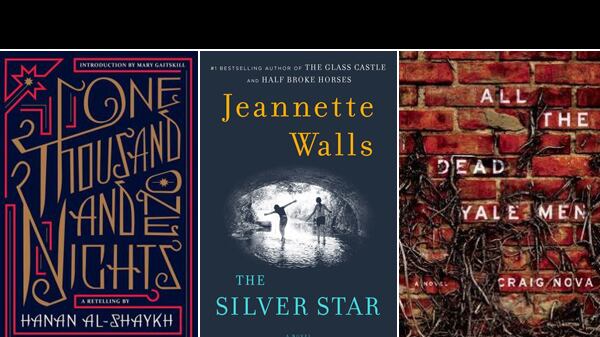

The Silver StarBy Jeannette Walls

Two girls strike out on their own across the country after their mother abandons them.

It takes only 20 pages of The Silver Star, the new novel from Jeannette Walls (author of the massively successful memoir of her impoverished upbringing, The Glass Castle), before the characters dive headfirst into their adventure. Twelve-year-old Bean and her older sister Liz find themselves abandoned in their California house one afternoon when their mother, a struggling singer who never found fame in the ’60s and suffers something like an artistic breakdown in 1970, skips town without warning. The two girls, not particularly alarmed by their erratic mother’s behavior, elude concerned police and get on a bus with their turtle, Fido, to Virginia, where they have vague memories of an uncle. Once there, as the girls learn about their family’s history, the world throws all sorts of problems at them, from the simple issues of adjusting to a new town and school to the more serious question of what happened to Liz in a car with the foreman of the town’s mill. Walls writes with the paired-down incisiveness of a memoirist looking for the significance of every incident, but it’s the way she draws Bean, so strong even in the face of all the additional challenges that come with her age, gender, and innocence, that will make this book a hit with readers. Fiction could do with a lot less 27-year-old men and a lot more 12-year-old girls.

—Nicholas Mancusi

All the Dead Yale Men By Craig Nova

The sequel to 1982’s The Good Son updates the story of the tough-as-nails Mackinnon family.

Craig Nova’s 1982 hit, The Good Son, dealt with the efforts a father, Pop Mackinnon, to steer the life of his son, Chip, in the direction of Pop’s choosing after Chip returns from flying fighter planes in World War II. All the Dead Yale Men, a sequel 30 years in the making, moves the narrative down one generation. Chip’s son, Frank, is in all kinds of trouble: there are material issues involving his career and finances, but he is more concerned about how to do right by his family, especially his only child, Pia, a fiery girl who has promised, or rather threatened, that she will be the last of the Mackinnon line. But Chip, the drunken old fighter pilot with shadowy ties to half of Boston, dies before he can offer much by way of paternal support to his son, and Frank is left with only memories and artifacts to guide him as he moves into darker and darker territory. Nova is a master of distressed psychological spaces: a chess match between Frank and “the Wizard,” a small-time punk who is courting Frank’s daughter—much to Frank’s extreme displeasure—is more thrilling than most car chases or shootouts. “Emotional explosions have their own revelations,” Nova writes, “which aren’t so obvious when you are flying through the air in the power of the first blast.” It would be wise to block out the time to read this in one sitting.

—N.M.

The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for GirlsBy Anton DiSclafani

A young girl deals with a dark incident in her past and her uncertain future at equestrian camp during the summer of 1930.

It makes sense that so many debut novels from young writers are coming-of-age stories; the beginning of the writers’ careers echoes the beginning of their characters’ adult consciousness, even if the specific events of the books don’t have much to do with the authors’ lives. So it goes in The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls from Anton DiSclafani, which takes place at an equestrian camp in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1930. The book starts with Thea Atwell, 15, arriving at the camp halfway though the summer session. She knows she is facing a type of exile from her family for something that she’s done, and between sections focusing on life at the camps, full of the jockeying, conflict, and claustrophobic drama that is the purview of fiction focused on groups of people in enclosed environments, we begin to learn her role in the tragic incident that changed two families forever. This novel is not what you might at first expect: what starts as something that resembles a bucolic tale of golden-age innocence quickly takes several dark turns, and DiSclafani weaves threads of violence, deviance, and sex through the affluent veneer of the camp. One imagines that this book will be gifted to more than one young equestrian on the basis of the title alone: perhaps a slight error for the giver, although the receiver will love it enough to tuck it under her thin camp mattress to keep it safe.

