Vladimir Putin’s Russia is a very new, and much wilier, type of dictatorship than 20th-century models. Living in Moscow you can almost kid yourself you live in the freest, hippest, edgiest city on earth. It’s not just the shops, galleries, iPads, and satirical glossy magazines; there are also TV channels (one), radio stations (at least two) and newspapers (several) where you’re free to rant and rage your opinion against the Kremlin all you like. You can even have the odd demonstration. You can, and the Kremlin wants you, to daydream inside the matrix of a sham democracy.

What you can’t do is start naming and researching and publishing the real corruption schemes that have made the small circle around Putin among the richest people on earth, or to challenge their power in any real way. Those are the rules, reinforced by an arch-cynicism informed by the disappointments of democratic reforms in the 1990s, a knowing postmodernism that claims that there are no ideals to fight for anyway. Sure, the attitude among the chattering classes has gone in the 21st century, democracy is a bit of a sham in Russia, and the whole system is corrupt, but it’s the same everywhere, so why bother struggling and aren’t we all, after all, getting so much richer?

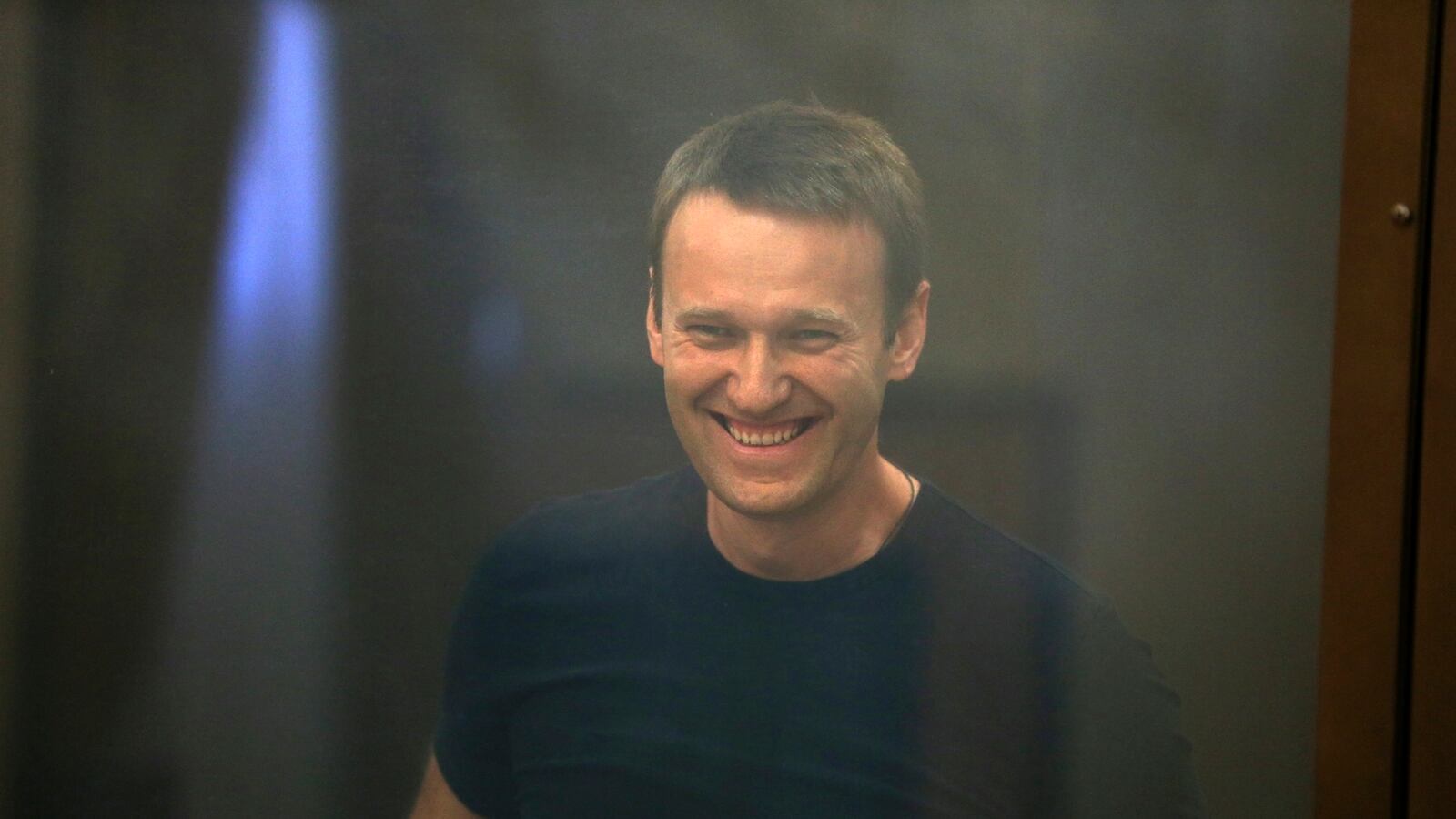

Then came Alexei Navalny. I remember when, sitting in a Moscow kitchen in the late noughties, I first saw his online video reports detailing corruption among the Putin elite. They’re going to kill him, was everyone’s first thought. You’re not allowed to do that. The Kremlin let him live because his bravery was useful: power players would leak Navalny information to undermine their rivals. But Navalny went further. He began to challenge not just individual companies but the very system itself. In a few sweeping months of protest in 2011 and 2012, he rose from anti-corruption blogger to politician, becoming the closest thing Russia has to an opposition leader.

Together with the corruption research, Navalny has brought a different way of behaving, of talking, and thinking. He avoids all the big words about “democracy” and “human rights”: these have long been co-opted, manipulated and bankrupted by the Kremlin. His speeches are full of a combination of street-fighting aggression and playground outrage: he legendarily called the ruling party United Russia the “party of nasties and thieves.” His clarion call, “One for all and all for one,” is from every Russian’s favorite childhood film, The Three Musketeers. It’s as if he’s trying to dig underneath Russians’ world-weary cynicism to find the wellsprings of a more moral outlook.

