By the time Cambridge University spokesman Tim Holt was able to issue a statement denying my story early on Wednesday afternoon, it had already taken on a life of its own. The news that Professor Stephen Hawking, author of A Brief History of Time and Britain’s most famous physicist, was canceling his headline appearance at a conference hosted by Israeli President Shimon Peres in solidarity with the Palestinian academic boycott had swept the Web and percolated through the blogosphere.

My original exclusive on the website of the Guardian newspaper had racked up a massive 60,000 Facebook shares in a single morning, and the story was dominating radio news headlines and Web talkbacks across Israel.But it wasn’t true. I sat and stared at the terse Cambridge University statement and wondered whether this was the worst moment in my career as a professional reporter. Apparently, I had got the story—my biggest story to date—completely wrong. “Professor Hawking will not be attending the conference in Israel in June for health reasons—his doctors have advised against him flying,” said the university.

Twelve hours earlier, I had been told a very different version by officials at the British Committee for the Universities of Palestine (BRICUP). They had published a brief note on Tuesday evening with, they said, the approval of Hawking’s personal assistant announcing his withdrawal from the fifth Facing Tomorrow Presidential Conference. They told me that he had written a brief letter to the Israeli president changing his mind and making his reasons clear in terms that BRICUP described as “his independent decision to respect the boycott, based upon his knowledge of Palestine, and on the unanimous advice of his own academic contacts there.”

