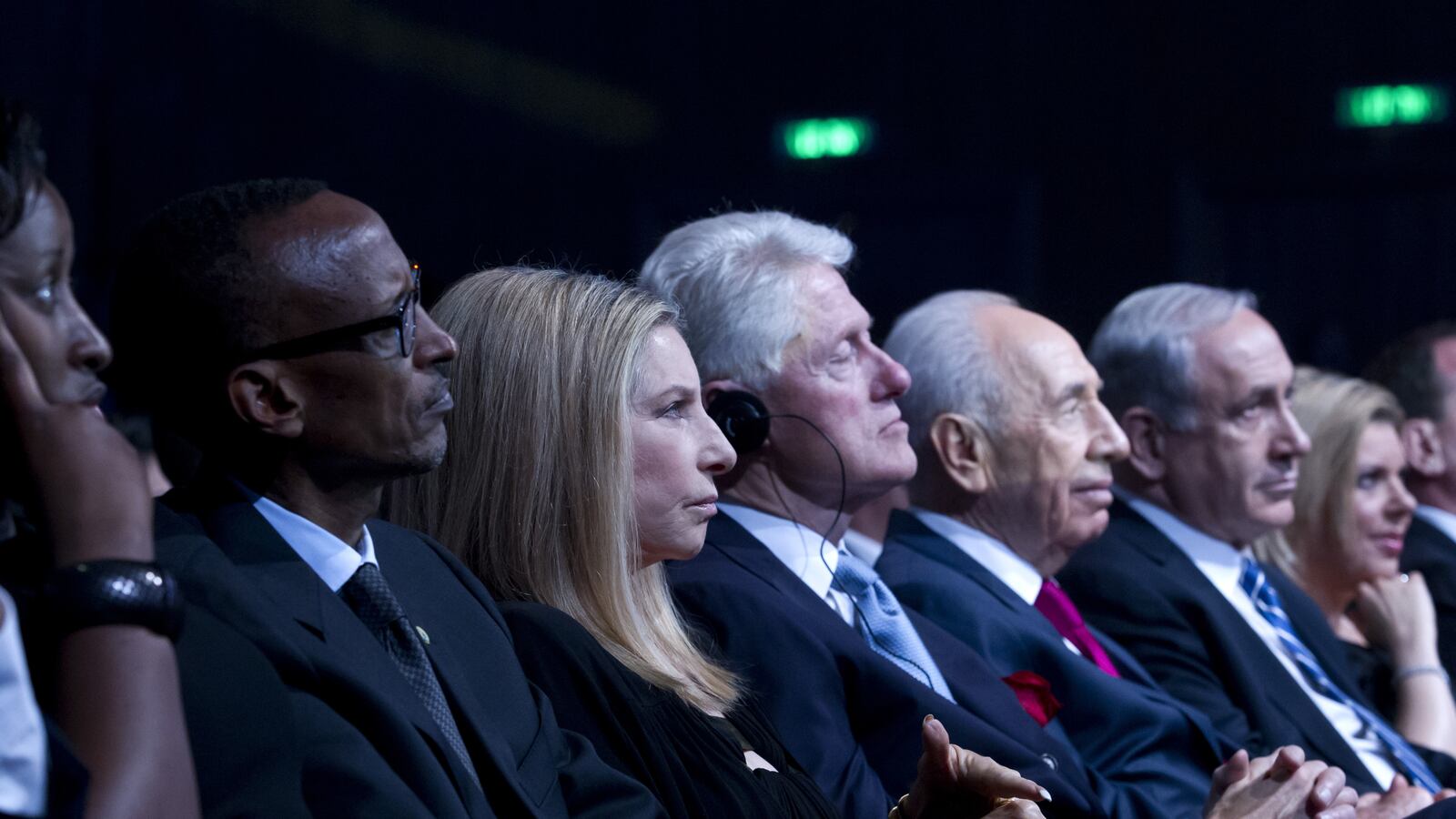

Amongst the guests to Shimon Peres’s birthday extravaganza was the President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame. As leaders of countries that experienced national renewal in the shadow of genocide, the two presidents have much to celebrate as well as mourn. Both Israel and Rwanda live under the signpost of "Never Again," borne by the figure of the survivor amidst memorials of bone and ash. As Rabbi Shmuley Boteach writes in the Jerusalem Post, Israel and Rwanda have "the weight of the world upon them."

