From the start of his writing career in the 1950s, history (and historical myth) would always be present for Carlos Fuentes, as he argued it was for his nation, Mexico. But that wasn't just a literary conceit. Fuentes liked to point out that to scratch the surface of Mexico City was to reveal the presence of the past. Indeed, to change trains at the Pino Suárez subway station, a passenger must circumambulate an Aztec pyramid that was excavated during the stop's construction. The past was present in Mexico, he would say, to a greater extent than in the United States. This may be true. We didn't recognize our own Native pyramids—the Cahokia Mounds—until the 1960s, by which time all those in St. Louis, the Mound City, had been long leveled. Despite the Spanish names of our Western states and towns, we forget that they were part of Mexico until 1848 (1836, for Texas). Mexicans are less likely to forget. Fuentes worried about the tendency to forget, the danger of replacing history with nostalgia, because amnesiac societies could drift into fascisms.

Not just past and present, but also the poor, the middle class, and the rich, and the natives, creoles, and Europeans, collided in the Mexico City of Fuentes's first novel, 1958's Where the Air Is Clear. He was the great explicator of Mexico City, as Dickens had been with London and Balzac for Paris. Fuentes wrote beautifully about Mexico City, with love and anger. In a recent work, Vlad, a man stuck in traffic, on his way to rescue his family, looks at the exotic billboards high above the poverty and corruption on the street.

I had never before been so tortured by the slowness of the Mexico City traffic; the irritability of the drivers; the sadness of begging mothers carrying children in their shawls and extending their callused hands; the awfulness of the crippled and the blind asking for alms; the melancholy of the children in clown costumes trying to entertain with their painted faces and the little balls they juggled; the insolence and obscene bungling of the pot-bellied police officers leaning against their motorcycles at strategic highway entrances and exits to collect their bite-size bribes; the insolent pathways cleared for the powerful people in their bulletproof limousines; the desperate, absent gaze of old people unsteadily crossing side streets without looking where they were going, white-haired, nut-faced men and women resigned to die the way they lived; the giant billboards advertising an imaginary world of bras and underpants covering small swaths of perfect bodies with white skin and blonde hair, high-priced shops selling luxury and enchanted vacations in promised paradises.

In a sentence about a man who fears he can't move, we are given a tour of 21st-century Mexico City life, including its frustration.

