From a prison camp in Egypt’s western desert in 1963, a young dissident, Sonallah Ibrahim, recorded in his diaries that he “must write about Cairo after studying her neighborhood by neighborhood, her classes, her evolution.” A year later he was out of prison, having served five years of a seven-year sentence for being a Communist. He smuggled his diaries back to Cairo by copying them onto cigarette rolling papers. But Egypt’s capital was its own kind of prison, as the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser kept him under house arrest from dusk until dawn. He tried working on a novel of his childhood, but focused instead on a bleak, honest record of his days in a city browbeaten by Nasser’s omnipresent police. “The new reality consumed me,” Ibrahim later wrote, and so his work had to engage “the struggle against imperialism, the effort to build socialism, and all the difficulties these efforts brought in their train: terror, torture, prison, death, personal misery.”

The outcome was his first novel, That Smell, published and quickly banned in 1966. Its nameless narrator is a recently released political prisoner and writer living under house arrest. He roams Cairo when he’s not checking in with a police officer every night, visits old friends and family, smokes, spies on his neighbors, and otherwise fails at writing and sleeping with a prostitute. The book, devoid of much plot, captures the debilitating effects of police repression under Nasser, but also anticipates a mood of decline and looming disaster brought by Egypt’s humiliating defeat in the 1967 war with Israel, followed by Nasser’s death in 1970. State censors decried Ibrahim’s portrait of a listless Egyptian society, singling out its few brief sexual scenes. At a Ministry of Information interrogation, a zealous officer demanded to know why Ibrahim’s narrator fails to sleep with a prostitute. “Is the hero impotent?” he asked, taking more offense to the perceived insult to Egyptian masculinity and, it seems, national prowess, than to the book’s portrayal of torture.

Ibrahim suspected these gripes were just cover for the regime’s actual objection to the book’s subversive politics, what Robyn Creswell, the translator of a new edition of That Smell, calls “the feeling of life after politics,” when dreams of revolution, Arab unity, and post-colonial independence stalled under Nasser’s authoritarianism. The regime-controlled press panned Ibrahim’s radically pared-down writing style, which was nothing like the florid prose of so much Arabic literature up to the 1960s. Creswell describes this style as “defined by all the things it leaves out: metaphors, adjectives, authorial commentary” – even paragraph breaks. (Its first English translation, published in 1971, did away with this radically minimalist style; Creswell’s superb new translation revives the shock and simplicity of the original Arabic.) Ibrahim’s matter-of-fact portrayal of sex and masturbation prompted one critic to decry That Smell’s “lowness, its vulgarity.” Twenty years later, when an unedited version of the book finally appeared in Egypt, Ibrahim replied to the critic in the introduction: “Wasn’t a bit of ugliness necessary to expose an equivalent ugliness in ‘physiological’ acts like beating an unarmed man to death?”

Such bold, uncompromising writing became Ibrahim’s hallmark. In seven other novels, he has catalogued, often with acid wit and sarcasm, social malaise, cultural stagnation, and torment under successive autocrats in Egypt: Nasser, Anwar Sadat, and Hosni Mubarak, who was deposed in eighteen euphoric days of protest in 2011. Two of Ibrahim’s greatest books–The Committee (1981) and Zaat (1992), both lambaste Egypt’s realignment with America under Sadat and Mubarak and the simultaneous opening of its economy to Western markets. In Ibrahim’s stories, consumerism and globalization only enrich the elite, turning bureaucrats and officers into corrupt middlemen and tycoons, while distracting everyone else from the realities of dictatorship. The Committee, in particular, is a kind of Kafka tale, if Kafka explored how state censorship demeans, then consumes writers and artists. It would be a mistake to read That Smell as a relic, just a portrait of torture and tedium under Nasser. Even after the euphoria of toppling Mubarak, the structures of the regime built under Nasser remain intact, from aggressive police powers to the military’s unchecked economic and political privileges. For many Egyptians, the on-going, if sputtering revolution is against this entrenched regime and its half-century of political, military, and police authority–not against one dictator alone.

