In terms of sheer cinematic craftsmanship, Roman Polanski has few living rivals. He always knows precisely where to place the camera, consistently elicits fine performances from actors, and, although most of his recent films have been trifles, is probably incapable of making a genuinely bad movie.

Like his previous film, Carnage, based on Yasmina Reza’s God of Carnage, Venus in Fur (which was the last competition film screened at Cannes) is a theatrical adaptation. Finagling with David Ives’s two-hander (an off-Broadway success that eventually transferred to Broadway)—the setting is changed from New York to Paris and the dialogue is now in French—results in decidedly minor Polanski. As in Carnage, he appears to be posing a technical conundrum—can a filmmaker transcend the limitations of theatrical claustrophobia and produce something other than mere canned theater?

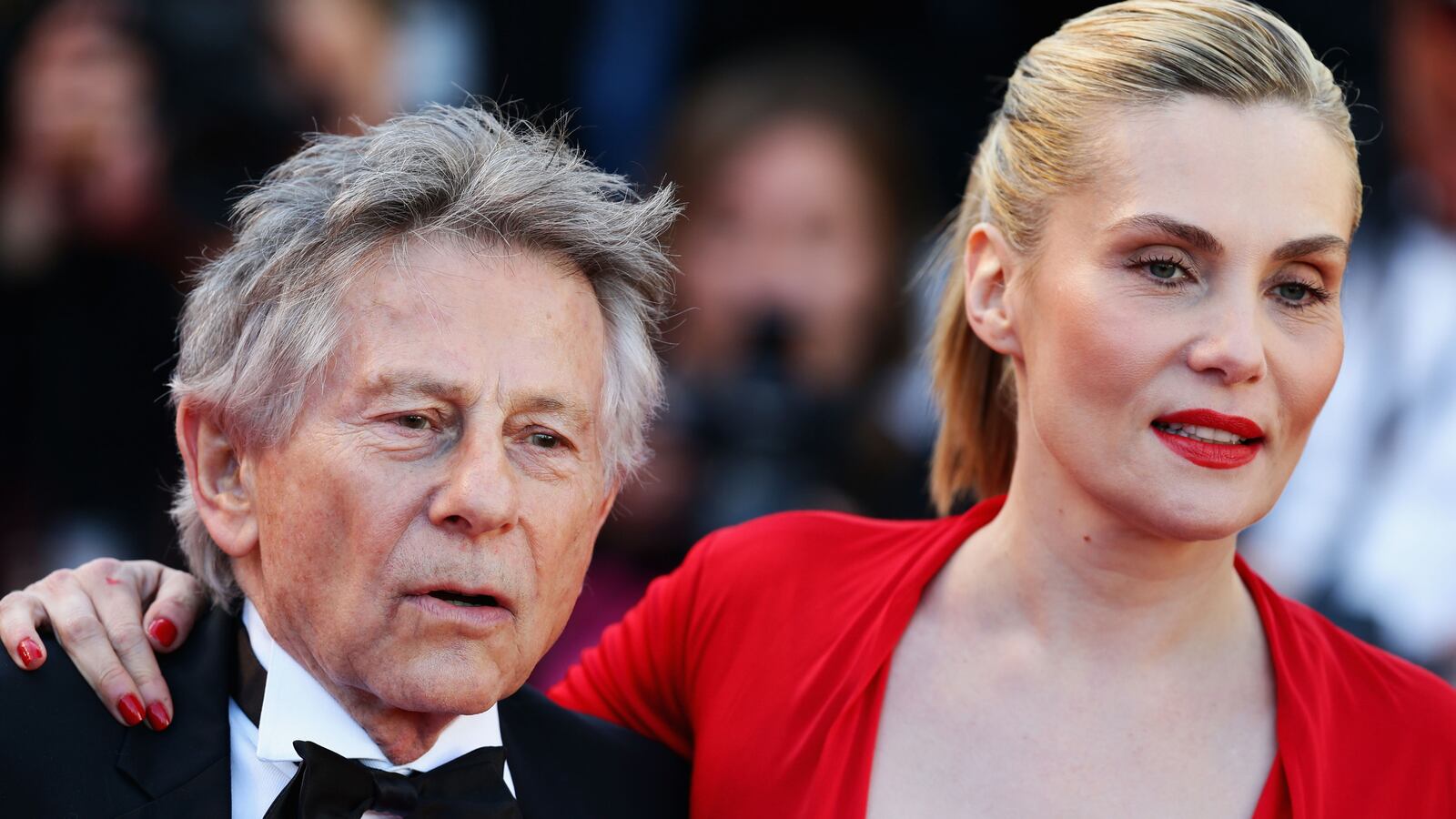

The fact that Polanski doesn’t totally succeed in this mission has much to do with the weakness of his source material. Ives’s play is a too-clever-by-half concoction that pits Thomas Novachek (Mathieu Amalric), the author and director of a play based on the 19th-century writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novel Venus in Furs, against Vanda (Emmanuelle Seigner), a bubble-headed actress who turns up late to audition for the lead role. Sacher-Masoch will always be linked to the term “masochism,” in both its psychoanalytic and everyday connotations, and much of the script, which Ives co-wrote with Polanski for the screen, hinges on a shifting power dynamic between director and actress. Vanda ends up being much less of a airhead than she initially appears. She’s able to turn the tables on the arrogant director and emerges, in character, as his play’s Wanda, a woman ready to play the role of sadist to Thomas’s newly forged identity as a submissive. Despite the sexy packaging, too much of this comedy-tinged drama triggers rather banal musings on the slippage between reality and theatrical artifice, as well the roles of master and slave assigned to directors and actors.

For film buffs, the real allure of Polanski’s film resides in its ability to recapitulate themes he’s mined during a long career preoccupied with highly fraught male-female psychodramas. As Seigner (who plays Vanda and, as Polanski’s wife, has obviously become intimately familiar with his work) observes in the press notes, “there was the period dress from Tess, the knife from Rosemary’s Baby, the make-up like in Cul-de-Sac, Thomas dressing like a woman, as in The Tenant ... There were so many wonderful little echoes.”

For many critics, gifted young actress Nina Arianda’s star turn as Vanda was the highlight of both New York productions. While Arianda's Vanda made a gradual transition from clueless novice actress to empowered siren, Seigner’s tone is shaky in the early scenes. Before long, however, she shines as the dominatrix of the later sequences. Almaric delivers a suitably nuanced performance as Thomas, the writer-director whose smugness is left in tatters by the film’s conclusion.

