Where did you grow up?

I spent my first four years in Washington Heights, at the top of Manhattan, when it was still a neighborhood filled with German-speaking Jewish refugees from the Nazis. We lived between my grandmother Honora’s apartment, a one-bedroom art deco stuffed with formal dark wood furniture shipped from Mannheim, Germany, and my great uncle Lolek and great aunt Gerda’s apartment, a slice of pre-war Vienna beneath the George Washington Bridge. When I was 4-and-a-half, we moved to Texas, where my father worked as an Air Force neurosurgeon. I have vivid memories of my school in San Antonio, my teacher’s blond beehive hairdo and a little blond-bobbed girl named Belinda who was my only friend, joining me in the corner of the playground where I always sat looking out through the chain link fence dreaming of escaping out into the world and back to New York.

When my father got out of the military, we moved back East, and I pretty much spent the rest of my childhood and adolescence around Springfield, Massachusetts. But I would often spend time back in Washington Heights with my German-speaking relatives. I would take the bus down from Springfield and stay first with my grandma and then walk over to Lolek and Gerda’s house. My grandma would explain the world to me with stories about what had happened to her large successful family in Germany in the 1930s when everyone “showed what they really were,” peppered with quotes from Heine and Goethe. But I much preferred the conversation over in Little Vienna at the corner of 181st Street and Cabrini Boulevard, which was much jollier and where they served me endless plates of Wiener Schnitzel and a parade of wandering refugee friends came through the door to tell their tales, their jokes, and to smile and give lots of attention to me, the token American in the room. Mainly I loved to listen to my great uncle Lolek talk and tell me his stories. These involved the end of the world, too, like my grandmother’s—they involved Nazis and knocks on the door and friends betraying other friends and people never seeing their loved ones again—but Lolek’s stories had such a different message: life was infinitely unpredictable, it was funny, it was strange. Death and danger was everywhere but so was life and luck. Lolek’s motto wasn’t “be on your guard” but “be on your toes.” You might miss that crucial opportunity—to escape the Gestapo, to make some money, to eat something delicious, to laugh your head off at a great story, because he only told them once. Because stories have to be “apropos,” they have to come at the right moment, the right sip of wine. If you miss it, though, it would eventually come around again, another day. This was my reason for trying to stay in Little Vienna under the George Washington Bridge as often as possible. I didn’t want to miss any of Lolek’s stories, which were better than television.

What is your favorite item of clothing?

My great uncle Lolek’s old black wool overcoat. As best I can tell, he bought it in the 1950s sometime, but it’s still perfect. It’s the heaviest coat in creation, like it was woven out of metal. I could wear it with just a t-shirt on the coldest day and not freeze. But I really love it because I think of my great uncle whenever I put it on. Somehow the coat just makes me wrapped in his presence, like a little piece of him is still with me. A few years ago, it needed relining, and I couldn’t find a tailor I trusted here, so I took it with me to Italy. My great uncle loved Italy, loved Italians—he’d actually fled the Austrian fascists by going to Florence in 1934, where he lived just fine in Mussolini’s Italy for a few years—and I’d made my first trip to Italy with him as a kid. I was happy to bring his old black coat there to get fixed.

Among biographers I’ve spoken to, about half like to “live and breathe” their subjects, covering their studies with photos, listening to the music their subjects listened to—the biographer’s equivalent to method acting. The other half find this a bit much, and prefer to keep a “professional distance.” What is your approach during the research?

I am definitely of the method-acting school. Everything to me is about sound. I don’t dress up in period costumes or anything like that. I’m very aural. When I’m working, I try to soak up the sounds of an era. I try to impose a kind of musical discipline to keep my mind in the period: I don’t allow myself to listen to any music written or performed after the moment I’m writing about. While writing The Orientalist, I played a soundtrack that alternated between ragtime and Azeri mugams, Russian operas and German and Italian pop songs from the 1920s and ’30s. When I finally finished, I gorged on all my music from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. One of my most persistent, long-term fantasy wishes is not that I could fly or become invisible, but that I could make sound recording be invented decades or even centuries earlier than it was, so I could hear what people in the 1830s or 1750s actually sounded like.

How do you choose the subjects for your biographies? For each book, was there one image or anecdote in the subject’s story that initially drew you in?

