Secretary of State John Kerry is shuttling publicly (and talking secretly) in the Middle East. He hopes an Israeli-Palestinian peace process built on his kinetic presence can succeed where the high-profile initiatives of the past have failed.

Probably it won’t.

And if direct talks scheduled for Washington in coming days collapse, it’s quite possible a defining tweet at the end of this administration will read, “Obama's Mideast equations: Osama=dead, Syria=dying, Egypt=coup+chaos, Libya=Benghazi, Yemen=drones, Palestine=Hamas, Israel=Apartheid.”

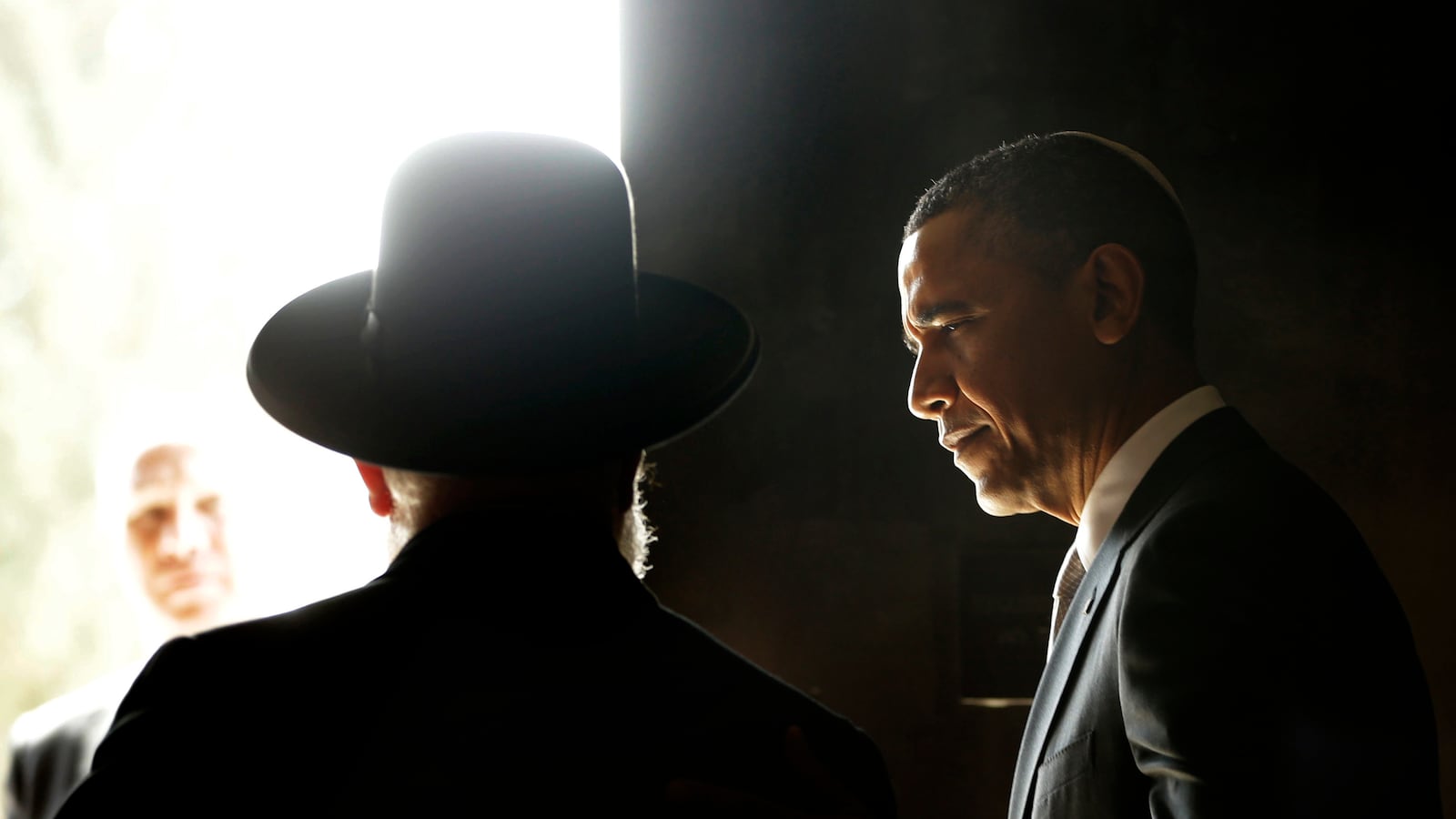

It’s not that President Barack Obama didn’t have a coherent vision of what he wanted to achieve in the Middle East when he came to office. The guiding principle of his policy was and remains very simple: an end to occupation—the American occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, and, yes, Israel’s occupation of the West Bank.