In 1967, long before the advent of the Twilight franchise, Polanski directed The Fearless Vampire Killers, a fondly remembered horror spoof. Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive, a competition film that screened for the press Friday, is a toothless attempt to fuse the vampire genre with art-house sangfroid.

Eve (Tilda Swinton), perhaps the most literary vampire in cinematic history, resides in stately anguish in Tangier, the laidback Moroccan city once home to William Burroughs and Paul Bowles that, unsurprisingly, appeals to the often irritatingly hipper-than-thou Jarmusch. While she enjoys shooting the breeze with Marlowe (purportedly a fanged version of Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe who’s played by a splendidly disheveled John Hurt), she misses Adam (Tom Hiddleston), her centuries-old lover, and soon flies out to Detroit to be reunited with this anemic musician. Her kid sister Ava (Mia Wasikowska) is also hanging out in Detroit and convinces the oldsters to go out for a night of clubbing.

Only Lovers, despite a thin conceit, offers some modest pleasures. Instead of feasting on human flesh, Jarmusch’s vampires search for blood, their drug of choice, in hospitals and other select venues. He also has considerable fun with a hipsterish trope that posits vampires as bohemian elitists. (Swinton has an especially good command of vampire hauteur.) They disdainfully label humans “zombies,” and Hiddleston has the best line of the film when he christens Los Angeles “Zombie Central.” Nevertheless, a little of this sort of banter goes a long way.

Directorial stars reign supreme in the Cannes competition. For more adventurous filmgoers, the true gems in the 2013 festival could be found in “Un Certain Regard,” a sidebar featuring more experimental movies by directors yet to become marquee names. To cite one standout, dissident Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof's Manuscripts Don't Burn is a powerful account of a trio of writers pursued by an assassination squad determined to obliterate all vestiges of dissent. (The film was shot clandestinely in Iran; in order to protect them from official scrutiny, the cast members’ names do not appear in the credits.) True cinematic marathoners with the requisite stamina deemed Filipino director Lav Diaz’s 4-hour-and-10-minute North, The End of History, a strangely hypnotic saga of a loquacious intellectual who turns out to be a brutal rapist and killer, the festival’s most rewarding entry. Although Venus in Fur and Only Lovers Left Alive will doubtless soon be coming to a theater near you (Only Lovers was just picked up by Sony Classics), it will take more industrious foraging to find a movie theater (or more likely a repertory cinema or archive) willing to screen Diaz’s brilliantly cryptic epic.