There is something of the folklore hero about him, a directness and (seeming) lack of self-conscious guile, the reckless protagonist going forward with his wooden sword of anti-corruption to wage war against what Navalny describes as the “giant spider sitting in the Kremlin … the hundred families sucking the blood out of Russia.” The ultimate aim of the whole Navalny project is to wake Russia up from its slumber of cynicism, what he calls the “battle of goodness against neutrality.”

For a brief moment during the 2011–12 protests it seemed as if Navalny had woken Moscow up. But then over the past year, apathy returned. Partly because of fear following a new round of arrests. But also because the honesty that Navalny is advocating—“We just have to stop lying and stealing,” he said in an interview—means facing up to not just the corruption at the top of the system but the everyday corruption that has become the norm in Russia, whether it’s buying your university degree or your driver’s license. It means leaving the comfortable matrix of Moscow life, which if you stick to small oases, looks and feels so much like London and New York, to face up to the monumental challenge of changing Russia.

Over the past year the chattering classes started to snap at Navalny. “He’s just an oligarchical project” said some; “He’s just in it for himself’ said others; “He’s a vile nationalist,” said even more. (He does have a disturbing nationalist streak, but that doesn’t change his arguments about corruption or apathy.) Moscow returned to its cynicism. At the same time the government kept the public entertained with the promise of fair elections for Moscow mayor, for which Navalny was even allowed to register.

When the news of Navalny’s five-year sentence came through, it should rationally have come as no surprise: he has violated every unwritten rule out there. But instead it came as a shock. Everyone I spoke to, and myself too, reacted physically: hands shaking, the desire to vomit, tears, cascades of swear words. Yes, everyone understood this was inevitable. But emotionally most of us had been in denial. It’s the reaction of those being forced to face up to something they’re aware of but don’t want to. The thousands who came out yesterday on the streets of Moscow, the first protests for a year, did so out of a sense of spontaneous emotional urgency.

For the moment the Kremlin has released Navalny pending his appeal. There are a thousand more ways to destroy him. Their main aim is for everyone to go back to sleep.