If he didn’t articulate an overreaching Obama Doctrine, spelling out unequivocal principles, that’s because he’s a realist, more or less in the classic vein of Hans J. Morgenthau, whose textbook you may remember from Political Science 101. Realistic policy is deeply suspicious of any doctrine; inevitably it smacks of what Morgenthau called “the crusading spirit” (think of the Global War on Terror) and it is “never true, because it is absolute, and the affairs of men are all conditioned and relative.”

Looked at from that perspective, Obama’s policy is quite coherent, and after years spent trying to extricate Americans from the disastrous occupations begun by the Bush administration, it was perfectly understandable. The public in the United States won’t support more military adventures with boots on the ground in the Middle East.

Just in case there are some romantics out there who think an intervention in Syria could be done on the cheap, for instance, Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, weighed in this week with cost estimates for even the most limited U.S. American military operations against the regime of President Bashar Assad.

Dempsey figured the price at a minimum of $1 billion a month, plus the risk of more civilian deaths, a power shift that could benefit extremists, and the major risk that American soldiers will get sucked into the fighting. “The decision to use force is not one that any of us takes lightly,” wrote Dempsey in a letter to Carl Levin, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. “Once we take action,” said Dempsey, “we should be prepared for what comes next. Deeper involvement is hard to avoid.”

The wiser course, Dempsey suggested, is “to isolate the conflict to prevent regional destabilization,” which brings us back, in fact, to the peace process.

We’ve all heard for years, to the point where it’s almost like background noise, that solving the Palestinian issue is the key to resolving many or most of the problems in the region. That’s probably not true anymore. Things have gotten so much more complicated over the last decade. But not solving the problem continues to make things worse in today’s desperately dangerous environment.

As Gen. James Mattis, the recently retired head of the U.S. Central Command, bluntly told the Aspen Institute this week, “We’ve got to work on [peace talks] with a sense of urgency. I paid a military security price every day as commander of CENTCOM because the Americans were seen as biased in support of Israel, and moderate Arabs couldn’t be with us because they couldn’t publicly support those who don’t show respect for Arab Palestinians.”

Even if the rhetoric of urgency is old hat, the context for it is not. Israeli and Arab leaders have said publicly, and reiterate privately, that if there is no two-state solution in the Holy Land before the end of the Obama administration, the imperatives of politics and demography will make it impossible. A “one-state solution,” on the other hand, would make it impossible for Israel to remain the Jewish state without de facto apartheid or, worse, ethnic cleansing.

It’s true that many generations of American diplomats have spent their careers working on the process without producing much in the way of peace, but in some respects the world grew comfortable with that. SNAFU—“situation normal: all f--ked up,” as soldiers used to say—was the default position for American policy. The American public, by and large, lost interest.

But SNAFU was the old normal when predictable dictators ruled the region and, whichever side they were on, they could be held accountable. Since the so-called Arab Spring began in early 2011, what we’ve been looking at is better described by another old military acronym: FUBAR, for “f--ked up beyond all recognition.”

Millions of people across the region are clamoring for change with extraordinary dedication and bravery, growing ferocity, and very little idea, really, where they are headed. In Syria, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Tunisia—throughout the Middle East—there is no “normal” anymore except, irony of ironies, in that good old peace process.

As frustrating as the Israeli-Palestinian issue has been for, oh, about a century, it has a set of parameters and players that are well known to the U.S. and who are well known to each other. By comparison with all the other imponderables on the Middle East map right now, it looks almost simple. In any case, if Obama and Kerry can’t solve the riddle of peace in the Holy Land, then there’s not much chance they can keep the rest of the region from going straight to hell.