For 11 days after the 9/11 anniversary assault on the U.S. diplomatic facility in Benghazi, top Obama administration officials told the public that the assault stemmed from a protest of an anti-Muslim YouTube video. That was the public line from the White House in the closing weeks of a presidential election season, but it was not the view of several State Department officials at the time or the U.S. personnel on the ground in Libya.

At a hearing Wednesday of the House Oversight and Government Reform committee on Benghazi, Trey Gowdy (R–South Carolina) read into the record an email from Beth Jones, the acting assistant secretary of State for Near East Affairs. The September 12 email—disclosed for the first time on Wednesday—said Jones had spoken to Libya’s ambassador to Washington, who said the attack was the work of former Gadhafi regime loyalists. Jones said she told the ambassador: “The group that conducted the attacks, Ansar al-Sharia, is affiliated with Islamic terrorists.”

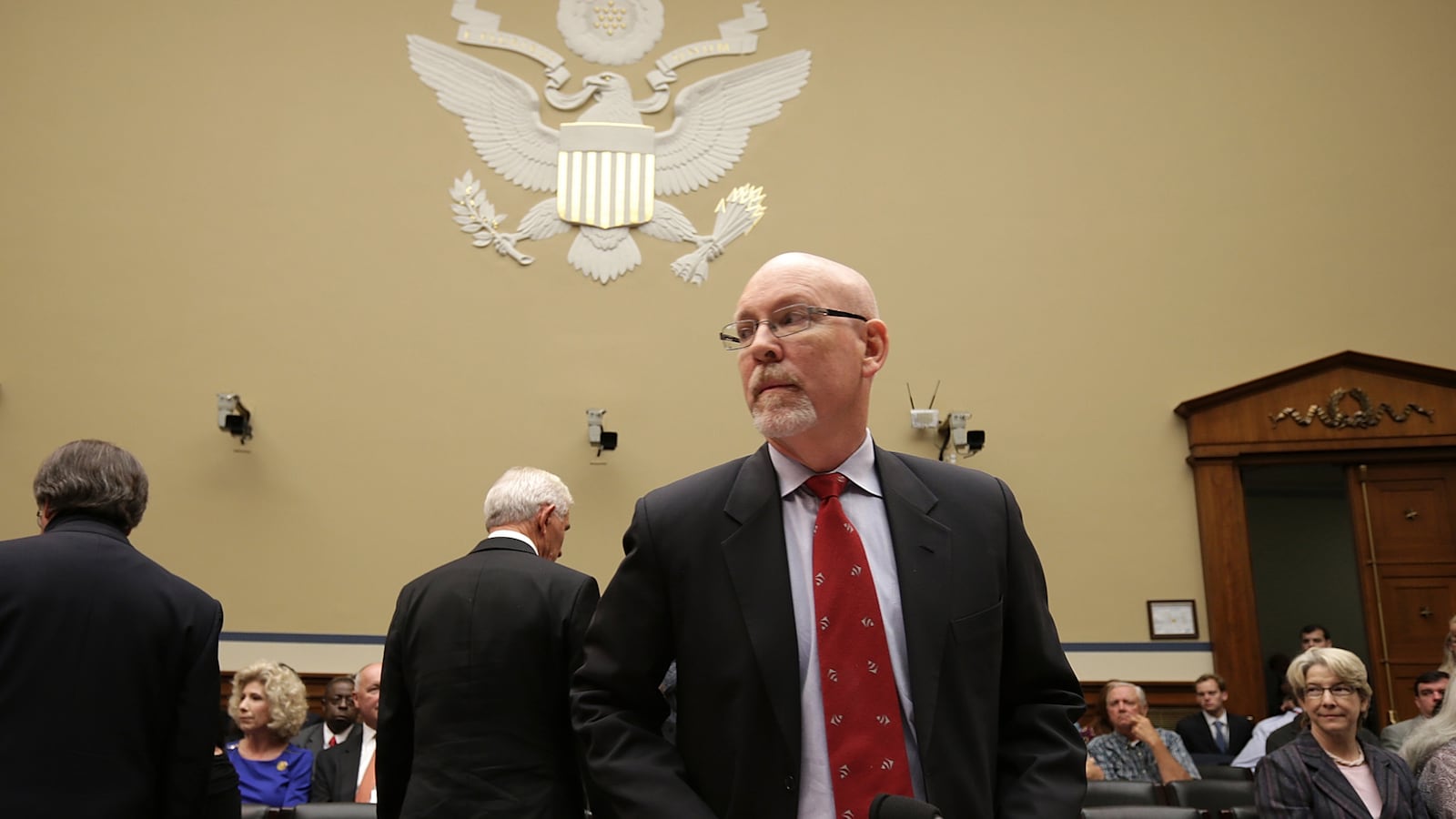

Jones was not the only one who viewed the attack as the work of terrorists. Gregory Hicks, the deputy chief of mission at the U.S. embassy in Tripoli at the time, said there were no reports from U.S. personnel in Libya that there was a demonstration. In often-dramatic testimony, Hicks provided new details of the attack in the evening of Benghazi. He said he had no doubt at the time the assault on the U.S. compound in Benghazi was a terrorist attack, noting that Ansar al-Sharia had claimed credit for the assault on its Twitter feed. Indeed, the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli believed it would be attacked next. Hicks said embassy personnel smashed hard drives, loaded weapons into armored vehicles, and that the 55 embassy employees in Tripoli that evening were gathered in a safe annex, all in anticipation of the attack.

In one of the most dramatic moments of the hearing, Hicks recounted what were likely some of the last words of Christopher Stevens, the U.S. ambassador who was killed in the initial assault on the diplomatic and intelligence compound in Libya’s second city. In a patchy phone call, Stevens told Hicks: “We’re under attack.”

Republicans drew blood on the issue of what Obama and his top advisers said about Benghazi after the attack. Senior State Department and intelligence officials have said since the fall that the statements from top U.S. officials in the days after the Benghazi attacks were based on the best intelligence at the time.

But the case that more could have been done on the evening of the attacks to prevent a second assault was murkier. That attack resulted in the deaths of Glenn Doherty and Tyrone Woods, two former Navy SEALs and CIA security contractors, who were killed by mortar attacks at a nearby CIA annex at around 5 a.m.

