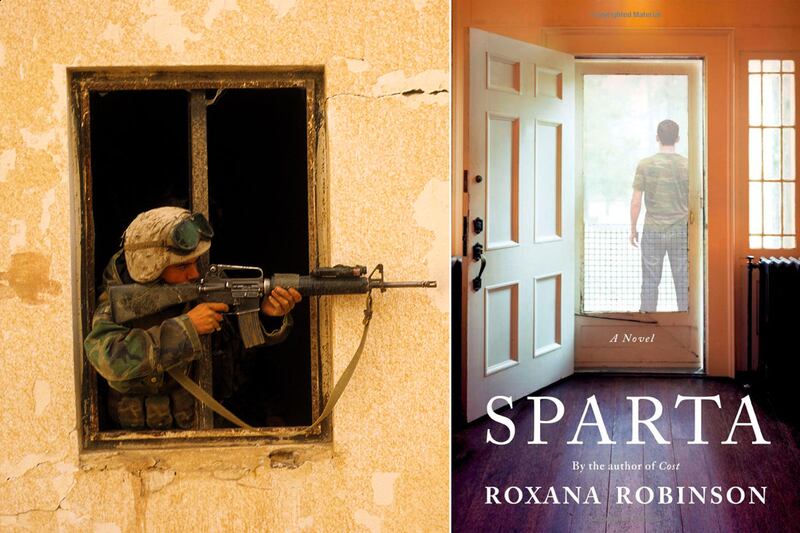

Roxana Robinson’s haunting new novel, Sparta, is a harrowing account of an Iraq War veteran’s homecoming. Robinson is author of four previous novels, a critically acclaimed biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, and three distinguished short-story collections. Over lunch in midtown New York, she told me that she read extensively while working on the book and spent four years interviewing Iraq War veterans. Getting to know the soldiers, she said, was a “like moving to a new country: I found myself in the middle of it, and then I wanted to learn the language and the culture and everything there was to know about the people.” Here’s more from our conversation.

Why did you choose to write your new novel from the perspective of Conrad, a 26-year-old Marine returning from tours of duty in Ramadi and Haditha?

Six or seven years ago I read an article about our troops in Iraq—how they were being sent out in unarmored vehicles, and being blown up by IEDs, and receiving traumatic brain injuries as a result. These were often undiagnosed, partly because the military was reluctant to remove troops from combat and partly because treatment was expensive. I just couldn’t get those three things out of my mind: the unarmored vehicles, the injuries, and the reluctance to treat. It was clear that we weren’t really protecting our troops. This made me wonder about the consequences of this war. So that article was the beginning. It was a new world for me—I’m a Quaker. I hardly even knew anyone who was in the military.

Conrad is a Marine officer who joined up in 2001, while he was a classics major in college. “The classical writers love war, that’s their main subject,” he tells his parents. “Being a soldier was the whole deal, the central experience. Sparta, the Peloponnesian War, the Iliad. Thucydides, Homer, Tacitus.” What was the meaning of ancient Sparta to you as you worked on this book?

My first encounter with the connection between the Marines and the ancient world was in a memoir called One Bullet Away, by Nathaniel Fick. Fick was a classics major at Dartmouth, and he became a Marine lieutenant in Iraq, and the combination fascinated me. As I learned more about Marine culture, I was intrigued to learn that Fick was not alone. References to the classics are rife among Marines, and their culture is full of intellectual threads: Marines are very conscious of their ancient forebears. They read the classics. One of Fick’s enlisted men was reading The Iliad during their trek across the desert toward Baghdad. The Spartans (who are the attackers in The Iliad) are commonly used by Marines as references to a heroic-warrior culture—they name their units the Spartans and their combat outposts Sparta. And the word “Sparta” is sometimes used as an adjective to mean “awesome.” Sparta itself is a very present and powerful idea among Marines.

Was Conrad's postwar trauma connected to the locations where he’d served?

I used Ramadi and Haditha because they were both dangerous and deadly, both of them centers of mujahedin resistance. Ramadi was the site of a sudden and ferocious citywide jihadi attack on Allied forces in the spring of 2004, and it saw some of the worst fighting of the war. Haditha is a small town in western Iraq, near the border of Syria. It was a stronghold of resistance, and in 2005 it was full of Islamic fundamentalists who had moved in to enforce brutal religious rule. Public whippings and executions were common, and the insurgents were extremely hostile to the Allied forces. During the summer a series of lethal IEDs killed Marines, and it was rumored that one Marine was taken alive and tortured. In the fall a huge IED killed a Marine and wounded several others. Immediately afterward was the shooting of 24 unarmed civilians, including women, children, and an old man in a wheelchair, by the Marines. This tragedy—all of it, the brutal suppression of the community, the lethal IEDs, and the massacre of the civilians by our troops—seemed to me to represent the deep black heart of this conflict. These Marines were based in a combat outpost they’d named Sparta.

How did the Marines you interviewed describe the homecoming process?

The reentry process was different for everyone, just as the war experience was different. But for many it was brutal—there was such a huge divide between the life they’d been living and the life back at home. One of the things that was so devastating was the fact that civilians didn’t even know there was a divide. The vets were helpless—helpless to articulate it, helpless to do anything about it, helpless to remake themselves into civilians. In some cases they couldn’t do it, couldn’t become civilians again, couldn’t envision living that sort of life again. In some cases they reenlisted, and in the worst of them, they took their own lives.

The biggest issue seemed to be the experiential gap between them. American civilians had no idea of how the vets had been living—that vets had based their daily lives on such different premises for the last four years. In America, most people don’t think daily about the questions of death and survival, honor and loyalty. But in Iraq, death was a constant presence. And it wasn’t just the fact of confronting death, it was also being in a continuing state of anxiety, and moral turmoil, and sometimes despair, and physical exhaustion, and utter boredom. In America, civilians didn’t know about any of this, or if they did, they didn’t know how to acknowledge it. Vets felt they had to protect themselves from conversations that devalued or trivialized what they’d been through: most civilians were either frightened, titillated, or indifferent to the subject. For the vets it became increasingly painful, and finally devastating, to realize how little civilians knew or understood about what had happened in Iraq.

When Conrad returns to civilian life in May 2006, he faces a barrage of symptoms—fear, insomnia, flashes of rage, flashbacks, headaches, nightmares, a sense of purposelessness. To what extent do you think his reactions are connected with this particular war?

I think coming home from any war means a huge letdown and a sense of purposelessness: it’s like being fired. You no longer have your job. You lose a sense of identity—though it’s much more than that. You thought you were fighting on behalf of the people at home, but after months or years of adrenaline and fear and exhaustion, you return to realize that no one knew or understood what you’d done. And what you’ve been has vanished. You are no longer that person. You must make yourself up new. And in some cases, what a soldier has gone through means he has been irrevocably changed, and the person he used to be can’t come home again.