For Benjamin Netanyahu and Kagame, this weight will always be measured on the scales of genocide, whether it is the threat of Iran or the incursions from the eastern Congo. "It makes me mad," says Kagame, "when I think about what was done to my people and how Rwanda is misunderstood for protecting itself."

The mutual lessons go beyond the problems of Hasbara, the art of excusing my violence over yours. The symmetries are everywhere, rooted in a politics of vigilante nationalism that reads every conflict as a potential apocalypse. In Rwanda, this collective trauma has been addressed through a process of reconciliation, one which also gives instruction for the challenge of turning weapons into ploughshares.

On the surface, the Rwandan mode of reconciliation, enacted through customary Gacaca tribunals, appears to have restored harmony. The ethnic categories of Hutu and Tutsi that fuelled division and ultimately genocide have been banned. Perpetrator and victim are bound together by a new pact that defines them all as Rwandans. The memorial bones are Tutsi bones, yet those who look upon them are summoned to face the future as one nation.

There appears to be no choice than to remember and forget at the same time. Victims and perpetrators must share the same space, competing for scant resources on every square inch of this land of hills. The person who murdered your parents, or raped your daughter, is now your neighbour. There is no glass booth to separate you.

The bureaucratic management of memory is not an easy project; it depends on too much repression for ordinary people to bear. Beneath the machete wounds of the orphaned and widowed, resentments are silently bubbling. To make matters worse, those cast as murderers—Hutus who constitute the vast majority of the population—are also forced to bury their stories. They are not permitted to speak of that period of colonial history when they were ruled as a servile caste by a Tutsi elite. They cannot mention the Tutsi atrocities in neighbouring Burundi, or the RPF invasions that contributed to civil war. Who knows how many Hutu civilians were killed before and after 1994? To ask the question is to be branded a genocide denier, a crime for which one is imprisoned.

The most dangerous story of all concerns the downing of the presidential plane which triggered the premeditated killings on April 6, 1994. Who was responsible? The Kagame government points the finger at Hutu extremists. Others whisper that Kagame’s army overplayed its hand and must shoulder a portion of the blame for the violence that exploded.

The Rwandan government has an interest in viewing its past through the lens of the Holocaust. It Nazifies the Hutus and thwarts all dissenting questions about the violence of the victims. It frames the RPF’s interventions in the Congo as a necessary war against the ongoing threat of genocide.

It may well be that the truth in all its dimensions is too difficult for the current generation to confront. Perhaps the new Rwanda needs time to heal under the authoritarian hand of one of its heroic generals? Or, will it be too late before all of this repression returns with a vengeance that washes a fresh bloodbath over the Edenic hills of Rwanda?

These threats to reconciliation offer an additional kind of lesson for Israel than the one that marvels at the miracle of the phoenix risen. It would be simplistic to say that if Rwandans can work toward transcending their ethnic differences, so too can Jews and Palestinians. Theirs is an identity that shares a common past, space, language, and religion, and a national myth of harmony from pre-colonial times. Jews and Palestinians carry a story born in conflict and vastly different histories.

But peacemaking will not only be done by drawing lines on a map. It requires an open reckoning with alternate memories of dispossession and independence and of our different accounts of what is sacred and must be shared. It means acknowledging how the targets of violence can also spawn it, and calls on us to mark the carnage that lies beneath the land. The vigilance of victims can be deaf to the cries of others; and the return of the repressed, if it comes armed with machetes or tanks, can be the most destructive force of all.