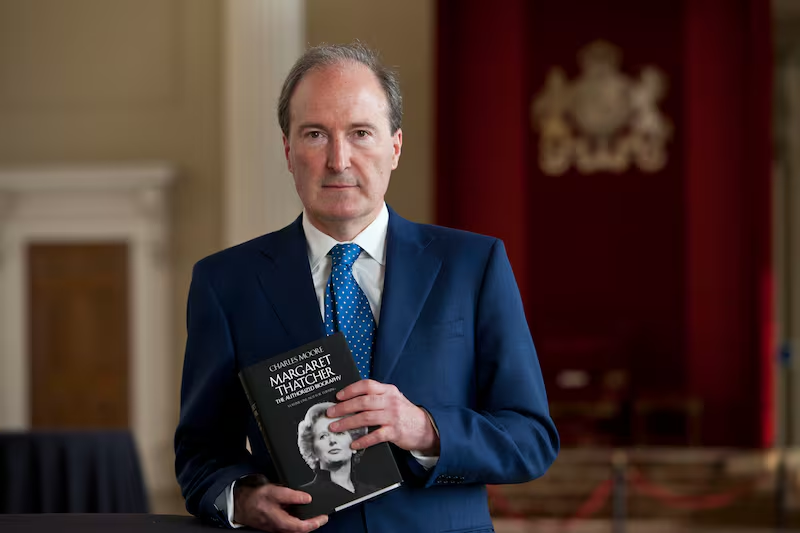

Margaret Thatcher died only eight weeks ago, but publishers are already racing to release books about the late conservative icon. Rush jobs and cash-ins are probably inevitable, but the first book across the finish line is volume one of Charles Moore’s authorized biography. Published only six weeks after her funeral, Moore’s 900-plus-page doorstop has already been hailed by A.N. Wilson as “the greatest political biography since Morley’s life of Gladstone.” I spoke with Moore, former editor of The Spectator, The Sunday Telegraph, and The Daily Telegraph, about his subject—her fierce regard for privacy, her playful sexuality, her relationship with Reagan, and her unlikely domesticity—his low opinion of most political biographies, and the time he spent editing a weekly political magazine when Thatcherism was at its zenith.

Mrs. Thatcher died April 8, and the first volume of your biography is already on store shelves in Britain and the United States. How were you able to bring the book to press on such short notice? Was it more or less finished at the time of her death?

Well, when Lady Thatcher asked me to write the book, one of her conditions was that it couldn’t appear during her lifetime. She was worried people would think she was trying to control it. By a sort of strange coincidence I finished correcting the last page of the last proof almost precisely the moment she died, though I didn’t know she was dying. So we were able to get it pretty well ready, with the plan that we would get it out as soon as was practical after the funeral.

What are the best biographies of prime ministers you have read? Did you look to any of these in particular while preparing Mrs. Thatcher’s life?

I think a lot of political biography is not very good, or at least not very interesting. Sometimes the detail swamps the personality. Or the personality isn’t interesting enough to sustain a certain number of pages. I feel particularly lucky with Margaret Thatcher because hers is. What other British prime minister since Churchill would you want to read a lot about? A huge advantage in this respect is the fact that she is the first and only woman to have been prime minister. Every male British politician, however talented, pursues the same sort of trajectory. With Mrs. T., whenever you’re getting bored with tax policy or whatever, there’s always some extraordinary event that comes along. The narrative keeps you going.

Readers of her two volumes of memoirs know that Mrs. Thatcher could be reticent about her personal life. How did you circumvent this in your interviews with her?

When she asked me to do this, she said that I could have access to her, her family, associates, people who had never spoken before, all her papers. Effectively, this meant that the key was turned in the lock and everybody wanted to help. Her sister, Muriel, talked to me and showed me letters Margaret had written to her. I might use Muriel as a main source and speak with other people who had known the young Margaret, and then I would go back to Lady Thatcher herself. If the question were about a former boyfriend, she would not be very happy to say anything, but she would confirm the truth. Like all great people, Lady Thatcher had a certain sort of egotism, but she didn’t like talking about herself in a “Me! Me! Me!” sort of way.

You were editor of The Spectator during much of Mrs. Thatcher’s premiership. How popular was she among traditional High Tories? Auberon Waugh seems not to have had much time for her, and wasn’t A.N. Wilson riding round on his bicycle declaring his support for Neil Kinnock?

Yes, Andrew did do that during the ’87 election, but then he loves switching around. Some High Tories who were not very interested in Liberal economics were very anti-Thatcher. There were some but not too many of these on The Spectator. Mostly such Tories were not big, paid-up Thatcherites, but they did enjoy that era very much. Perhaps I’m just projecting my own memories onto this, but there does seem to have been a sort of “Gosh, I’m glad I’m here” sort of feeling about.

Kingsley Amis once wrote that seeing Mrs. Thatcher in person was like “looking at a science-fiction illustration of the beautiful girl who has become President of the Solar Federation in the year 2220.” Was she aware of her sex appeal? To what extent do you think she made an effort to capitalize on it politically?

[Laughs] Well, I think that she was aware of it, but one of her great skills was that she would never have admitted this even to herself. This was one of her skills, never revealing her hand or even what game she was playing. She was such a proper person that the sexuality was sort of sublimated. She never exceeded boundaries—she wasn’t naughty. But she could be playful, and she certainly loved male attention and knew how to give it back. She had a tremendous ability to concentrate on a man to whom she was talking. She could be quite touchy at times, brushing dust off a man’s collar, telling him how brilliant he was. She was also very keen on clothes: handbags, shoes, being all made up, hair being beautifully done. She was almost never dressed informally. There are perhaps two pictures of her in trousers. She always said that she must look her best for Britain. This was very important with world leaders, who would be half frightened, half thrilled when meeting her.

Reactions to Mrs. Thatcher’s death in the American press tended to focus upon her relationship to Ronald Reagan. How close were they?

I think they were very close, though I say that with a couple of qualifications. They were very different people. Their characters were complementary, but certainly not the same. There is an example in the book where she comes out of a meeting and says, “There’s nothing there.” She was often shocked by things President Reagan didn’t know. But she knew how good his character was for his job, and she had an enormous amount of respect for him. It’s important to note that their friendship was formed not in office but in opposition. From 1975 onward, they really did feel that they shared a task. When Reagan rang her up to congratulate her in May of ’79, No. 10 Downing Street wouldn’t put him through because they thought he wasn’t important enough. They were both outsiders at this point.

What can you tell us about Mrs. Thatcher’s domestic habits? Was she much of a cook? Did she iron Dennis’s shirts?

She was very house-proud. Do you use that expression in America?

No, but—

You see what it means, anyway. She loved a tidy house full of bright, beautiful objects like Crown Derby china, with everything neat and shipshape. No. 10 in her time was quite a cozy setup. In the evenings she would take her shoes off, put her feet up, have a glass of whisky, and get on with her work. She saw food as fuel, but she liked cooking. When you’re prime minister, you don’t get money for food or for staff unless they’re for official entertaining. So when she was working late at night on speeches, she would take staff up to the flat and cook for them. She’d cook frozen meals from Marks & Spencer and boil up some peas. She loved all that. She always cooked Dennis’s breakfast when she was prime minister.

Finally, when can we expect volume two?

I don’t like that question [laughs]. I’ve done a good deal of it, but not nearly enough. Let’s hope within the next two years.

This interview has been edited and condensed.