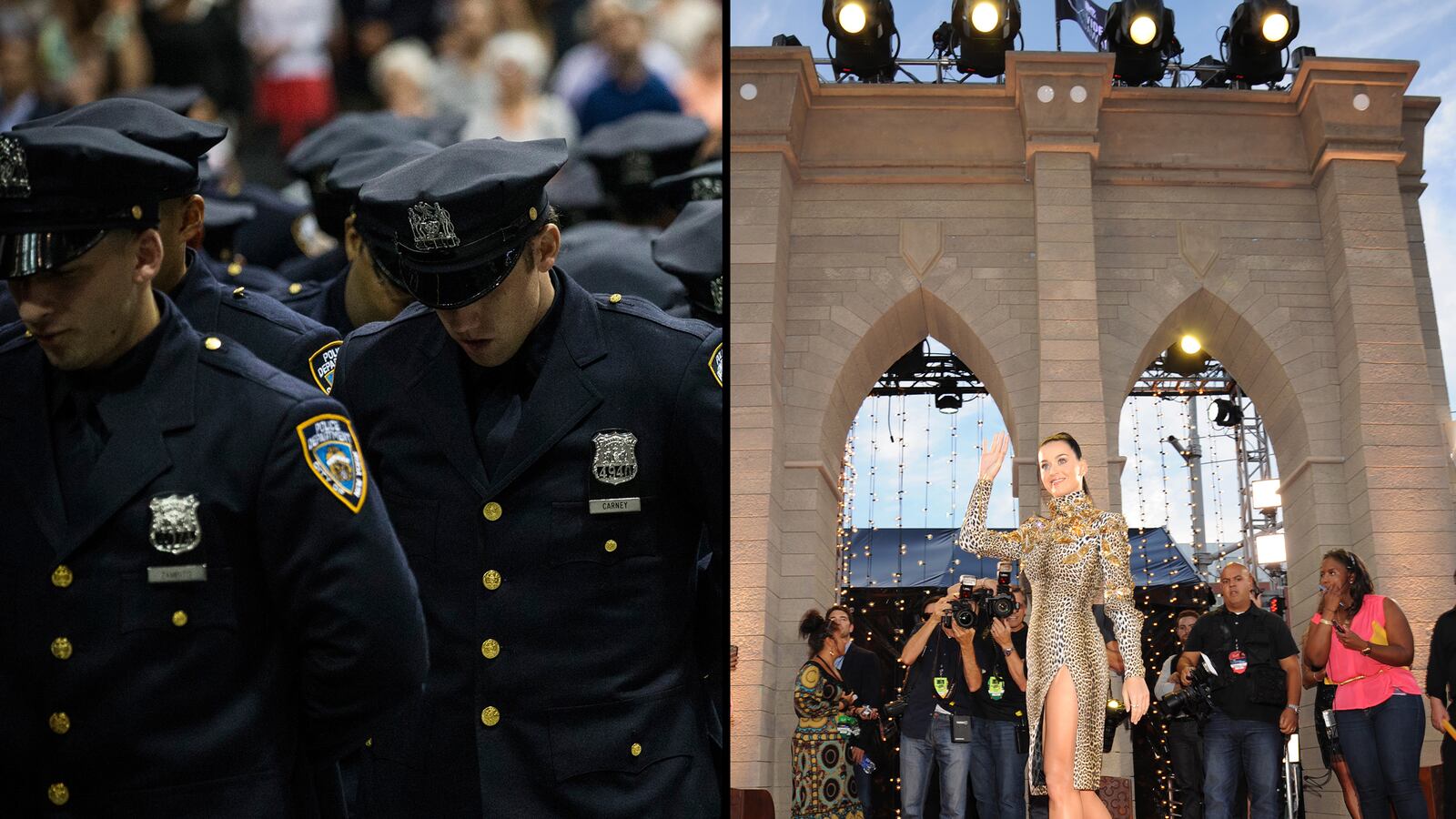

Where the blood of shooting victims once stained the pavement, there was now the red carpet of the MTV Video Music Awards.

And as everybody from Justin Timberlake to Taylor Swift to naughty Miley Cyrus strode across into the new Barclays Center on Sunday evening, the camera flashes were from paparazzi rather than from crime-scene photographers.

But the real stars were the cops who have transformed New York into the safest big city in America and turned this once crime-ridden corner of Brooklyn into the venue where more tickets are sold than at any other place in America.

“With safety and security, everything is possible,” Mayor Michael Bloomberg said last month at a police-academy graduation in the same arena. “Without it, nothing is.”

Compare Miley Cyrus to a cop such as 28-year-old Kevin Brennan, who last year refrained from shooting a Brooklyn gunman for fear of hitting innocent people and then was himself shot point blank in the head. He somehow survived and returned to the scene this year to help prosecutors prepare for the gunman’s trial. He was there when he and his partner spotted two men who were wanted for an unrelated robbery, and Brennan did not hesitate to join in making the collar. He had one of the men up against a fence when he felt something too familiar in the waistband. He recovered a loaded 9mm, one of thousands upon thousands of gun collars cops have made in an unceasing effort to keep the city safe at their own peril.

