Days before my graduation some 25 years ago, I asked my Indian-American parents when they planned to arrive for the big event. To my great shock, my father said he and my mother weren’t going to attend. “When you get your Ph.D., I will come,” he said.

At the time, I was crushed. All of my friends’ parents would be there and, at 22, graduating from the University of Pennsylvania was my single biggest accomplishment. What I didn’t realize is that for my father, like many Indian-Americans of his generation, the bar was very high, and for their children it was just as high. Graduating from college was like getting to base camp in the Mount Everest–like climb in life.

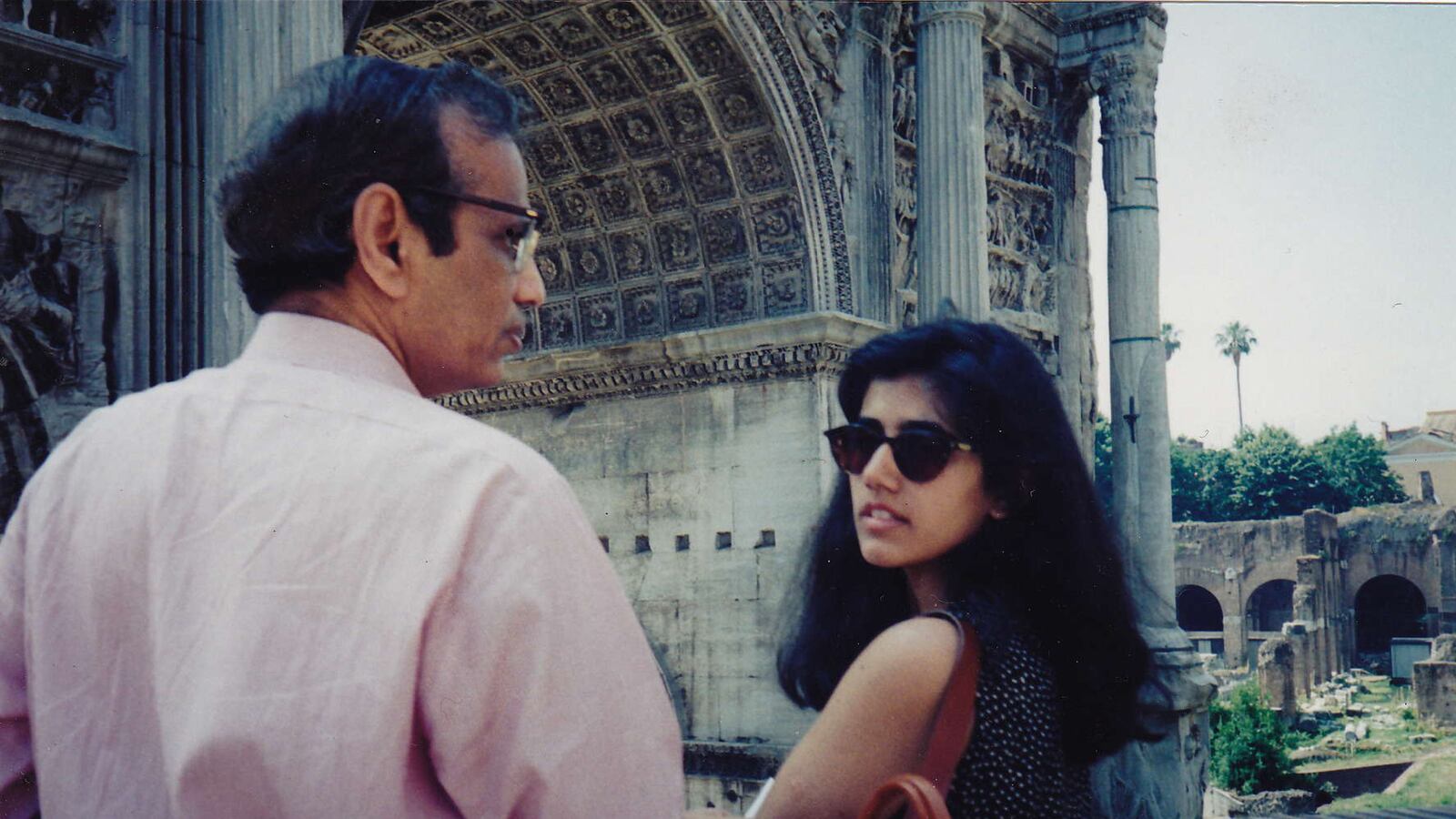

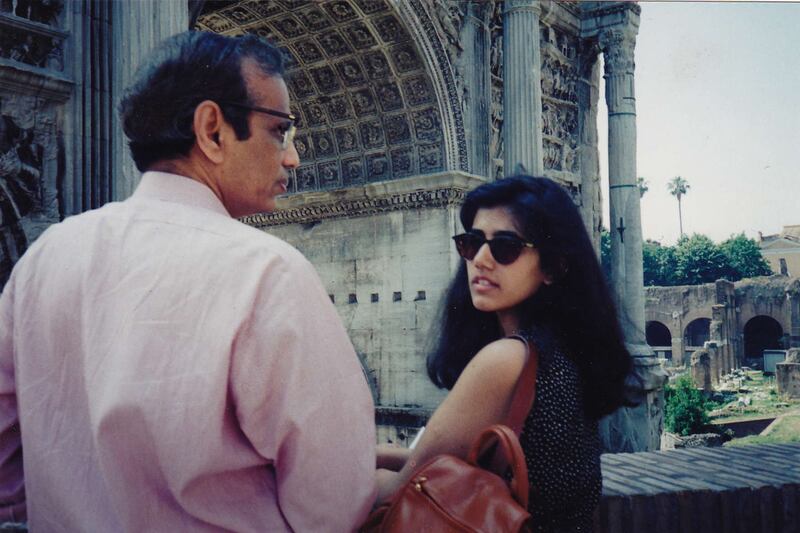

In 1958, over the opposition of his own father, who wanted him to stay in his prestigious job working for India’s primary scientific institute, my dad boarded a ship from Cochin Harbor in the Indian state of Kerala to embark on a monthlong journey to America. He had $100 in his pocket, and by the time he arrived in America he had spent most of it—$40 for a watch he bought in Yemen and $9 for an excursion to Pompei during a stopover in Naples.

He came at a time when hostile immigration laws allowed for only 100 Indians to be admitted into the country each year. Fear of disease, particularly tuberculosis, meant that my father had to tote X-rays of his lungs that were examined on a light box when he arrived in New York harbor.

For him, I later realized, the trip was a journey of great distance psychologically as well. He had grown up in a small fishing village. None of his siblings would ever leave India, but my father had a dream to study botany under one of the best-known names in the field. He wrote to the professor at Princeton University and was admitted to its graduate program in biology.

His ambition was typical of other, earlier waves of immigrants to the United States, but the speed with which he rose from fresh off the boat to an established professor is a uniquely Indian-American story that is repeated every day in fields as diverse as entertainment and law among Indians of all ages.

Less than 50 years since Asian immigration into the U.S. was relaxed, Indians have vaulted into America’s power elite. They now head Fortune 500 companies like PepsiCo (think Chennai-born Indra Nooyi) and mete out law and order (think principal deputy solicitor general, Sri Srinivasan, a nominee for a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, and a possible U.S. Supreme Court justice one day). They create movies and write books (think M. Night Shyamalan, the Pondicherry-born director of The Sixth Sense, and Jhumpa Lahiri, the Pulitzer Prize–winning Bengali fiction writer) and they start innovative companies (think Vinod Khosla, the cofounder of Sun Microsystems and a prominent venture capitalist).