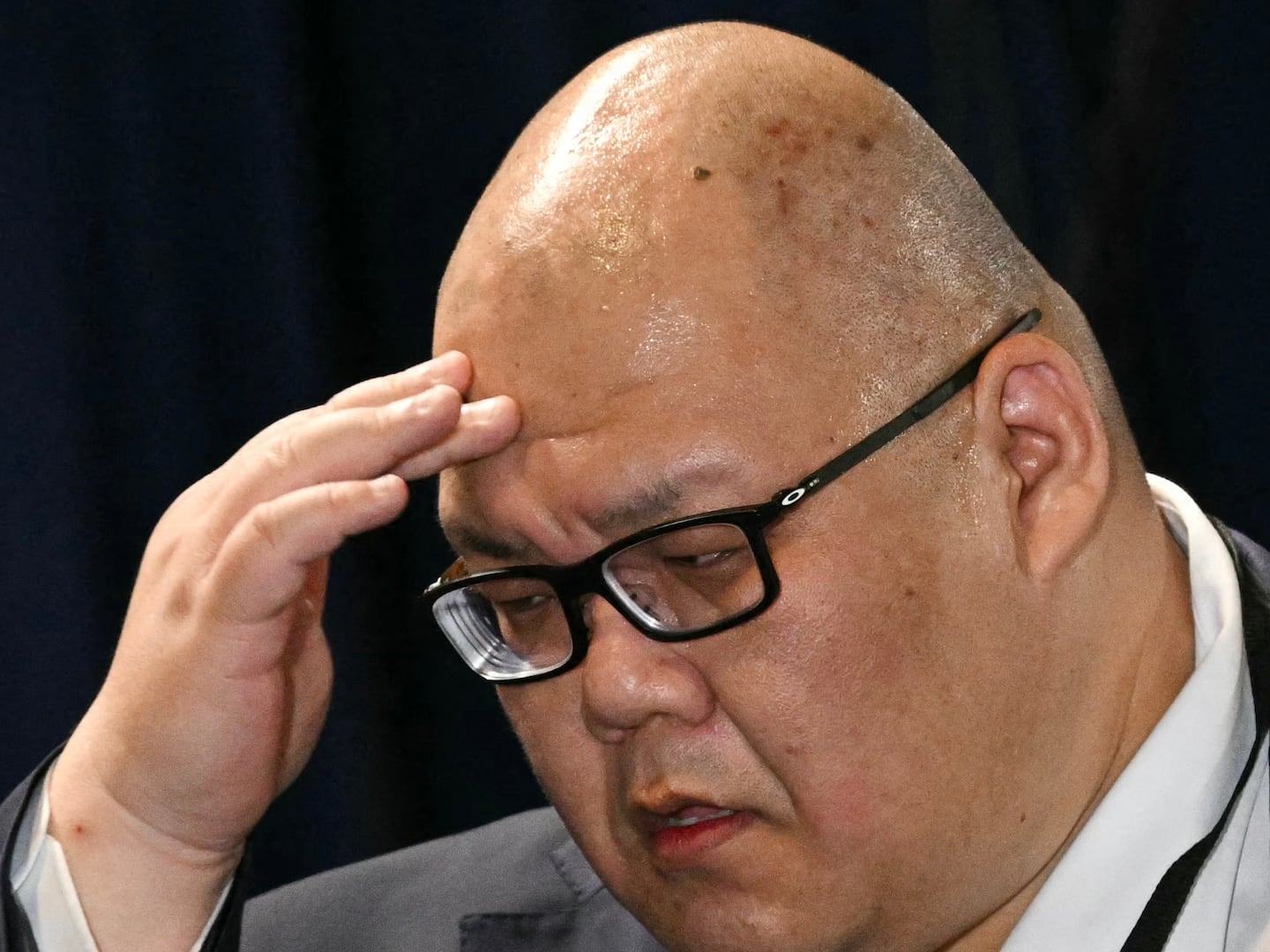

Early on Wednesday morning, conference chairman Israel Maimon issued a furious statement berating Hawking’s about-turn.

"The use of an academic boycott against Israel is outrageous and improper, particularly for those to whom the spirit of liberty is the basis of the human and academic mission. Israel is a democracy in which everyone can express their opinion, whatever it may be. A boycott decision is incompatible with open democratic discourse," Maimon fumed.

The dismay in Jerusalem was matched by jubilation among boycott supporters abroad. This year has seen some notable victories for the pro-Palestine boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement. In April the Teachers' Union of Ireland became the first lecturers' association in Europe to call for an academic boycott of Israel, and in the United States members of the Association for Asian American Studies voted to support a boycott, the first national academic group there to do so.

By participating in the boycott, Hawking was joining a small but growing list of British personalities who have turned down invitations to visit Israel, including Elvis Costello, Roger Waters, Brian Eno, Annie Lennox, and Mike Leigh.

Except that he wasn’t, according to Tim Holt at Cambridge University. Hawking, 71, has been suffering from the debilitating motor neuron disease ALS for half a century. He is paralyzed, breathes through a ventilator, and communicates via a sophisticated computer. Now his health was deteriorating further, and I had become a willing idiot helping the BDS opportunists make political capital from his disability.

I fired off some urgent emails and attacked the phone, hoping to wring an explanation from the BDS people that would salvage my reputation and the hope of working for the Guardian—or anyone—ever again.

Their response was as stunning as Tim Holt’s statement had been an hour earlier.

“It’s a pack of lies,” they told me.

“Sure,” I replied, as I watched my story being shredded on the Twitter feed scrolling down the screen like a leg of raw meat into a mincer. I was being accused of creating a “farce” based on “lies” and “bullshit.”

“There’s proof,” they told me. “Written proof.”

I switched off Twitter and started working the phones to London, Cambridge, and Jerusalem. Soon, I had the proof both to resurrect my battered story and to surrender my place in the dunce’s corner to the Cambridge University spokesman.

There was an email exchange showing quite clearly that Hawking’s personal assistant and Tim Holt had both approved the BRICUP announcement that sparked my interest on Tuesday night. And there was Hawking’s letter, sent to the conference organizers on May 3 on Cambridge University letterhead, setting out clearly his reasons for pulling out: no health issues, all boycott. It had been copied to several other people. One of them was kind enough to share it with me.

“I accepted the invitation to the Presidential Conference with the intention that this would not only allow me to express my opinion on the prospects for a Peace Settlement but also because it would allow me to lecture on the West Bank,” wrote Hawking. “However, I have received a number of emails from Palestinian academics. They are unanimous that I should respect the boycott. In view of this, I must withdraw from the conference. Had I attended, I would have stated my opinion that the policy of the present Israeli government is likely to lead to disaster.”

Confronted with the two pieces of evidence, the Cambridge University spokesman realized he had been caught in a lie. Over the phone, he apologized to me and admitted the previous statement about Hawking’s health had been inaccurate.

“You were right,” he said. “Stephen did send a letter on Friday to the Israeli Presidential office saying that he would respect the boycott. Your sources were correct and you have my apologies. I was misinformed.”

An hour later, he released a public statement that said almost (but not quite) the same thing.

So we were able to report on Wednesday that Hawking had indeed joined the boycott in what must be one of the BDS campaign's biggest victories.

What I’d like to know—apart from whether any of my mealy-mouthed Twitter critics are going to retract their insults—is what effect Hawking’s decision will have on Israel’s leaders. Will they hunker down behind a security wall of denial, or will someone, somewhere in Jerusalem ask why a man of Hawking’s standing, who has visited Israel four times in the past and was willing to come again despite his age and ill-health, has become so alienated, so quickly, from a country he previously admired so much?