The 2004 publication of Irène Nemirovky’s Suite Française, a projected cycle of five novellas about France during the German Occupation, left unfinished when their author was deported to Auschwitz, seems to have inspired a new round of rediscovering “lost” novels, the glory unjustly denied them by the forces of history and the ignorance of editors restored. The success of Suite Française inspired the reissue of a number of novels by Nemirovsky, some of which were popular in her lifetime, but long since out of print, some of which hadn’t been published. But was this because of their lesser quality, as some critics suggested when they were finally brought out? Do we lose our ability to critically assess when dealing with work from the archive?

Nemirovsky’s case is an unusual one. Almost as soon as Suite Française became an international sensation, a controversy broke out concerning Nemirovsky’s alleged anti-Semitism. In her introduction to the French edition, Primo Levi’s biographer Miriam Anissimov accused Nemirovsky of having been a self-hating Jew who subscribed to the idea that “Jews belong to a different, less worthy ‘race,’ and that their exterior signs are easily recognizable: frizzy hair, hooked noses, moist palms, swarthy complexions, thick black ringlets, crooked teeth (…) not to mention their love of making money, their pugnacity, their hysteria.” Those lines were cut from the English edition of the book, and critics in the US and the UK quickly leapt in to develop this point; in The New Republic Ruth Franklin claimed that in the 1930s Nemirovsky used her literary success “to pander to the forces of reaction, to the fascist right,” by appearing in far-right newspapers that published screeds demonizing Jews, and garnering praise for her novels from Robert Brasillach, a notorious Nazi collaborator and strident anti-Semite who was executed after the Liberation. Tadzio Koelb, in The Jewish Quarterly, accused the literary establishment of sensationalizing Nemirovsky’s biography at the expense of doing their jobs; they had “abdicat[ed]” their critical responsibility and rewarded not the work, but the injustice.

