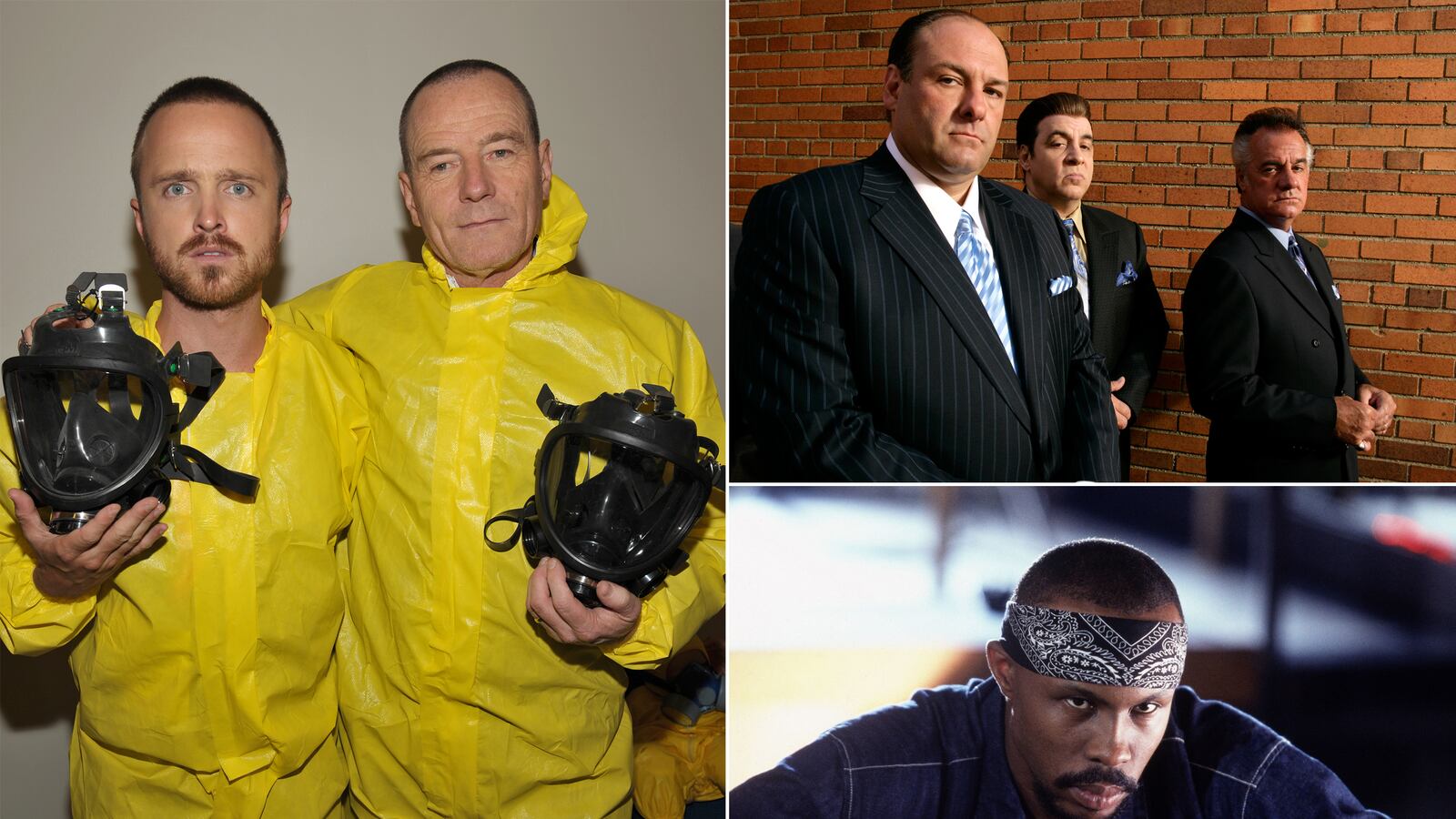

(1) The Sopranos: “College” (Season 1, Episode 5)

If there is a single moment that kicked off the golden age of cable-TV drama, this is it. Four episodes in to The Sopranos’ first season, we had already seen Tony Soprano act less than heroically, but little could prepare us for the sight of him killing a man with his bare hands, while on a tour of Maine colleges with his daughter, Meadow, no less. The idea came from a TV impulse as old as The Brady Bunch decamping for Hawaii. “After sitting there for three episodes [not including the pilot], I said, ‘Oh, I’m so fucking bored with this,’” said creator David Chase. “We gotta get these people out of town.” HBO head Chris Albrecht worried vocally that audiences would reject a “hero” who was also a murderer, but eventually relented (mostly, the victim, a mob rat, was made into a drug dealer to make his death slightly more palatable). Television would never be the same.

(2) The Sopranos: “Pine Barrens” (Season 3, Episode 11)

“I’ve always said, quite honestly, that I was never sure if The Sopranos was a drama or a comedy,” David Chase said. At it’s best, the answer was both, and that was never more true than in “Pine Barrens,” which is filled equally with slapstick and menace. In the episode, directed by Steve Buscemi, the vaudeville duo of Christopher and Paulie end up lost in the snowy wilds of southern New Jersey (actually filmed in New York’s Harriman State Park) after bungling an encounter with a Chechen mobster. Meanwhile, Tony survives a steak to the back of the head from his latest volatile girlfriend, and Bobby Bacala models the latest in goombah hunting gear. If one hour showcases the full range of The Sopranos at it’s best, this is it.

