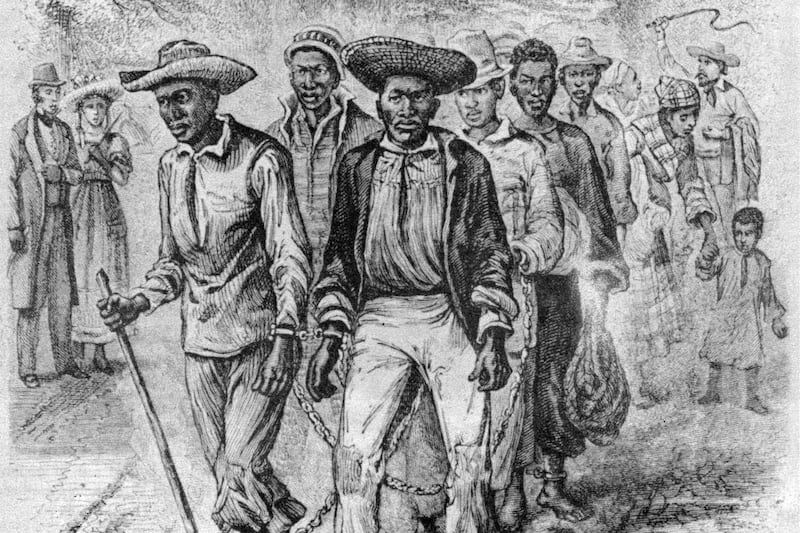

It may come as a surprise to some, but slavery existed in colonial New England, not just the South. This fact animates For Adam’s Sake: A Family Saga in Colonial New England, the first book by Allegra di Bonaventura, a historian of prerevolutionary America and an assistant dean at Yale. Readers will walk away with a fascinating double portrait of a slave family and their owners in 18th-century Connecticut. And they will see a version of slavery very different from the plantation iteration we’re used to: less violent, less ubiquitous, and one where slaves had a surprising number of opportunities to gain their own freedom.

Di Bonaventura’s achievement is to make the familiar seem strange, turning a topic we thought we knew so much about into something that feels new. Chronicling the port town of New London, Connecticut, she builds her story around the entwined families of Joshua Hempstead, a rags-to-riches shipbuilder, and Adam Jackson, the one and only slave he owned. If there is a broader point di Bonaventura is making by this juxtaposition, it seems to be that slavery and the racial stigmas it produced, even in colonial New England, slowly eroded the potential rewards for individual hard work. Though she could have made her argument more forcefully, the story she tells does expose the way that one American ritual—racism—impeded on another: work.

The white Hempstead, for instance, worked his way out of indentured servitude, the next step up from slavery. He was able to establish a profitable ship-building business, something racist attitudes prevented Adams’s father, the equally industrious John Jackson, from even being able to attempt. The life of John Jackson, who dominates the first half of the book, illustrates how race would quickly come to define prerevolutionary New England society in other ways.

Jackson, who came from the West Indies, was 18 when he was sold to the radical religious leader John Rogers in 1686. Rogers’s religious beliefs made him sympathetic to antislavery views, which were virtually unheard of at the time. Living among the sect Rogers founded (the “Rogerenes”) enabled Jackson to secure a greater level of autonomy than Connecticut’s mainstream Congregationalists would allow. Through Jackson’s persistent demands, Rogers agreed to eventually grant him his freedom. Yet ironically, di Bonaventura shows that the Rogerenes sometimes kept Africans enslaved in part to protect them from the more racist environment they faced once free. Even after Jackson earned his freedom, he chose to remain an indentured servant to Rogers rather than risk finding work as a wage laborer in some other town.

Jackson had another reason to stay with Rogers. His wife, Joan, was enslaved to a relative of Rogers’s, and lived nearby. She remained a slave her entire life, and when she was sold in 1714, Jackson, with help from Rogers, had the audacity to steal her back. That feat landed Jackson in court, where di Bonaventura, through impressive research, was able to find one of the few traces of him. It’s a rare moment when we hear the voice of a colonial New England slave: “She was taken away from me wrongfully,” Jackson said to the jury. For a black man to fight for his wife like that was, di Bonaventura points out, “nothing short of astonishing.”

Yet Jackson lost the case, and Joan was ultimately sold off to a place unknown. But Jackson stayed in New London until his death in 1737. That’s because his son Adam, who was not owned by Rogers but by Joan’s master, was sold when he was 27 to Joshua Hempstead, the master shipwright who lived nearby. The only information we have of Adam comes from Hempstead’s diary, which he wrote in for nearly five decades and is a source few colonial scholars have studied. The diary propelled di Bonaventura to write For Adam’s Sake, especially after she noticed the frequent mention of a servant named Adam. We only meet him in the last third of the book, which is not a problem in itself: slaves left precious few documents, the lifeblood of historians, and thus di Bonaventura is limited in how much she can say. Adam was treated well by Hempstead, and the two grew old together. Hempstead died in 1758, and two years later Adam Jackson’s name appeared on the New London tax rolls—as a free man. He likely died in 1764.

The scant information we get about Adam is revealing, however, though perhaps not for a reason di Bonaventura would like to dwell on. Di Bonaventura is at pains to prove that slavery was, though limited in the North, important in certain areas. But reading her story, you begin to think just the opposite. Slavery seems pretty inconsequential to New England society. Take the fact that Hempstead was nearly 50 when he bought Adam, who was also the only slave he ever owned. None of Hempstead’s wealth depended on slave labor. To a colonial New Englander, slaves were basically luxury items. They cooked, cleaned, perhaps helped maintain small farms, but no one had more than a few slaves. By contrast, the colonial South had become dependent on slaves. By the mid-18th century, slaves in Virginia made up nearly 40 percent of the population. In prerevolutionary New England at the time, they were just 3 percent. As the historian Ira Berlin put it, the South had become a “slave society,” one where slavery defined all aspects of the political, economic, and social order. But the North was a “society with slaves,” a place where slavery was marginal.

It could be argued, as some scholars do, that slavery actually was important to northern colonies, but not in the way that interests di Bonaventura. The northern colonies were only one part of a much larger British empire, and the empire’s wealth came mainly from the slave-based sugar colonies in the Caribbean. The North needed the sugar colonies as a market for the limited goods they produced: dried fish, meat, small produce. In effect, the sugar colonies subsidized the northern ones. Di Bonaventura mentions this dependency only in passing. Had she given us more context, we would have seen that slavery was critical to men like Joshua Hempstead.

Di Bonaventura is writing in a particular historical mode, “microhistory,” which is perhaps reason to cut her some slack. The goal of microhistory is to show how large historical abstractions—slavery, racism, economics—affect personal lives. In this she comes close to hitting the mark. Slavery may have mattered to prerevolutionary New England in ways that her book does not account for, but she illustrates how it was a noxious institution no matter its regional variation. It corroded the lives of the enslaved, their owners, and the society that supported them.