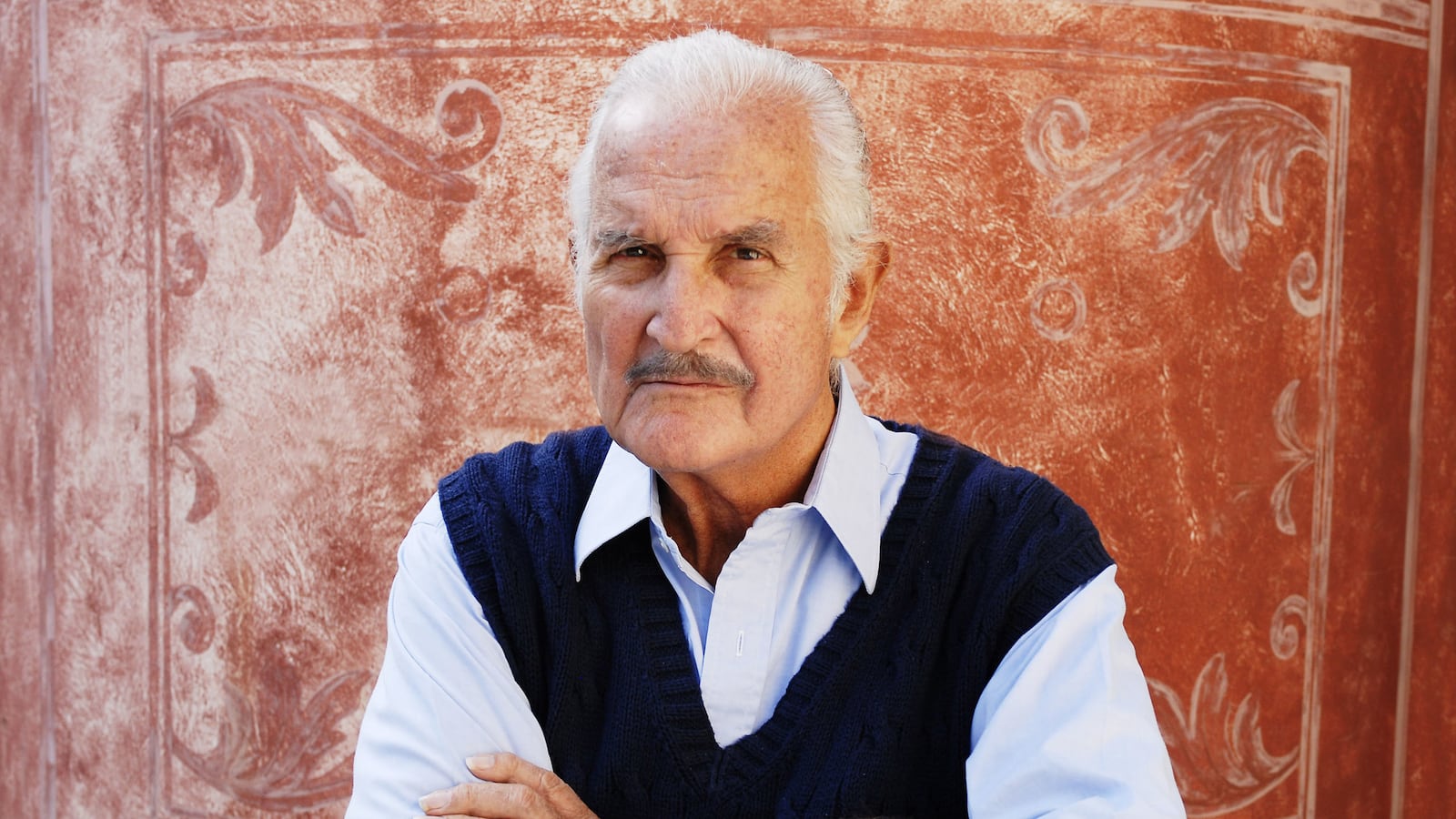

Carlos Fuentes died a year ago today at age 83 in Mexico City. If he were here now, he would have much to say about life and literature. While condemning the Mexican drug trade—as he did in two novels—he might point out that without illegal demand from north of the border, there would be no violence. When we debate Mexicans’ right to live in the U.S., he might remind us that much of the land they live in used to be part of Mexico. The Mexican war, which so annoyed Illinois Congressman Abraham Lincoln and which landed a protesting Henry David Thoreau in prison is something we now take for granted. In that light, immigration is a repeat of the Reconquest, when Ferdinand and Isabella took Spain back for Catholicism. He might remind us, for the good of our own humanity, to imagine Mexicans’ point of view. Fuentes had a stomach ulcer that caused him to spit blood, and he bled out while waiting for an ambulance caught in traffic in his beloved Mexico City. He died in a taxi on the way to the hospital. But we still have his books.

I miss him. I took some of Fuentes’s college classes in the 1980s. He had on the tip of his tongue great swaths of European, U.S., and Latin American literature, world cinema, and art history. I spent a lifetime trying to catch up with all the books he told us to read, not to mention his dozen collections of essay, plays, screenplays, and 30-odd works of fiction. His most recent novel was published in Spain and Latin America: Friedrich on the Balcony, an incisive portrait of a mashup revolution that includes the French and the Mexican and elements of those of 1848, and the American. Between chapters, Fuentes and Friedrich (that's Nietzsche, who by virtue of eternal return, is back for the day) discuss the revolution and the intrigues of its main players.

Carlos Fuentes was always happy to hear about an old student’s progress. A former ambassador to France, he was very suave and attentive. He could also combine these qualities with shtick. In 2011 I attended his last Emersonian lecture at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan with my parents, while a blizzard was gathering outside. Afterward, I introduced him to my mother, whom he told what a beautiful woman she was, then asked in mock seriousness, why she had such an ugly son? We were already charmed and laughing at once when I introduced my father. Now I understand, Fuentes kidded, why he's so ugly.

In my old notebooks, I am struck by Fuentes's consistency of vision. Much great art, he taught, was a call to break free from captivity and into the world. In my notes on the Luis Buñuel movie Él, which I remember as the story of an Othello who, thanks to his paranoia, needs no Iago to make him a jealous beast, jealousy isn't even mentioned. Instead Fuentes followed the man he called the 40-year-old virgin from the time he officiates at a church service and develops desire to the time he shuts himself away from the world in a monastery. In between he becomes jealous and violent. Basically, the class on Él was about being able to distinguish the internal from the external world, from which we should learn. Fuentes interpreted the narrative as an illustration of the difference between loving the world and shutting the world out. Fuentes was a man who loved the world. One of my more comprehensible notes from that class: "Love + Need = Civilization." What a strange, plaintive philosophy for someone whose profession involved sitting alone most of the day: love the world.