(3) Six Feet Under: “The Foot” (Season 1, Episode 3)

Season 1 of Six Feet Under is a nearly perfect example of the kind of storytelling that 13 episodes allowed—deeper and more expansive than a film’s two hours, but more contained and serialize-able than a traditional network’s 22 or more. “The Foot” is where the intertwining stories of the Fisher family began to get cooking in earnest. Meanwhile, the eponymous appendage (stolen by Claire from a cadaver at the Fisher funeral home and delivered to an ex-boyfriend’s locker) made it as clear as “College” did for The Sopranos that SFU wouldn’t be a garden-variety family drama.

(4) The Wire: “Middle Ground” (Season 3, Episode 11)

For all the ways in which The Wire was an extended, passionate piece of social and political activism, its equal achievement was as deeply human drama. Of all the relationships on the series’s sprawling canvas, few were as complicated and compelling as that of drug kingpin Avon Barksdale and his cerebral deputy Stringer Bell. “Middle Ground” was the end of the road for these complementary men. Writer George Pelecanos called the scene of their final conversation, before each leaves to betray the other, “the best thing I’ll ever have my name on.” Meanwhile, Idris Elba, who played Stringer, strenuously objected to the manner in which his character was dispatched at episode’s end, but later caught up with Pelecanos in the parking lot, to shake his hand. “It’s only business,” Elba said.

(5) The Wire: “Boys of Summer” (Season 4, Episode 1)

The Wire’s ultimate ambition, David Simon said, was to “build a city.” That meant moving on from Season 1’s tight focus on the Barksdale drug organization and the detail of cops pursuing them to document Baltimore’s other institutions, each season acting like a new section of a brass rubbing being filled in, until the picture was complete. The show had already shown its willingness to disorient the audience by introducing a whole new set of characters—the white, working-class union men of the city’s dying port—at the start of Season 2. Season 4, which Simon had to summon his most passionate powers of persuasion to even get made, did one better. Based on Ed Burns’s experiences as an ex-cop teaching in the Baltimore public school system, it introduced us to four middle school children whose divergent fates would become the most emotionally compelling, devastating, and triumphant part of the series’s five-season run.

(6) Deadwood: “Here Was a Man” (Season 1, Episode 4)

If viewers knew anything about the real-world frontier town of Deadwood, South Dakota, it was probably that Wild Bill Hickok was killed there, during a poker game, in 1876. If they knew anything about HBO original series, by 2004, it was that any character could be dispatched at any time. Nevertheless, it was a shock for Deadwood, the show, to abruptly kill off one of its putative lead characters, and the only one played by a recognizable star (Keith Carradine), after a mere four episodes. In the process, the show’s themes of life and death, crime and punishment, and the forging of civilization out of Deadwood’s muck were all on poignant display.

(7) The Shield: “The Cure” (Season 4, Episode 1)

The Shield’s fourth season was the show’s most self-contained and its most satisfying. At its heart was the formidable character of Capt. Monica Rawling, played by Glenn Close, who provided a fascinating adversary and partner for Vic Mackey and a chance to deepen the show’s moral exploration of means versus ends into an explicit allegory of the Iraq War. Rawling’s appearance would also have a lasting impact on the golden age in other ways: it introduced Close to the satisfactions of working on TV—especially for actresses of an age at which Hollywood film offered fewer and fewer opportunities. Soon she would return to FX as Damages’ Patty Hewes, one of the few female characters as complicated and “difficult” as the era’s male antiheroes.

(8) Mad Men: “Marriage of Figaro” (Season 1, Episode 3)

Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner had been a writer on The Sopranos and an unabashed student of both David Chase’s style of show running and philosophy of storytelling. So it’s been no surprise that Don Draper has played the same seductive game with the audience as Tony Soprano: every time we find ourselves rooting for him, the show pointedly challenges us to think about what exactly we’re rooting for. By the time of this third episode of Season 1, we were well aware of Don as a liar, cad, and adulterer. When he gets drunk and misses his daughter’s birthday party (showing up later with a dog by way of apology), we realize for the first time that he’s also a terrible father. In other words, this was Mad Men’s “College” episode.

(9) Mad Men: “The Suitcase” (Season 4, Episode 7)

On some level, Mad Men, which takes place in a contentious office workplace, has always been as much about the process of creative, combative collaboration (the kind, say, that goes into creating a television series) as anything else. By mid–Season 4, Matthew Weiner’s insistence on putting his name as co-writer on nearly every episode had become so well known that it was the subject of a gag on 30 Rock. Weiner took the question on directly in a fight between Peggy and Don in which Peggy accuses her boss of stealing her ideas and never saying thank you. “That’s what the paycheck’s for!” Don yells. Inside baseball aside, “The Suitcase” marked the emotional height of Don and Peggy’s mentor-mentee relationship—and a final, moving goodbye to Don’s true identity as Dick Whitman.

(10) Breaking Bad: “Grilled” (Season 2, Episode 2)

One of the joys of writing Breaking Bad, Vince Gilligan said, was when he and his fellow writers would paint themselves—and, by extension, Walter White—into a narrative corner and then have to figure out an escape route. This has made for some of the most excruciatingly tense hours of television ever, as White has wended his inexorable way from nebbish, terminally ill chemistry teacher to meth kingpin. And no such episode was more harrowingly fraught than that of Walt, and his partner Jesse, trapped in the desert outpost of a psychotic dealer named Tuco and reckoning with Tuco’s paralyzed uncle who communicates entirely by striking a hotel-desk bell. This is TV that Hitchcock should have lived to see.