For more than 22 years, Debbie Milke has sat on Arizona’s death row, convicted of killing her only child. Known locally as Death Row Debbie, Milke and her lawyers have argued for years that she was the victim of a crooked cop with a history of lying under oath. Finally, the courts took notice. And Death Row Debbie could be free in a matter of days.

Milke’s story began on Dec. 2, 1989 when her four-year-oldboy, Christopher, said goodbye to his mother and climbed into the car withtheir roommate, a head-injured, PTSD-haunted Vietnam veteran named JamesStyers. Milke had told Christopher that Styers would drive him to a local mallto visit Santa Claus.

Debbie and Christopher Milke had moved in with Styers some months before, when the 25-year-old divorced mother and insurance-company secretary had no place else to go. She'd fought with her family and ex-in-laws, and was virtually homeless.

She frequently entrusted Christopher to Styers, but he washardly an ideal babysitter. His PTSD stemmed in large part from an incidentduring the war when he shot and killed a young Vietnamese boy who had climbedonto a truck transporting Styers and other Marines in Vietnam, according tocourt documents. In his 1985 personal journal, now part of court records,Styers wrote: "Losing sleep because of dreams in Viet-Nam [sic] Seeingkids including my own and wondering if I'm going to do something to hurt them,and remembering the ones I had to kill."

With Christopher in the car, Styers picked up his good friend Roger Scott. The two men did not take Christopher to see Santa. Instead, they drove Christopher into the desert, where Styers emptied three bullets into the boy's head.

Styers and Scott told police Christopher disappeared at the mall. But a day later, Scott fell apart and led officers to the child's corpse. Scott, police later said, implicated Debbie Milke in the murder scheme.

That same day, Styers and Milke confessed to the murder, according to police. The Phoenix police department's star interrogator, Det. Armando Saldate Jr., had been called in on his day off to separately question the three. In a matter of hours, Saldate had secured a speedy resolution to the horrific high-profile holiday crime.

In court, prosecutors contended that Scott had volunteered to drive the car as part of a plot engineered by Styers and Milke to slaughter Christopher for a $5,000 insurance policy.