—N.M.

One Thousand and One Nights By Hanan al-Shaykh

A reinvigorated but wisely traditional retelling of the classic from the Arabian world.

The Arabian classic One Thousand and One Nights is filled with some of the written record’s most essential ur-storytelling. This version, by journalist, novelist, and playwright Hana al-Shaykh, catalogues the infidelities, murders, entrapments, and otherwise misbehaviors of opulent kings, poor fishermen, treacherous genies (“Jinnis”), and more. But what was most revolutionary about the book when it was first transcribed to paper from the oral tradition in 1450 is still most salient today. The virgin Shahrazad (or Scheherazade) relates these stories one by one in the bedchamber of a vengeful cuckolded king in order to stay her execution by his hand. But to say nothing of the innovative frame structure, what stands out here is the guile and agency of the female characters. Shahrazad “is not just out to save her skin,” Mary Gaitskill writes in the introduction. “She wants to heal; she is asking for forgiveness, not only for women’s sexual infidelity but for men’s violent possessiveness.” Evident in her facility to write in the timeless and magical vernacular of fairy tales, al-Shaykh clearly understood that the strength of these parables is that they require no modernization.

—N.M.

For a Song and a Hundred SongsBy Liao Yiwu

A Kafkaesque account of a Chinese poet’s four years inside a horrific prison.

In 1990 Liao Yiwu, a young Chinese poet, was jailed for four years after he wrote and distributed a poem called “Massacre” that condemned the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989. He began For a Song and a Hundred Songs in prison by scribbling on scraps of paper. But even after he was released, he had to write the book three times, since Chinese police raided his apartment and confiscated a handwritten manuscript in 1995, then absconded with his laptop computer in 2001. Finally a new version was smuggled to Taiwan and Germany, whereupon Liao was threatened with prison again if the publication went ahead. “Why can’t you write books about harmless romances, and we can get them published here and make you rich?” a police officer told him. Thankfully, Liao did not back down, telling his German publisher that he’d be willing to go to jail again to get the book released. What results is one of the most important documents of political imprisonment and torture about China ever written. The young Liao would have preferred to spend his days with thoughts of Walt Whitman, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Solzhenitsyn, and Chinese literary classics purling in his head, but was instead pushed by the Tiananmen Square massacre to take a heroic stance. He emerges from the horrors with a Kafkaesque account of life in the Chinese jails. Wardens and guards with names like Interrogator Wu and Officer Gong deprived the prisoners they hated of meat. When a prisoner named Epileptic deliriously snatched a slice of pork one day, fellow inmates jabbed a pair of chopsticks into his throat to try to retrieve the pork, but Epileptic swallows everything, meat and broken chopsticks and all. Liao didn’t take a hot bath for two years. He had to glue together thousands of medicine packets a day. He slept at the end of a big concrete bed perched over the toilet pit, and because he could easily fall in he’d obsessively scrub the area with toothpaste and a broken toothbrush. Inmates who were sentenced to death were called the living dead, with names like Dead Chang, Dead Lan, Dead Liu, and Dark Skin. There’s also Big Dick, Scholar Yang, Big Glasses, Gambler Zhang, Pervert Liu, Big Daddy, the Woodcutter, Old Xie, and Big Tongue. In the end, Liao himself was spirited out of China and settled in Germany. “Sometimes I wonder, am I still in jail or am I a free person?” Liao writes in the epilogue. “It really doesn’t make any difference in the end because China remains a prison of the mind: prosperity without liberty.” It is the hope that this remarkable book will make a difference somehow.

—Jimmy So