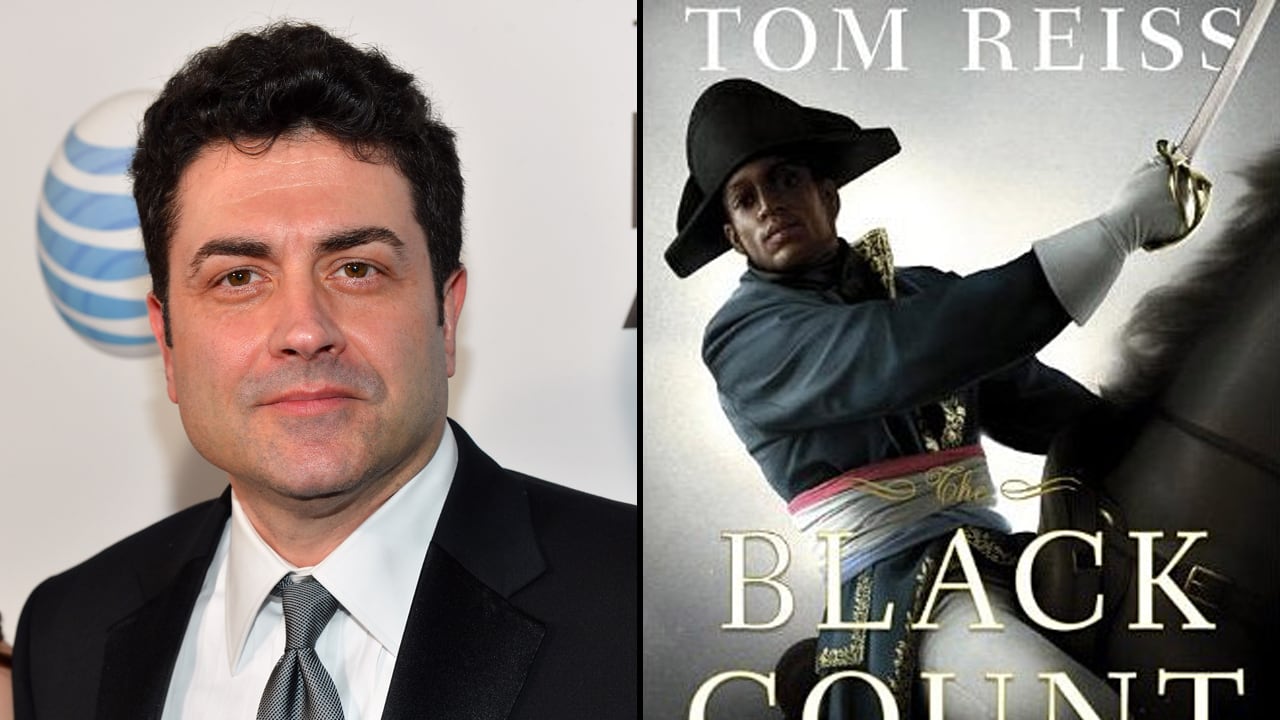

I can’t write a biography of someone just because I admire them or think they had an interesting life. That’s not my métier. I’m a historian as much as a biographer. I’m looking for subjects whose lives are like windows that make us see history in a radical new light. The challenge of writing history is that we feel we know what to expect from the past. I see my job as making history appear as fresh and unexpected as today’s news. I know of no better way to do that than to tell the story of a person who lived through well-known events in an unexpected way. A slave who became the great black hope of the French Revolution and a rival to Napoleon; a Jewish writer who reinvented himself as a Muslim prince and became a bestselling writer in fascist Europe. These characters reveal a surprising side of history. Their experiences as outsiders let me look at seemingly familiar eras through unfamiliar eyes.

What is your favorite snack?

Insanely spicy Szechuan food. Spicy food of all kinds. Dark chocolate and jam and fruit tarts. Enough coffee to send a man to the moon—prepared in all possible ways, at every possible hour.

Do you have a favorite first or last line of a book, one that really resounded for you?

“Those who had no papers entitling them to live lined up to die.” —Jakov Lind, Soul of Wood.

Describe your routine when conceiving of a book and its plot, before the writing begins. Do you like to map out your books ahead of time, or just let it flow?

I begin by writing a section—beginning, middle, ending, it doesn’t matter. I’m looking for a voice for the book. Once I find it, I go back to the beginning and think of how it should unfold. I never outline in advance, but after I’ve written a draft, or a large part of one, I will start outlining on envelopes, mapping the terrain I’ve created and deciding how best to chart a course through it.

What has to happen on page one, and in chapter one, to make for a successful book that urges you to read on?

There should be a problem or mystery whose significance is not clear but promises life-changing knowledge and experience if it is pursued.

Describe your writing routine, including any unusual rituals associated with the writing process, if you have them.

Read everything, go everywhere, indulge in every bad habit. If you are onto a truly great story, it justifies nearly any expense and every vice. There will be time for clean living later. When I’m really deep into a book, I work progressively longer hours, to the point where I’m putting in 16-, 18-hour days. Then the routine is simple: wake up, go to computer, write, break, write, break, etc., until you collapse into sleep just for about six hours, at dawn. Wake up at noon. Stir. Repeat.

Describe your evening routine.

I’m an extreme night owl, so my most intense work time is often after 10 p.m. at night. I generally settle into serious reading or composition then, and by midnight, if I’m lucky, I’m entering another world. If I’m in a period of serious writing and research, I often work until dawn, though I try to go to sleep before the sun comes up, because otherwise I can feel low energy the next day. Still, most of the sunrises I’ve seen in my life have been after staying up all night, and that remains the case now. When I’m not writing intensely, I shift to an earlier schedule—I love daylight, I’m not a vampire; I just can’t get my best writing done then.

Is there anything distinctive or unusual about your work space? Besides the obvious, what do you keep on your desk? What is the view from your favorite work space?