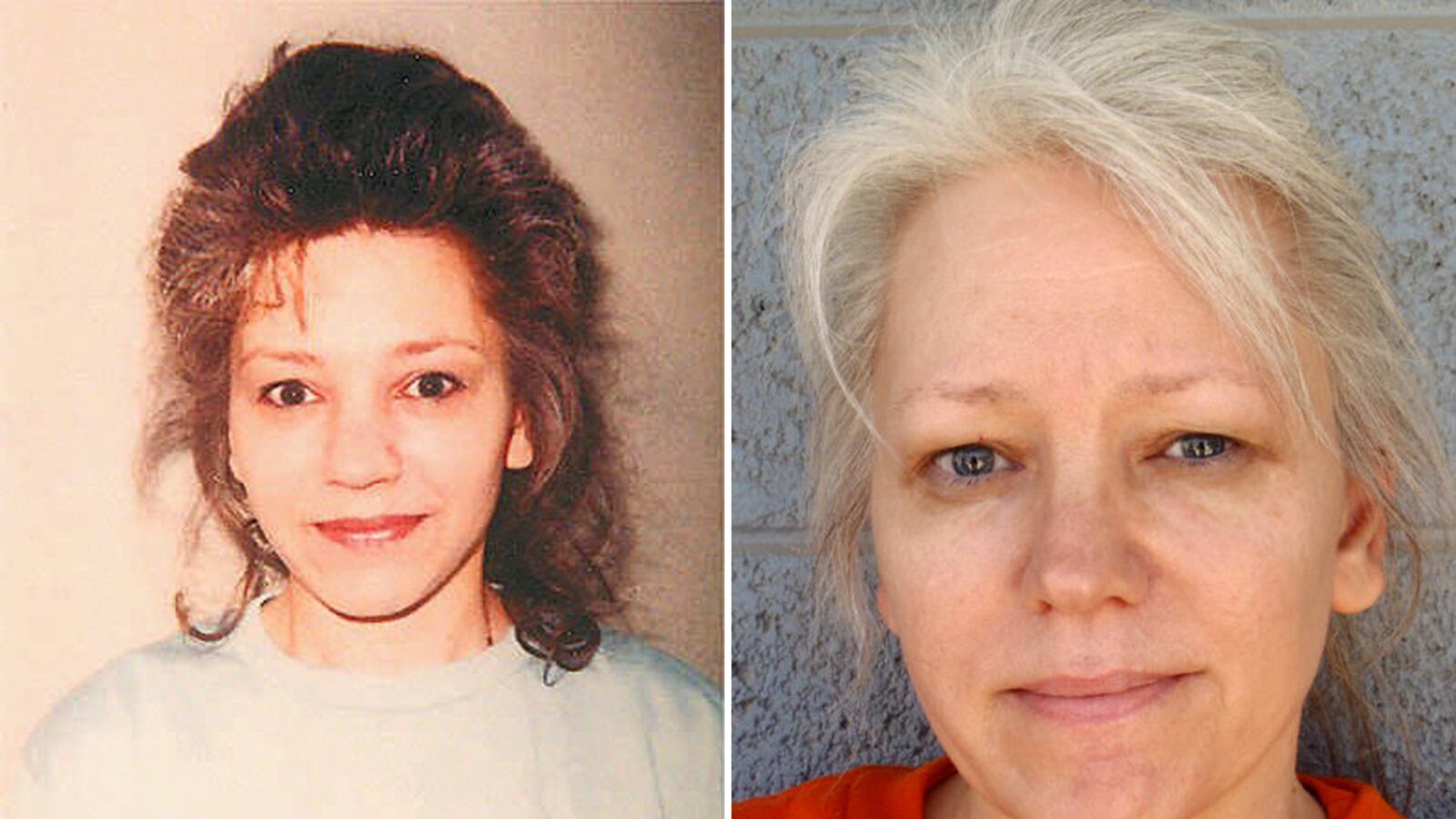

The three suspects were tried separately, convicted, andsentenced to die. At the time Milke entered death row, she was 26 years old, tall and slender with expressionless blueeyes and permed brown hair. In court proceedings and press interviews, sheprofessed her innocence, claiming Saldate had a history of lying under oath andhad fabricated her confession.

This March, in a ruling that went largely unnoticed in astate transfixed by the salacious Jodi Arias murder trial, the Ninth CircuitCourt of Appeals reversed Milke's conviction in what Chief Judge Alex Kozinskidubbed a "troubling case."He called into question what he said was Saldate's possible "misogynistic" attitudetowards vulnerable civilian women over whom he had power and noted Saldate had a documentedhistory of lying under oath.

In an unusual move, the appellate court also ordered Milke’s entire case file be turned over to the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division as well as the U.S. Attorney's Office in Arizona "for possible investigation into whether Det. Saldate's conduct, and that of his supervisors and other state and local officials, amounts to a pattern of violating the federally protected rights of Arizona residents."

The appellate court also ordered that Saldate's entirepersonnel record be turned over to the federal court, and barred Milke's"illegally obtained confession that probably never occurred" frombeing used in a second trial, should Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomerydecide to retry her. (Montgomery's spokesman, Jerry Cobb, declined to comment.)

Milke, now 49, was jailed the day after Christopher's death.She has been behind bars for 25 years and on death row for 22 years. From herprison cell, she refused to comment. Although Milke is still on death row,she'll likely be released in a matter of weeks if Montgomery declines to retryher, says Lori Voepel, Milke's lawyer.

Armando Saldate, who retired from the Phoenix Police in1990, the same year Milke was convicted, also declined to comment for thisstory.

But Kozinski's blistering 60-page opinion and other court records shed light on the alleged police corruption, prosecutorial overreach and judicial carelessness that fused into a miscarriage of justice that might have sentenced an innocent woman to death.

Court records indicate that neither Styers nor Scott would testify against Milke. Since there was no physical evidence linking Milke to Christopher's murder, prosecutors relied on the testimony of Saldate to convict Milke. The trial devolved into credibility contest between Milke and Saldate.

Milke testified she didn't know Christopher had died until Saldate informed her of his death in an interrogation room. She said she was "in shock" and "reeling" but the detective moved close to her and put his hands on her knees. She told the jury she hadn't understood her Miranda rights and had asked for a lawyer, but instead Saldate continued interrogating her and twisted her words into a fake confession.

"She was one of the worst witnesses I've ever seen," recalls Phoenix journalist Paul Rubin, who covered the trial. She broke her flat affect only to whine. Once, the prosecutor handed Christopher's shoes to Milke to identify and "she just nodded, " Rubin says.

Saldate, on the other hand, had been a police officer for 21 years, and had testified frequently in court. He convinced the jury that in 30 short minutes, Milke confessed. Although he destroyed his notes of the interview and failed to tape record it, Saldate testified that Milke confessed she worried that Christopher would grow up to be just like his father, a substance-abusing ex-con. That's why she "wanted God to take care of Christopher," Saldate testified.

The trial court judge, Cheryl Hendrix, refused to allow Milke to subpoena Saldate's personnel records, which included a reprimand and suspension for seeking sexual favors from a woman Saldate had pulled over during a traffic stop. The personnel records would have disclosed a "misogynistic attitude towards female civilians" that was "highly consistent with Milke's account of the interrogation," Judge Kozinski wrote. But the prosecution, Kozinski wrote, wrongfully "suppressed" the report that might have resulted in a hung jury that would have spared Milke a death sentence.

After Milke was convicted, her defense investigators spent 7,000 hours poring over court records. They discovered eight separate cases in which judges determined that Saldate either had lied under oath or violated the constitutional rights of people he interrogated. But Hendrix, the judge, still decided that Saldate was more credible than Milke.

Milke's legal team filed an appeal in federal district courtin Phoenix. In this case, a federal judge "said nothing at all aboutSaldate's numerous instances of lying under oath, which tainted prior criminalcases. I find this omission inexplicable and conclude he must have overlookedthem," Kozinski wrote. Further, the judge did not force the Phoenix PoliceDepartment to turn over Saldate's complete personnel file to Milke. She lost again.Her Ninth Circuit appellate case was filed in 2010.

In overturning Milke’s conviction, the appellate court didn’t find her innocent. "Milke may well be guilty, even if Saldate made up her confession out of whole cloth," Kozinski wrote. "After all, it's hard to understand what reason Styers and Scott would have had for killing a four-year-old boy. Then again, what reason would they have to protect her if they knew she was guilty?"

Rubin, the reporter, remains ambivalent about Milke's guilt. He remembers Milke was "kinda flirty" in jailhouse interviews and recalls chilling police photos of the blue gum clenched in the dead child's teeth.

Several years ago, Rubin says, he saw Milke during a court hearing. "She was a hunched-over white haired woman," he says. "I was shocked."