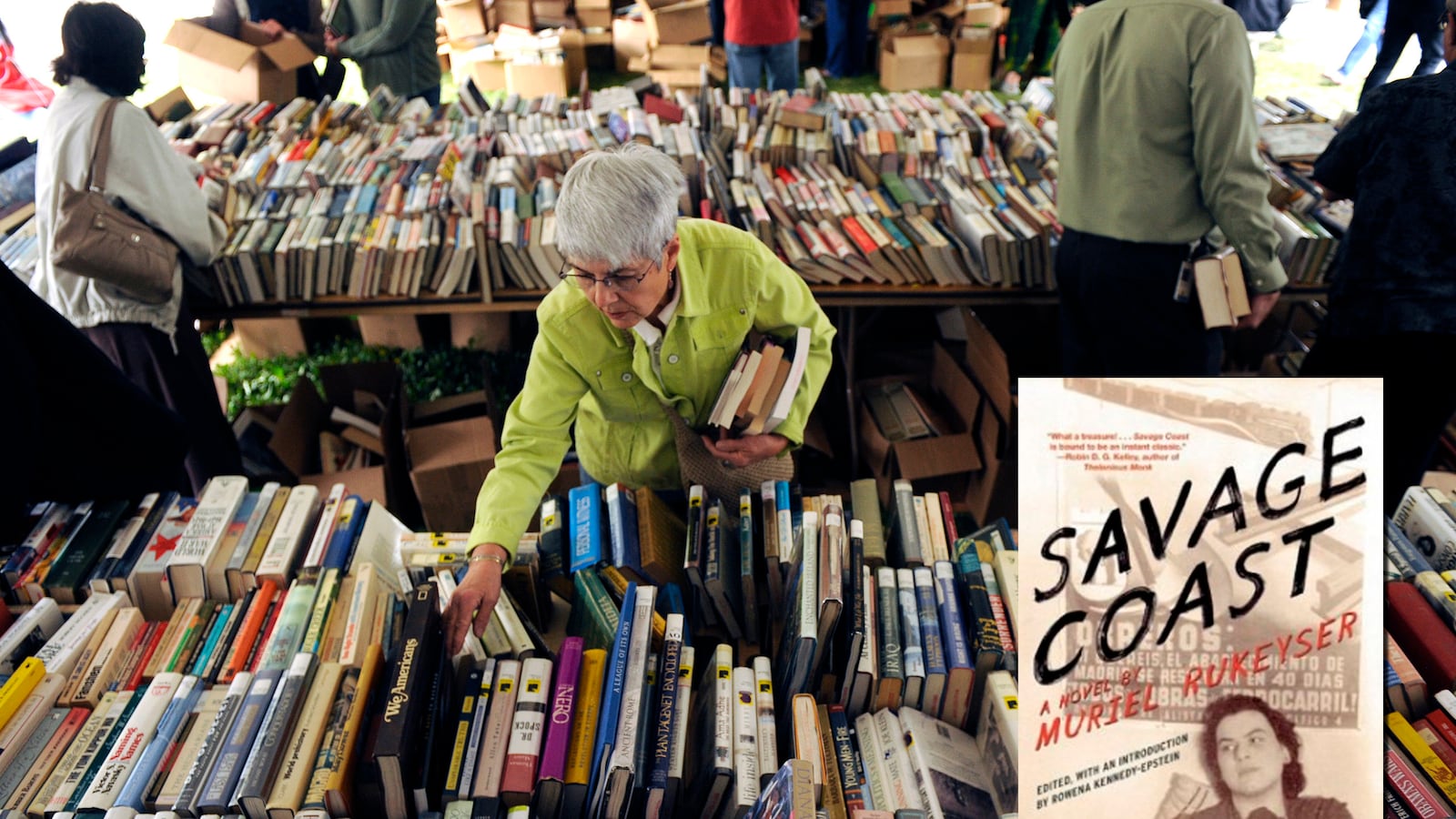

Koelb’s piece raises some good questions. How do we read works that have been kept out of print by a variety of unfair, if not outright criminal, circumstances? To what degree should we let our judgment be influenced by an author’s biography? Two recent releases inspired me to think about attempting to sketch out some answers: Savage Coast, a newly-discovered novel by the great twentieth century poet Muriel Rukeyser, and The Art of Joy, a novel which was considered unpublishable in its author’s lifetime because of its emphasis on revolutionary politics and sexuality, but which has been posthumously greeted as a major work of modern Italian literature. Both are stories of independent women confronting Fascism and the suffering of a people. Both novels were rejected by publishers. Both authors continued to edit their texts, hoping one day they would see the light of day. Should we, or can we, judge them on their own merits? And what does it say about us if we can’t?

The Spanish Civil War inspired an unparalleled body of literature and art. The story of that war is a familiar one, a conflict between the democratically elected Spanish Republic and the military supported Fascists trying to unseat them. Although many countries refused to be drawn in, an entire generation of American and European writers, artists, and intellectuals went there the minute war broke out, convinced (rightly) that the future of Europe hung in the balance. Spain’s greatest poets joined up with the Republic—Lorca, Vallejo, Hernandez—and the Americans and Europeans followed suit: George Orwell, W. H. Auden, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, André Malraux, Laurie Lee, Virginia Woolf’s nephew, Julian Bell, Robert Capa, and Gerda Taro.

Some went to take photos of the action. Some went to be a part of the action. The great American poet Muriel Rukeyser—who at only twenty-two years old had already won an award for her first collection, Theory of Flight (1935)—didn’t know she was heading into a war zone, but it probably wouldn’t have stopped her. Adrienne Rich noted that Rukeyser “was one of the great integrators, seeing the fragmentary world of modernity not as irretrievably broken, but in need of societal and emotional repair.” Poetry, Rukeyser believed, was rooted in the world from which it emerged, and had the power to change it. “Breathe in experience, breathe out poetry,” she would later write.

