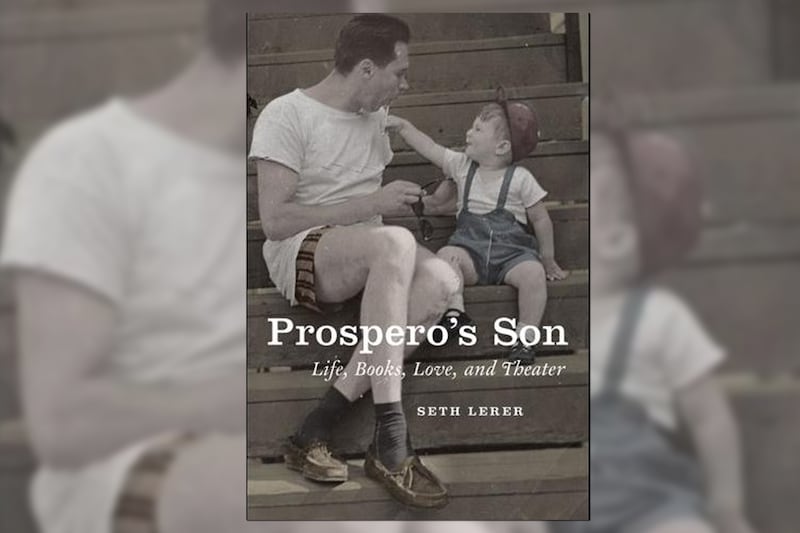

Some fathers take their sons to baseball games, play catch with them in the sweet evenings after work, or spend a Saturday beneath a car engine in the driveway. Some coach their boys to competitions, share a first drink or a first drive, or welcome them into manhood with a toast.

My father took me to the theater. Four years old, and I was on the subway, the old BMT from Brooklyn to Manhattan, just making the matinee of Bye, Bye, Birdie. We sat high up, in cheap seats, but with a full view of Conrad Birdie’s skintight, gold-lamé pants. Paul Lynde minced, Susan Watson swayed, and Dick Van Dyke, the man I always thought my father tried to look like, waved his accusing finger.

I had grown up with Dad’s theatrics. He and Mom had met in the late 1940s, in a Brooklyn College production of Blithe Spirit, and by the time I could remember things (10 years later), they were still rehearsing. Who recalls the “cast albums” of the 1950s? We had them all, lined up in lieu of books along the living-room walls: The Boyfriend, The Music Man, My Fair Lady. I’d hold the album covers in my hand, the arabesques of Al Hirschfeld’s covers capturing my eye, and sing along. When I was 6, I got a tape recorder for my birthday, and Dad turned it on to have me sing a song from The Music Man. I got the tune, but barely knew the lyrics, and to this day I remember them like this:

Goodnight my someone,Goodnight my love,Sweet dreams my someone,Sweet dreams my love,I wish I may, and I wish I might,So goodnight my someone, goodnight.

I sang into the microphone, not knowing what I may or might, or who my someone was. But then that night, Dad played it back to me in bed, like a lullaby, my own recorded voice singing myself to sleep.

Father’s Day never worked for us. It was too late in the year, long past the Broadway season but before we’d all pack up for summer camps in upstate New York—places with names like Kee-Wah, Locanda, Tagola, where Mom and Dad were acting coaches, set designers, and directors. There was nothing to do in June but wait it out, or pull the Playbills from the drawer and reenact the plays we’d seen: Camelot with Burton, The Sound of Music with Mary Martin.

I grew up. We left Brooklyn for suburban Boston, then Pittsburgh, as Dad pursued careers he thought would help him pass as straight: graduate school at Harvard, a consulting job in education, and then after Mom and Dad divorced, government work in D.C. But always, there was acting. He’d try out for parts with local amateur groups, his tall flamboyance shattering the clam of their incompetence. By the time he was in Washington, on his own in the 1980s, I’d get a phone call once a month: drive down, you have to see me, I’m at the Folger, the Kennedy Center, the Little Theatre of Alexandria. All were minor parts, a few no more than walk-ons. Only once did he take top billing, somewhere in suburban Maryland, and my brother joked: oh, yeah, Marat-Sade at the dinner theater in Fredericksburg.

When he retired to San Francisco, no roles came up. Well, he’d say, this really isn’t much of a theater town. But everyone was always on the stage. I’d walk around with him along the Castro or in North Point just to watch men dressed as nuns. He’d put on his hand-knit sweaters and his Gucci’s and his rings, and we’d go out to lunch. One afternoon, we sat down in a restaurant, and before the waiter could say anything, Dad put his arm on him and asked, in a voice that tried to be King Lear but sounded more like Oscar Wilde, “Can you believe, my son is taking me out to lunch?” To which the waiter replied, “If that’s your story.” One day when I was in the city, wandering to an appointment, I caught sight of him across the street, in a full-length fur coat, open like a cape, striding like David Belasco into Tully’s Coffee.

After he died, I went through all his things: the leather jackets and the implements, the matchbooks from the Endup and the Stud Bar, the letters from his lovers. I’d wondered if he’d really found his role, if he could finally play the part his all-too-straight sons had denied him. I rifled through his drawers until I found a box of photographs: 100 8-by-10-inch glossy head shots, all of them the same, his eyes right at the camera, his silver beard catching the flash, his mouth just slightly open. What was he planning on doing with these photos? Were they the cover pictures for audition résumés? Gifts for friends? Or were they only paper mirrors, reflections he’d look at when he wished to see the person that he wished to be?

This Father’s Day, he’s been gone 10 years, and I remember what he taught me: that all life is a performance, and the parts we play can best be scripted by ourselves. The ’50s dad was not his role: no Fred MacMurray, no Carl Betz. He was more Harold Hill, The Music Man’s sharp salesman, letting us know that if we could only get the band together, only play in tune, it would be wonderful. He wanted rows and rows of virtuosos. But all he got was me on tape.

Maybe, though, what he really wanted in that tape was someone singing just for him.

Only in theater can the dead come back: Shakespeare’s ghosts, Coward’s blithe spirits. And so, tonight, I’ll sing for him, my absent audience. I wish I may and I wish I might.