As The Daily Beast reported Monday, Hicks said he asked the U.S. defense attaché at the embassy about sending F-16 fighter jets stationed in Aviano Air Base in Italy. Hicks said he believed simply scrambling those jets would have scared off the attackers in the second wave. Hicks was told by the defense attaché that the jets could have arrived in Benghazi within two to three hours.

Earlier this year, Gen. Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said it would take 20 hours to send those jets to Libya. Former secretary of Defense Leon Panetta told Congress earlier this year no other military assets could have been sent in time to Benghazi on the night of the attack. “This was pure and simple a problem of distance and time,” Panetta said.

Hicks also said he wanted to send a second special-operations team of four men to Benghazi at 6 a.m. on September 12. But the team would have left Tripoli nearly an hour after the second wave of attacks began. Nonetheless, Hicks said, he did not know why the team was told to stand down. He thought it was prudent to send the team because he said U.S. personnel were still in danger and the remaining security personnel in Benghazi were exhausted. “People in Benghazi had been fighting all night,” Hicks said. “We wanted to make sure the airport was secure for their withdrawal.”

Mark Thompson, the deputy coordinator for operations at the State Department’s bureau of counter-terrorism during the Benghazi attacks, testified that the Foreign Emergency Support Team (FEST)—a special unit comprised of special-operations officers, FBI officers and diplomatic security personnel—was not deployed on the evening of the attacks.

“I alerted my leadership indicating that we needed to go forward and consider the deployment of the Foreign Emergency Support Team,” Thompson said. He added that he was told that meetings had already taken place. “I was told this was not the right time to deploy the team.”

In an email sent to reporters the night before the hearing, the State Department provided a quote from Thompson’s boss at the time, Daniel Benjamin, who was the U.S. assistant secretary of State for counterterrorism, that defended the decision not to send the team. “The question of deployment was posed early, and the department decided against such a deployment,” Benjamin said. “In my view, it was appropriate to pose the question, and the decision was also the correct one. There is nothing automatic about a FEST deployment, and in some circumstances, a deployment could well be counterproductive.”