I have a bunch of movie stills: Steve McQueen on the motorcycle at the Swiss border. Multiple pictures of Cary Grant running away from the crop duster. A revolving series of lobby cards from a Louis Malle film called Viva Maria showing Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau dressed as 19th century can-can girls while leading a revolution across Latin America. I have an old advertising poster from my mother’s psychiatric practice that uses a crazed-looking portrait of Napoleon to hawk bipolar disorder medication. I also have tons of espresso-sized mugs with Snoopy on them, in various heroic poses.

What is guaranteed to make you laugh?

So many things make me laugh. When I was kid, I thrived on the Marx Brothers and Woody Allen, Tom Lehrer and Nichols and May. I always had a huge weakness for silliness and slapstick. I loved Danny Kaye, on the one hand, and Monty Python on the other, and the few films of Andrew Bergman. These days I’m hooked on the MADtv sketches—21st century vaudeville available on YouTube at any hour. I think my readers would be surprised how much silly comedy I watch or listen to in between writing my most tragic scenes, but to me, it’s a necessary release.

What is guaranteed to make you cry?

There’s a scene I put at the beginning of The Black Count, where Alexandre Dumas wants to go kill God for killing his dad. I will cry if I look at a picture of my Great Uncle Lolek. He was taken by old age, but I wasn’t ready for him to go. That’s my “I want to kill God” moment. But I also tear up all the time in the movies. I confess I’m kind of sentimental.

Do you have any superstitions?

I believe in forces that cannot be explained rationally. I don’t pretend to understand them or be able to predict them. I think the subjects I write about choose me, for example, not the other way around. Or some cosmic force chooses me. I don’t pretend to understand how. I only try to rise to the occasion.

Tell us something about yourself that is largely unknown and perhaps surprising.

I’m prone to obsessions with songs or comedy routines; it is usually sounds, voices that hook me. I’ll get a certain tune on my radar and play it a hundred times in a week—recently it’s been Billy Joel’s “Allentown,” which I find so oddly poignant. Before that it was “The First Cut Is the Deepest,” the only Rod Stewart song I’ve ever really liked. I heard it in a dream and felt compelled to listen to it—I hadn’t heard it for decades. Now I’ve probably listened to it a 1,000 times in the last couple of months.

I have used this compulsiveness to jump start myself in foreign languages. When I was a kid I discovered my mother’s old record collection and listened to her French chansons again and again. My mother made zero effort to teach me French, but if I listened to her old records enough times, I would begin to figure out what some of my favorite songs meant. Later, when I was learning German, I memorized a song called “Die Gedanken Sind Frei”—“Thoughts Are Free”—that I found on an old 78. It had a very special significance to me because in a TV movie I’d seen, every time an American POW would sing it, a Nazi officer would blow his brains out.

When I decided I needed to learn Italian (to conduct interviews for The Orientalist), I got particularly obsessed with a compilation of Motown artists singing their songs in Italian—the Supremes, Jimmy Ruffin, Edwin Starr. That meant so much to me because you hear how language is all about sounds. Stevie Wonder sings Italian like it was his native language, because he’s completely into the sound of it. When I was younger, I was always told that I had a nearly flawless accent when I spoke a foreign language. That’s actually quite relevant to my writing style. I love listening to people talk—I can just sit at a bus stop or on a barstool and enjoy the conversations going on around me; it hardly matters what they are. It’s the sounds, the cadences, the emotions in peoples’ voices. That’s definitely what got me into writing: the idea of putting all these voices—and the voice in my head—onto paper.

Was there a specific moment when you felt you had “made it” as an author?

My book The Orientalist grew out of a New Yorker piece I wrote called “The Man from the East.” When I published that, I knew I had found my calling and would know how to do it. I didn’t need to wait for to see how it would be received or to sell the book proposal. As soon as I saw the page proofs, I knew this was what I’d been aiming for all along and that it would find its audience. It already had its most important reader hooked: me. I could envision the book I would write from it, and I was dying to read that book, too. I had always written, first of all, for myself—but until that moment, I had always let myself down. Not anymore.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

Take your time. Don’t overproduce. Quality trumps quantity. There are already too many books for the time people have to read them. Make sure yours is worth reading. As a kid, I used to read these paperback armed service editions they sent to soldiers during WWII—classic novels, poetry, crime stories, biographies, history, they were supposed to represent the spectrum of our great freedom-loving culture—and I’d think: what if this was the last book someone read before getting shot? Was it good enough? Or did the poor guy have to read a second-rate novel or a false-sounding biography in his last hours on earth? Luckily, a lot of the material was pretty great. But what if a soldier had my book in their foxhole: would they curse me or thank me? Prisoners around the world have said that reading The Count of Monte Cristo helped them get through their ordeal. That’s something to aspire to. I try to apply what I call the desert island test: if someone were marooned on a desert island and the only thing they had to read was my book, would they cherish it—laugh, cry, think, daydream, reread—or would they throw it on the fire for kindling?

What would you like carved onto your tombstone?

He loved a lot.