Robert Langdon, the long-suffering but durable Harvard professor who is the protagonist in The Da Vinci Code and several other Dan Brown novels, has a thing for Harris Tweed. No, make that passion, verging on obsession. At one point in Brown’s new novel, Inferno, Langdon discovers another character sewing a secret pocket into his jacket. “The professor stopped and stared as if she had defaced the Mona Lisa,” Brown writes. “You sliced into the lining of my Harris Tweed?” Langdon erupts in what may his most emotional moment in the entire novel.

So it comes as something of a surprise, upon meeting Brown in the flesh, to see that he’s not wearing tweed but rather just an ordinary cloth jacket—moreoever, he’s jolly and animated, not grim or paranoid, and nobody’s chasing him. It is the first of several clues that Brown and his hero are not the same person, a point that the author takes pains to make at several points in the subsequent interview, conducted Monday at his publisher’s Manhattan offices—the day before Inferno went on sale in stores. (It was already No. 1 at Amazon, where it’s the most preordered book of the year, not surprising for an author whose books sell in the seven-zero stratosphere—The Da Vinci Code alone has sold more than 80 million copies worldwide.)

What most alarms Brown, he says, “is that whatever is written in one of my books, some readers will assign to me as my ideology. So you get some maniac that’s cast as a villain who’s saying stuff that’s nuts, and they say, ‘Brown says!’ No, no, no, Brown didn’t say that. A character said that. There are people who, apparently misunderstanding the concept of fiction, will take things out of context and assign them to me, whether out of ignorance or malice, I don’t know.”

(Before he gets around to distancing himself from Langdon’s taste in clothes, I decide to drop the whole Harris Tweed question.)

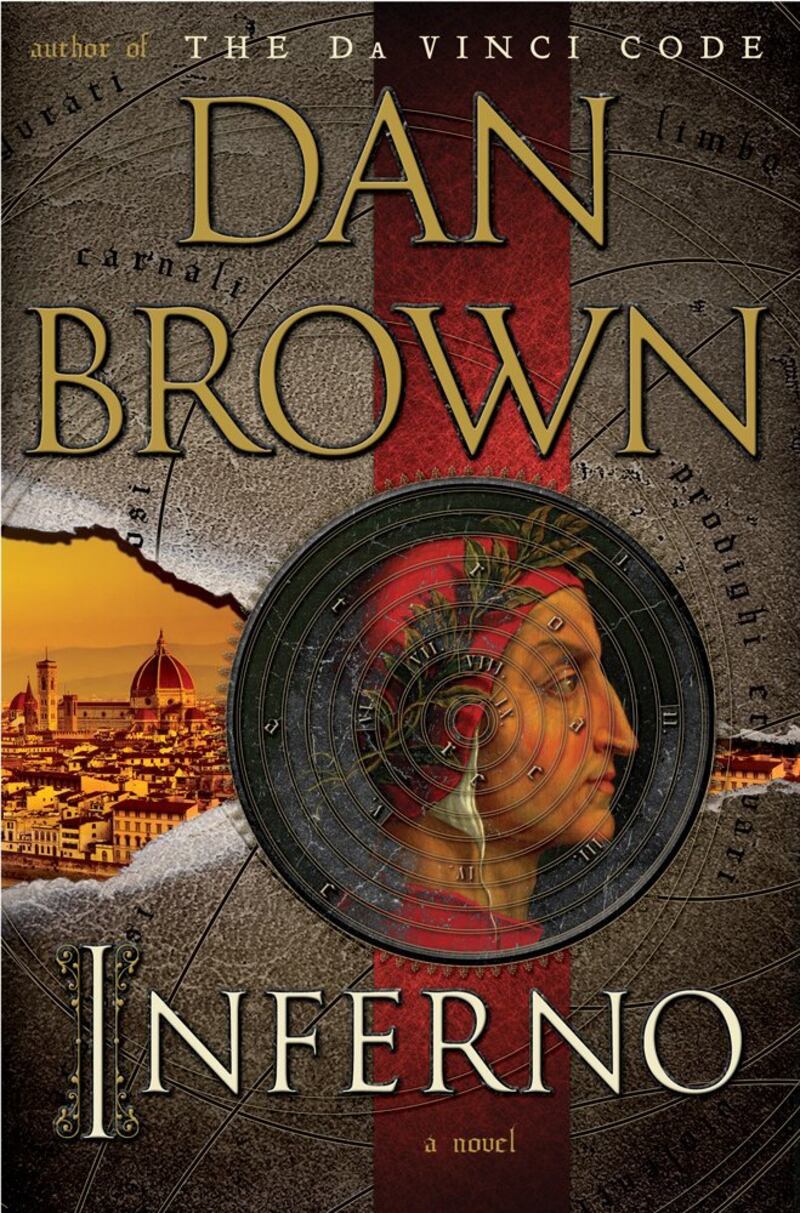

Where Langdon and his 48-year-old creator do overlap is in their shared passion for knowledge and the conjoined passion to share this knowledge with as many people as possible. Like its predecessors, Inferno combines a fascination with ancient symbols, codes, and secrets with an equal fascination with a contemporary dilemma. This time around the ancient stuff is supplied by Dante’s The Divine Comedy, particularly by part one, Inferno, the part where Dante tours hell. The contemporary issue at hand is population growth.