Over the years, many of my American friends have asked me why Indian-Americans are so successful. Are Indian homes filled with Tiger Moms as Chinese homes are?

Not exactly. Indian-American parents are no sloths, but they are no tigers either. China is an authoritarian state and India is the world’s largest democracy, where an “anything goes culture” prevails. Those sharp political differences lead to contrasting parenting styles. Indians immigrated to America to escape India’s chaos—even today in Indian cities it is not uncommon for traffic to come to a standstill because of a wayward bull—but they have never completely shed their cultural baggage. Like Chinese parents, they have high expectations for their children, but they eschew the militant discipline promoted by Chinese-American mother Amy Chua. Instead, they till a middle ground, choosing to teach by example rather than by browbeating.

Born to high-achieving Indian parents—my mother came independently in 1959 to take up a job at Brooklyn Public Library—I stood in awe of my parents’ accomplishments. For me, there was no better motivator for success than the desire to live up to them. I may not have agreed with my father’s decision to miss my graduation but, knowing his journey, I wasn’t going to hold it against him either. Instead, I endeavored to strive even harder so that I would not debase his legacy.

I read a letter recently from Harvard medical student Deep J. Shah that reminded me of a salient quality in Indian parenting. “It was my parents’ way of living that impressed upon me the meaning of ‘duty,’” he wrote. “In tracing their paths, I learned being dutiful is a choice—an opportunity, not an obligation.”

Similarly, I learned that studying was a choice, not a chore. We lived in a home surrounded by books, and my parents were voracious readers, newsmagazines and biographies for my father and theology and philosophy for my mother. During his working life, my father visited the office every day, even on holidays. Whenever I would ask if he was going to work, he would reply: “No, I am going to study.” In our house, there was an unspoken nobility about studying, a virtue that as a young child I desperately wanted to emulate.

For Western parents, uncomfortable with the regimented recipe for child-rearing, the Indian way offers a path of compromise. Instead of punishing and ostracizing, Indian parents drive their children to excel by showing, more often, than telling. Shah soaked up the notion of duty by watching his parents take in a stream of relatives, even when it strained them at times. My cousin imbibed the virtues of hard work by seeing his mother get up at dawn and labor till night, eschewing dates and frivolities after her husband died. And I devoured books and immersed myself in my studies because in my house that was simply what we did.