The daughter of an unobservant middle-class Jewish family from New York, Rukeyser was politically active from a young age, having covered the second trial of the Scottsboro boys for the college paper at Vassar, been jailed for “fraternizing” with African-Americans, and reported on the Hawks Nest Tunnel mining disaster in West Virginia. Her political engagement would continue throughout her life; she was jailed for protesting the Vietnam War, served as the president of PEN, and traveled to South Korea to advocate for the poet Kim Chi-Ha, sentenced to death for political dissent.

Rukeyser was headed to Spain to cover the People’s Olympiad, an alternative to Hitler’s Berlin Games, scheduled for July 19th - 26th in 1936, when the fascist military coup that kicked off the Spanish Civil War took place on July 17th. Although she spent only five days there, Spain would figure largely in Rukeyser’s work for decades to come. What she saw was so profound that she would go on to call Spain “the place where I was born.” It is surprising, then, that so little has been written about that experience, and that much of her writing on Spain remains unpublished.

To celebrate Rukeyser’s centenary this year, the Feminist Press at the City University of New York has brought out Rukeyser’s lost (and only) novel Savage Coast. Although today we can recognize it as an important modernist novel, in 1937 the book was unpublishable, panned in a reader’s report for Rukeyser’s publisher Pascal Covici, who upon reading it for himself called it, among other things, “BAD.” Rukeyser was encouraged to write her impressions of Spain in a brief memoir, and to return to her lyric poetry. The novel was misfiled in a blank folder at the Library of Congress, until Rowena Kennedy-Epstein, a graduate student writing her thesis on Rukeyser, uncovered it, and edited it for the Lost & Found initiative, which devotes itself to publishing unedited or unknown work by major American poets.

The novel is told from the perspective of a Rukeyser double called Helen (Rukeyser’s own middle name), who is traveling across Spain on the Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante train to attend the People’s Olympiad when the war breaks out. For most of the novel she and her fellow passengers (all based on real people: American communists, a South American woman, some women consistently and inexplicably referred to as “the bitches,” and, among others, the Hungarian Olympic team) are stranded in a town called Moncada, and wait, Godot-like, for the train to move, or for someone to come and get them. Eventually someone does, and, via a precarious ride through sniper territory in the back of a pickup truck, the action moves to Barcelona.

An advertisement at the beginning of the novel warns the reader that “This tale of foreigners depends least of all on character.” We must also remember that the novel was written in the throes of modernism; in response to a 1931 review of The Waves, Virginia Woolf noted in her diary: “Odd that they (The Times) should praise my characters when I meant to have none.” They were intended, she said, to be aspects of one consciousness. Similarly, the characters in Savage Coast appear as one group, train passengers, townspeople, fascists and Republicans alike: not morally, but historically, bound together in the same atmosphere of “danger, importance, secrecy.” Languages proliferate—French, Spanish, Catalan, English, prose, poetry, newspaper headlines, song lyrics, official bulletins, a list of the dead—and precisely what’s happening in the plot often is lost in the fragments.

Savage Coast evokes a powerful sensory landscape, as if Gerda Taro were working at a long-duration shutter speed, capturing the movement of light on her photographic paper. In the uncertainty of the political situation, the physical takes on greater meaning: Helen fingers “newfeeling Spanish coin,” and what she can’t put her finger on - physically or figuratively - is most threatening of all. Gunfire periodically ricochets from who knows where: “For a moment they thought it was a new, protracted bombardment, the sound streaked along like a line of sonorous bombs.” Fascist snipers lurk in the hills, and merely sitting in a café could be fatal.

Over the course of the novel we follow as the characters slowly register the gravity of what they’re witnessing, and see Helen herself evolve from tourist to revolutionary. This is (somewhat heavy-handedly) prefigured in one of the earliest descriptions of her: “Her symbol was civil war, she thought—endless, ragged conflict which tore her open, in her relation with her family, her friends, the people she loved.” Meanwhile, the actual civil war is causing death and destruction all around her. “There has never been anything like this,” a townsperson says.