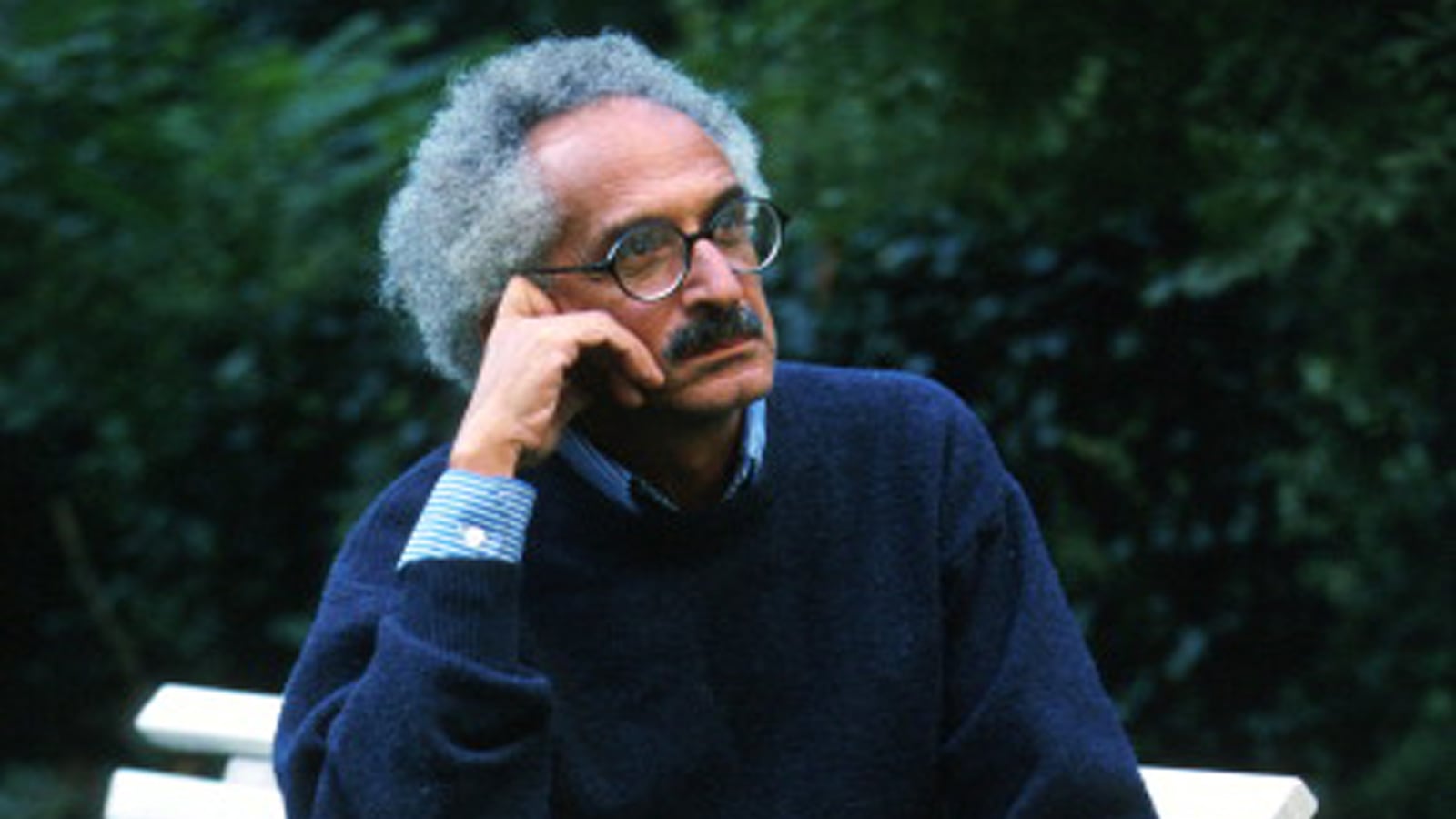

In 2003 the Egyptian government unexpectedly bestowed a major writing prize on Ibrahim. At the ceremony, in front of ministers and a host of cultural figures close to the regime, he lit into the state of Mubarak’s Egypt: “We no longer have any theater, cinema, scientific research, or education. Instead, we have festivals and the lies of television … Corruption and robbery are everywhere, but whoever speaks out is interrogated, beaten, and tortured.” He rejected the prize, along with the sizable prize money, “for it was awarded by a government that, in my opinion, lacks the credibility to bestow it.” Ibrahim exited the hall that night to silent shock from the regime’s apparatchiks and wild applause from the young writers in the audience. Protected by his fame and stature, he avoided another stint in prison. A decade later, Ibrahim remains the political conscience of Egyptian letters.

Creswell’s edited selection of Ibrahim’s diaries, Notes from Prison, included in the same volume, reveal the roots of this sharp, uncompromising political mind. Here is a young, ideological but principled writer–“I am a Communist first, a writer after that,” he declares–studying how his stripped down literary form, modeled in particular on Ernest Hemingway, could speak political truth. But the diaries also reveal Ibrahim’s conflicted relationship with Nasser’s legacy of political dictatorship. Ibrahim’s contradiction, which Creswell highlights in his introduction, is that he still believes in the leadership and ideology of the leader who sent him to prison, not unlike many Soviet intellectuals who were locked away for their politics but still supported Stalin. “It is from the Soviet writers that Ibrahim gets his obsession with ‘telling the truth,’” Creswell writes. “For the Soviets, this meant telling the truth about Stalin and the Gulag. For Ibrahim, it meant telling the truth about Nasserism.”

Among the influential Soviets was the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, whose memoirs Ibrahim read in 1963, excerpted in an issue of the French magazine L’Express. Ibrahim, in his Notes, referenced a Yevtushenko passage about jailed Bolsheviks: “They never accepted that [Stalin] had personally ordered their treatment. Some of them, after being tortured, traced the words ‘Long Live Stalin’ in their own blood on the walls of their prison.” The passage is accompanied by a footnote, later added by Ibrahim, in which he asks himself, “Was I aware, when I copied these lines, of the extent to which they described our own situation?”