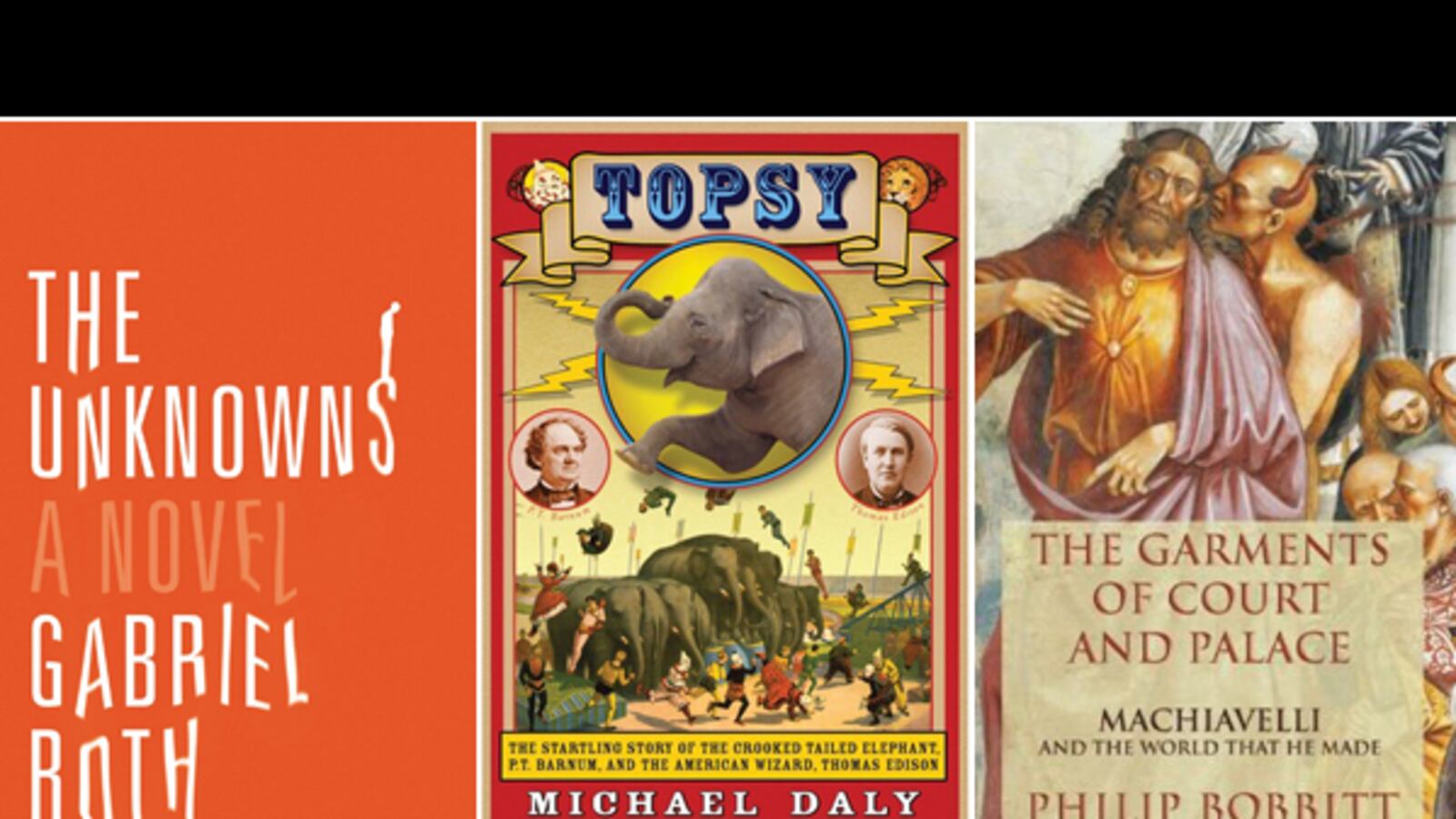

The Unknowns: A NovelBy Gabriel Roth

A debut novel about unlocking the code of the millennial heart.

By age 25, Eric Muller, the narrator of The Unknowns, the debut novel from former San Francisco Bay Guardian reporter Gabriel Roth, has already achieved today’s dorm-room dream: he has sold his Internet startup to a larger company for a sum that makes him a very wealthy young man. But his analytic mind, so useful in the world of computers, hinders his human interactions in the real world, especially with the fairer sex. It’s not that he can’t grasp the 1s and 0s; he’s a master of the system of banter, casually displayed confidence, and light drugs that it takes to get women to sleep with him. It’s the code to feeling some kind of deeper connection, this thing called love, that is harder to crack. He perceives dating with an omniscience reminiscent of Neo from The Matrix, as in this narration of his drinks date with the woman he thinks he might be feeling real feelings for: “I greet her without attempting any physical contact, because the available physical contact greetings at this point are a handshake, an air-kiss, and an upper-body hug, and none of those is a good way to start a date. Instead I pull out a barstool for her, a display of chivalry that I pretend to pretend is ironic.” As both characters explore the damages of their pasts, the book crackles with commentary, one part post-structuralism and one part observational comedy, on how we interact in 2013.

