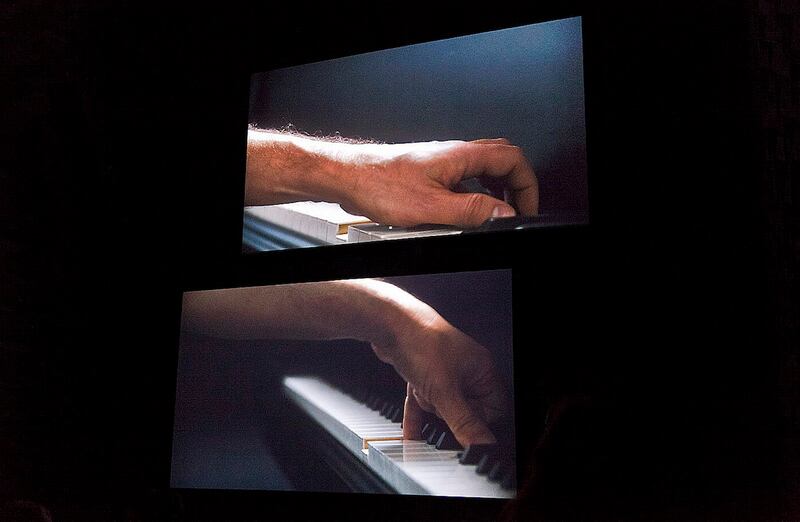

Anri Sala's "Ravel Ravel Unravel" project, representing France at this year's Biennale, is the best thing I've seen so far, and one of the best I've ever seen here. I'd need thousands of words to get at its complexities, but here are a few hundred to get us started.Sala's premise is relatively simple: He gets two great, heroic (male) musicians to record the concerto that Maurice Ravel wrote in 1930 for a pianist who'd lost his right hand in the Great War. In a grand central room of Sala's pavilion, two stacked screens show gorgeous, hi-def footage of each player's left hand as it strikes the keyboard. Although the pianists begin their solos at the same time, and the orchestra recorded with each is identical, their interpretations vary enough for the sights and sounds of their playing to pass in and out of sync. In one smaller side room – the first space you come to in the building – a smaller projection shows a close-up on a woman's face in extreme concentration; the soundtrack makes you think that she's playing the piano, except that her playing seems wildly distorted and fractured. In the building's final space, encountered after the main screening room, the camera pulls back and the woman's task is explained: She's standing at a pair of turntables, like a Hip Hop DJ, using her fingers to stop and start a pair of vinyl discs that bear the pianists' performances. Her goal is clearly to reconcile the two recordings so that their solos can be heard in sync, but the result is a series of hesitations and distortions in the sound as she "scratches" the twin records. The harder she works to make things right, the worse the result.So much for the premise. Read on for some of my reactions:– There's a sense of Sala "replacing" the missing hand of the original pianist, by doubling the players. Of course, his new, hybrid musician is a strange double lefty. A fractured body is healed, but its musicmaking is further damaged.– There's a fascinating tension between the visually powerful moments when we see the pianists' hands flying across their keyboards, and the visually placid moments when those hands are at rest – despite the aural frenzy of the orchestra playing its parts offscreen.– Surprisingly, the doubled recording of the Ravel is not cacophonous at all. At most, the piece underlines a common notion of Ravel as predicting later, more strenuously modern music. What you hear could be Ravel reworking his own thoughts on music, if he'd lived into the 1960s.– There's also a sense that counterpoint, which has been Western classical music's most notable feature, has been turned into the aesthetic principle behind Sala's contemporary visual art. It's hard to sort out the echoes and repeats in Ravel's original score and the echoes and repeats introduced by Sala.– The woman's attempt to sort out the musical jumble comes care of DJ culture, often seen as standing in opposition to the classical tradition and for a rejection of Bachian order. Yet her two hands, delicately working the turntables, come off as strangely close to the pianists' twinned left hands at their keyboards. (Could someone write a piece for a one-handed turntablist?)– The project is about recording and playback technologies – visual and aural – as much as about live performance. Sala uses different speaker arrays in each room as well as different sound baffling (the central room has foam panels that eliminate almost all echoes off its walls). The separate content in each room is matched, and complicated, by different means of reproduction.– There's a notable contrast between our sense of being in the presence of intuitive choices being made, as we watch each pianist do his particular thing, and our realization that the actual footage that we watch and hear is set down for good, without the possibility of alteration. In what sense, then, are we actual witnesses to improvisation?–There's also a lovely match between the way the pianists seem to improvise, but within the narrowest of limits (hence their being often in sync), and the improvisations of the cameramen as they follow the movement of the musicians' hands, pull their focus to different parts of the keyboard or drag our attention from flying fingers of the left hands to right hands not moving at all. And all along we're never sure how much freedom there really is for either musician or cameraman to stray from a script set by Sala – and Ravel. This, you could say, is the tension at the heart of much of the West's performative art.– There are gender implications. The piece underlines the "maleness" of the Romantic tradition in music – the concerto's one-handedness was "produced" by a war – and then positions its woman as stuck between gigantic male egos, hopelessly attempting to reconcile them.– A final marker of the success of this strange collaboration between Sala and the long-dead Ravel: Despite the extreme complexity of the piece, visitors stayed riveted for longer than they ever would in front of a painting or photo, or with a classical album. There's no plot, but visitors don't want to lose track of it.

For a full visual survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.