You practiced corporate law, which doesn’t sound quite as exciting as writing bestselling books and giving dynamic public lectures. How did you make the jump, and if it’s not a weird question, is there anything you miss about the corporate law world?You will find this hard to believe, but I’ve never laughed as much as I did when I was a corporate lawyer. When you’re working 16 hours a day for months at a time, you get punchy. Everything and everyone seems hilarious.

But really, I was the least likely lawyer on earth. I feel incredibly lucky to do what I’m doing now. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was 4.

The TED talks have become a real springboard for distilled scientific ideas, transposed into an approachable, entertaining format, much like your book. You were also a popular TED speaker. How did the TED experience help and influence you? Could you describe what it’s like to be a speaker at the main TED event?Oh, I was terrified. I’ve always been afraid of public speaking, so presenting on the TED stage required the slaying of a great personal dragon. But, you know, the job of dragons is to guard treasure chests. My prize was getting to share my ideas with millions of people via TED.com, through the primal art of oral storytelling. And ever since TED, I’ve had the chance to lecture around the world and don’t even feel that scared! A year ago I’d have said that was impossible.

One of my next projects is to create an online course in public speaking for introverts. I want people who are not spotlight seekers to realize that they don’t have to be natural speakers—they just need to have something to say and to learn a few techniques to help them say it. And the world needs to hear from its introverts. (If you want to hear more about the course, you can sign up for information at www.thepowerofintroverts.com.)

What is a distinctive habit or affectation of yours?I never go a day without dark chocolate.

What is your favorite item of clothing?The silver necklace I wore to my TED talk. My friend Hitomi brought it back for me from Laos. It had a pendant that looked like a house, which to me signifies warmth and happiness. Sadly, I’m speaking of this necklace in the past tense, because I brought it to London for my book tour and lost it at Heathrow. I guess it lives on forever in the TED video.

What are your thoughts on the Malcolm Gladwell-ification of science writing?I love Gladwell’s books, and the genre he created, and am annoyed by how fashionable it’s become to criticize him for being slick and not a “real” intellectual. I think that writers like Gladwell perform a service precisely because they’re not academics. They’re not too close to the research, so it’s easier for them to appreciate how fascinating it is.

When I started researching Quiet, I found so much amazing stuff that’s second nature to personality psychologists but utterly unknown to laypeople. (Did you know that introverts, who are more sensitive to stimuli than extroverts, will salivate more if you pour lemon juice on their tongues?) Academics, who’ve been studying this stuff since graduate school, can’t always see how remarkable it is. In fact, the more immersed I became in my subject, the more it started to seem like second nature to me, too. I had to go back and remember how awestruck I felt when I encountered it for the first time.

I do think there’s a tendency in the last five or 10 years for writers to use neuroscience in a reductive way, as if that’s the only or best way to understand human nature. And there’s a temptation to act as if we know more about the brain than we really do. But people are already starting to self-correct on this. So I think we’ll be OK.

What is guaranteed to make you cry?Oh, just about anything. I can’t stand the thought of parents losing their children, or vice versa. And the other day I listened to a song called “Hinach Yafah,” by the Idan Raichel Project, and wept because I was pretty sure I’d just glimpsed the divine. Or at least the profound yearning for it, which I think may be the same thing. Try it, you’ll see what I mean.

Was there a specific moment when you felt you had “made it” as an author?Yes. When I realized that I had a committed group of readers—kindred spirits, really—with whom I could share things. Whenever I read or hear something I love, I have a compulsion to tell everyone I know. When I listened to that song I just told you about, I immediately posted it on Facebook and Twitter, and people I’ve never met in person wrote to say how much it moved them too. I love that!

What do you need to have produced/completed in order to feel that you’ve had a productive writing day?I notice that most writers have quotas of some number of words per day. I envy this approach, because it seems so clean, but it has never worked for me. I often spend an entire day editing, restructuring a narrative, or researching. There are no new words on the paper, but it’s still progress. I think. It might also be a really elaborate way of procrastinating.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?You probably want to be a writer because books and words are a source of wonder to you. Make sure to keep it that way. Do not turn writing into a business or chore. It’s hard work, yes, but it should still be the thing you itch to do every day.

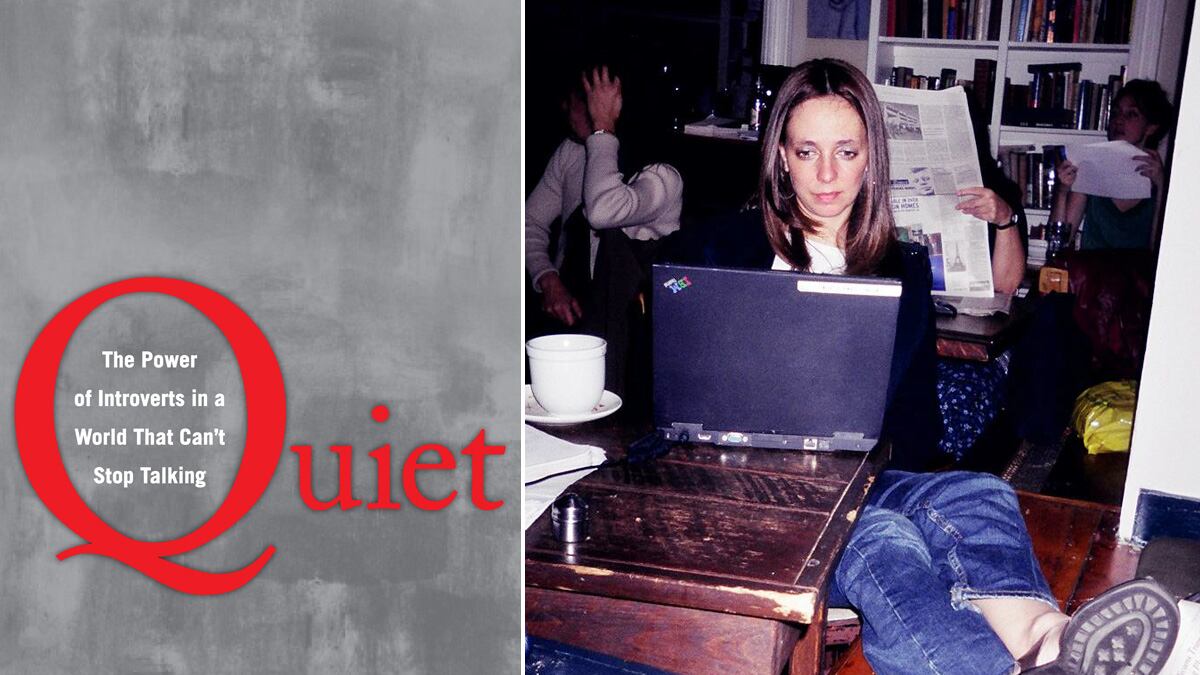

When I quit law and took up writing, at age 33, I told myself that it was OK if I didn’t publish anything until I was 75. That took the pressure off. I started a little consulting firm to pay the bills and spent the rest of my time at various cafés, working on my “hobby.” I’m actually not sure if I went to the cafés to write or wrote so I could sit around in cafés, which is my favorite activity. I wrote most of Quiet at a Greenwich Village café that drew writers from all over New York City and tragically no longer exists.

This interview has been edited and condensed.