The Impossible Lives of Greta WellsBy Andrew Sean Greer

A magical, time-jumping story about the effects of circumstance on our souls.

How much of who I am has come from within, and how much has come from without? Would I still experience things the same if circumstances were different? In another age? In another life? These are the motivating questions of The Impossible Lives of Greta Wells, new novel from Andrew Sean Greer, bestselling author of The Confessions of Max Tivoli. In 1985’s AIDs-ravaged New York City, Greta Wells undergoes electroconvulsive therapy as a last-ditch effort to lift her from the depression she is left in after the death of her twin brother and a breakup with her lover. She knows there will be side effects, but she never expected to have lucid visions of a version of herself in 1918 and then later in 1941. In each era, the deck is shuffled: the brother is alive; the lover is recast as a husband off at war; her surname changes; a child appears. But in each world, similar problems and themes arise with Nietzschean eternal recurrence, and as the three tripartite Gretas converge, they must decide if there is really any difference at all. It should be no insult that this novel will appeal to young readers; the magical conceit here is well earned and imagined rather than gimmicky, and Greer writes with an acute sensitivity for the wonderment that underpins the human experience.

Five Star BillionaireBy Tash Aw

A collection of characters all trying to ride the tide of wealth in new China.

There was a time when the fiction of wealth (and the yearning for it) was distinctly American; think Horatio Alger up through The Great Gatsby and Bonfire of the Vanities. But as economic scales begin to tip east, it should come as no surprise that fiction about newly booming countries echoes familiar growing pains. Five Star Billionaire by Tash Aw, author of The Harmony Silk Factory, uses a kaleidoscopic approach to capture the struggles of all levels of China’s class system at once: there is a factory worker who hopes to become a waitress, a pop star, an heir to a real estate empire, and a hippie turned businesswoman, all drawn to Shanghai. The city has become a beacon of opportunity in the new China that exerts an Ellis Island–like pull on those in the region looking to improve their station in life (many of the characters are actually Malaysian) and is depicted colorfully as a character in itself. All these characters are united by the mysterious influence of a “five-star billionaire” who serves as a stand-in for the allure of wealth. There is more than mere allegory here, though. Aw has woven an impressive and contemporary human tapestry of a country that Western audiences would do well to better understand.

Topsy By Michael Daly

A tragic tale of a circus elephant who fell victim to human competition and avarice.

Topsy, by veteran journalist and Daily Beast writer Michael Daly, is the story of two forgotten American civil wars: the War of the Elephants, fought between circus men P.T. Barnum and Adam Forepaugh over whose elephants people should pay to see, and the War of the Currents, fought between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse over which type of electrical current (AC or DC) people should pay to use. At the precise intersection of these two conflicts of commerce was Topsy, an African elephant whose entire life was dictated and dominated by human cruelty, beginning with her removal from Africa to work in the circus and ending on Coney Island when Edison horrifically used her to demonstrate the dangers of his rival’s alternating current. Daly’s research is fleshed out in compelling prose that effectively draws out the macabre absurdity of a time when nothing seemed strange about an elephant being “sentenced to death.” One way to trace mankind’s moral evolution is through our treatment of animals, and it’s slightly reassuring to see that what once may have served as an afternoon’s entertainment is so morally bracing to read about today. Until one remembers that circus elephants still exist.

The Garments of Court and PalaceBy Philip Bobbitt

An astute reexamination of one of history’s most widely read documents of political instruction.

Machiavelli’s The Prince is as widely known as it is misunderstood. Today the name Machiavelli is synonymous with ruthless politics entirely detached from ethics, but in The Garments of Court and Palace, Prof. Phillip Bobbit shows that rather than a license for rulers to do as they pleased, The Prince is actually a guide for governance as the world moved from feudalism into an era of constitutionality. This is a rigorously academic book (which should not be taken as a slight) and one with a very specific project: to show that widely held beliefs about The Prince are actually incorrect, or at least more nuanced than generally conceived. The reasons for these misunderstandings range from historical scholarly oversights to simple mistranslations. Despite its rigor, the book is anything but a bore, and Bobbitt employs apposite historical asides from Italy and elsewhere to make his points, including some popes behaving badly whom fans of Showtime’s The Borgias will recognize. This book should be required reading for any young ruler trying to organize his principality without blunder, or, failing that, anyone interested in the history of statecraft.