(Dante’s Inferno, it’s worth noting, is also doing quite well on Amazon, perhaps because Brown has generated new interest in a classic, or maybe just because readers are ordering Dante thinking they’re ordering a Dan Brown book.)

The hectic plot involves lots of people chasing Langdon and a hot female physician (whose 200-plus IQ nicely compliments Langdon’s photographic memory) all over Florence and then Venice, before everyone winds up in Istanbul after many double crosses, triple crosses, and maybe even quadruple crosses (I lost count). Langdon suspects that a mad scientist may be unleashing a new plague upon the world as his way of controlling the its exploding population before civilization succumbs. Fortunately for Langdon, the hubristic scientist is also a Dante fan, and he’s left lots of clues that only an art professor and symbol expert like Langdon is equipped to understand.

Characters really do say things like, “We’re running out of time!” And Langdon literally strokes his chin at one point when he’s thinking. But if it isn’t Proust, you can’t say it’s ever dull. Brown may not be a great prose stylist, but he knows how to push our paranoia buttons, and he knows how to make a plot clip along. Inferno pegs the odometer needle into the red at the outset and stays there for nearly 500 pages.

What keeps you turning those pages, though—and what ultimately makes this by far Brown’s best book—isn’t the plot so much as the intellectual energy behind it. For readers who like to feel they’re learning something, even when they’re reading fiction (and that’s a group that includes the author himself), Brown’s books are the ticket. Think of them as extremely creative interdisciplinary lectures by your most inspired professor—but with guns and car chases—and you’ll have a fine time.

“I’ve known that I was going to write about Dante for at least 10 years,” says Brown, who taught high school before committing to writing full time in the ’90s. “Writing Angels and Demons and The Da Vinci Code and immersed in church history, I came to understand the effect and the influence that Dante had on our modern Christian vision of hell. The Bible talked about hell in kind of ethereal terms. Greek mythology talks about hell in slightly more concrete terms, with monsters in certain regions. But then along comes Dante with this codified, structured vision of this terrifying afterlife. That’s our vision of hell. The underworld came from him.”

Brown is keenly aware that the potent strain of paranoia coursing through modern culture is one reason so many people snap up his novels, with their star chambers and puppet masters and explanations for everything. “The human mind craves order,” he says. “People want to believe that someone is driving the bus, which is why when someone dies, we want to hear that it was God’s plan. It’s why when something bad happens in the world, we come up with conspiracy theories to say why it happened. We don’t like thinking things are random.” That said, he refuses to plead guilty to stoking the bonfires of paranoia: “I may be naive, it may be self-serving, but I would argue that I’m on the other side, trying to bring a little sanity to the masses,” he says. “I write fiction, and I don’t put my feelings or opinions out there. At the end of these books, I don’t really come out and say, this is the way it is. I say, why don’t you think about this.”

Brown says his greatest joy would be to find that readers of Inferno were avidly discussing Dante. “I’m always trying to make these ancient ideas feel relevant and be relevant to the real world. In researching Inferno, some of Dante’s brutal vision of crowded realms of souls tormented and starving felt like some of the Malthusian visions of the future. And I came up with this idea of a villain who’s both a Dante fanatic and also a Malthusian, who essentially believes that Dante isn’t history, he’s prophecy. That’s the moment the two threads clicked, and I realized that this book would incorporate Dante and overpopulation.”

And just maybe there was some he-reminds-me-of-me stuff going on, too. Describing The Divine Comedy in Inferno, Brown writes that “it brilliantly fused religion, history, politics, philosophy, and social commentary in a tapestry of fiction that, while erudite, remained wholly accessible to the masses.” Dante, the Dan Brown of the 13th century!

Brown is so invested in the ideas undergirding Inferno that, in a weak moment, the notoriously press-shy author agreed to do several days of interviews to promote his novel, a decision he’s already regretting. Reporters, he’s found, aren’t clamoring to learn more about Dante or even this retiring writer’s work habits (at the keyboard every day by 4 a.m., writing until midday, seven days a week, even on Christmas; throwing away 10 pages for every one he keeps). No, since he let slip in one of his first interviews that he uses gravity boots to help himself concentrate, that’s all he gets asked about. “It’s one of those things I wish I’d never mentioned,” he admits with a rueful laugh. Then, before his interviewer can toss another question, he throws up his hands and says, “There are no other strange things that I do!”