Thanatos soon breeds eros, as Helen begins an affair with another passenger on the train, a German Olympic runner who joins the first International Brigade when they eventually reach Barcelona. These physical encounters transform the landscape into a relentlessly romantic one: “The torrent, mountains demand, steaming night, marvel-black, daring to sweep away, daring to answer, to announce, to find. A radio promulgation, night-manifesto. And the fierce country, blazed across the brain: urgent and cypressed, the granitic cliff, the shock of parent sea. The mouth, strong summer on the mouth,” and later, as Helen visits the town,“The street they entered began with a nougatgreen house. The windowsills being lakeblue and polished, the vivid tiles collected light as the light grew.” “The color is so clear,” Helen observes. “All these pure, warm lights—it is all perfect—the marvelous brightness, in daytime, and the dark fleshy night. I’ve been wanting a country like this for a long time; I thought perhaps there was none.” Luckily, although the affair conflates with the war to create a decisive coming of age for Helen (she thinks “even if she were shot . . . it was all happy for a moment; she was beginning to have a place here … Now is my life, she thought. It comes to this night. Only wait”), it does not take center stage in the novel. Rukeyser manages, throughout, to avoid both sentimentality and propaganda—no mean feat, especially in the 1930s, the heyday of propagandist literature.

But why, we’re bound to ask, did Rukeyser tell this story as a novel, and not as a long poem, as she would tell other stories? What did fiction allow her to do that poetry didn’t? And why does this novel have so much poetry in it? Rukeyser always wanted, Kennedy-Epstein tells us in her introduction, “to write cross-genre and hybrid poetry and prose where ‘false barriers go down.’” Savage Coast shows Rukeyser at the very beginning of that impulse. She was young. She didn’t know yet that she would be a great poet; stories stream out of the young. She believed deeply, as she put it in her poem “The Speed of Darkness” (1968), that “The universe is made of stories,/not of atoms.” Story is at the root of poetry. But “poetry,” she writes in a note to The Book of the Dead, (1938) “can extend the document.”

Savage Coast uses this technique to great effect, especially as the novel builds to its determined, grimly triumphant dénouement. This is most striking when the “official” writing Rukeyser weaves into the novel—extracts from speeches, pamphlets, DH Lawrence’s novel Aaron’s Rod (1922)—causes her own narrative to shift into outright poetry. The result is visually surprising, yet confirms what we suspected all along - the novelist is really a poet. As the delegates gather at the Games in Barcelona to hear a message from the French team, who have gone home, Helen contemplates her own imminent departure from Spain, and her feeling that she—like the French team, like France, like her own country—is abandoning a fight that is only beginning:

THE FRENCH DELEGATION TO THE PEOPLE’S

OLYMPICS, EVACUATED FROM BARCELONA AND

LANDED TODAY AT MARSEILLES . . .

the tranquil voyage, Mediterranean, the tawny cliffs of the coast, cypress,

oranges, the sea, the smooth ship passing

all these scenes, promised for years,

from which they had been forced away

into familiar country, streets they

knew, more placid beaches

PLEDGE FRATERNITY AND SOLIDARITY IN

THE UNITED FRONT TO OUR SPANISH

BROTHERS . . .

the birdflight sailing forced

upon them, so that no beauty

found could ever pay for the

country from which they had

been sent home and the battle

which they had barely seen begun

WHO ARE NOW HEROICALLY FIGHTING THE

FIGHT WE SHALL ALL WIN TOGETHER

The novel is rife with recurring motifs, line breaks, linguistic surprises. Rukeyser hears the echo of “guns” in “slogans,” and in a neat rhyming pair that she never insists on the train comes to stand for Spain, stalled, factionalized, seemingly doomed. If the tone occasionally seems disjointed, or words are leaned on a bit too heavily, we can blame youthful exuberance, the mark of a writer in love with the silent sound of words across the page, and with the discovery of her own powers.

We’ll never know if a mature Rukeyser would have produced more mature fiction, to which we might compare Savage Coast. But then, had Rukeyser not been shamed out of writing novels, she might not have produced the poetry for which she is still read today. Savage Coast is both an unfulfilled promise and an unexpected gift.