Yet instead of being honored for their remarkable achievement, the cops find themselves being accused of rampant racial profiling and gross violations of civil rights with aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics.

The implication is that they are a bunch of racists out there trampling on the very Constitution they swore to uphold. The truth is that even the plaintiffs in the federal suit against the NYPD acknowledge that 90 percent of the stops were justified. And at least some of the excesses among the other 10 percent have been the result of bosses who have become obsessed with numbers.

One indisputable fact is that the cops saved the city. And scarcely anybody seems to feel obliged to thank them. Were they not the cops they are, they might just let the city slide back into bloody mayhem. But word that somebody is in distress will still bring them running, propelled by what a veteran cop on Monday described as the main reason most of them join the NYPD in the first place.

“To help people,” he said.

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the great March on Washington, it is worth remembering that there would have been no march at all, had two New York City cops not saved the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. after a deranged woman plunged a letter opener into his chest. The sharpened point was a fraction of an inch from the great man’s aorta, and he almost certainly would have died that day in 1958 if police officers Phil Romano and Al Howard had not stopped a panicked onlooker from attempting to extract the blade. The cops gingerly transported King to a hospital, rightly guessing that the slightest jostle could have proved fatal.

Afterward, King and his wife did thank the cops for saving him. Romano and Howard said they were just doing what cops are supposed to do.

Other cops have done much the same countless times since then. A few cops may have been brutal, and a few may have been infected with the racism that King rightly viewed as a national sickness, but they always answered a call for help, no matter how dire the danger, too often at the cost of their own lives.

As New York’s murder rate rose to some 2,000 a year in the early 1990s, it became clear that just responding was not enough. A crime-fighting genius named Jack Maple devised CompStat, where commanders regularly had to stand before a computer-generated map of crimes in their precincts and report what specifically they were doing to address any patterns or trends. The name CompStat derived from from the computer statistics program used to generate the original maps. But the emphasis was on smart and imaginative tactics and relentless follow-through. The only really important numbers were supposed to be crime stats, particularly murders.

And with the help of CompStat and more recent strategies, the number of murders eventually fell from more than six a day to less than one. The results were so good that the top brass who came after Maple grew increasingly obsessed with numbers in general. The bosses began to measure not just crime, but individual cops, issuing them “activity sheets.”

Where cops such as Romano and Howard were once trusted just to do their jobs, present-day cops had to keep daily, weekly, and monthly tallies of their “activity,” including the number of radio runs, arrests, and summonses, as well as how many times they stopped, questioned, and frisked people.

The stops-and-frisks were recorded on a Unified Form 250. A supervisor would be heard telling his cops, “I want 250s!” whether or not they happened to encounter anybody suspicious enough to justify being frisked. The cops would comply only for the supervisor to demand the same number or more the next time. A cop who came in with fewer was liable to be told his activity was slipping and instructed to go out and get more.

Otherwise, the supervisor’s supervisor might demand to know why the total number of 250s was down. One sergeant recently became so desperate that he went out himself and stopped passers-by, taking enough info to complete the forms.

The increasing reliance on numbers has been accompanied by a decreasing reliance on true leadership. The official message to cops was “Do your job,” but it really was “Keep your numbers up.”

The underlying formula was that more activity means less crime. And nobody can rightly deny that one result of these thousands upon thousands upon thousands of frisks was to make people more cautious about carrying illegal guns. Even so, much the same result may have been achieved if cops had simply been trusted to follow their instincts while staying within the bounds of reason and the law.

As it was, the unrelenting pressure to keep up their “activity,” particularly in the higher-crime areas, resulted in so many frisks that the department that had once saved King was accused of the wholesale violation of civil rights. The NYPD will soon find itself with two outside monitors: one appointed by a federal judge to ensure the stop-and-frisk tactics are within particular guidelines; the other instituted by the City Council to oversee the operations in general.

Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly have said such micromanagement of the police will surely result in more murders. Cops agree, though they also note a certain irony. In their view, they have been micromanaged by the department itself.

Meanwhile, the federal judge, Shira Scheindlin, has gone so far as to order cops to wear body cameras in the precinct in each borough that has the highest number of stops-and-frisks. Never mind that street people are leery enough about being labeled snitches without having to worry they will be videoed giving cops tips.

At least good cops, and that means the great majority of them, will be able to use the cameras to protect themselves now that the City Council also has passed a law making it easier for civilians to sue if they believe they have been subjected to racial profiling.

All of it, from the court orders to the activity sheets, amounts to an insult to such cops as Kevin Brennan.

If you want to be scandalized, think of that, not Miley Cyrus grabbing her crotch.

No matter how you feel about stop-and-frisk, anybody who even visits New York owes two words to the cops who made the city so safe, there is a red carpet on a stretch of Brooklyn pavement that was more than once stained red with the blood of shooting victims. I join in saying those words as someone who once had a guy with a knife try to stab me at that very corner.

“Thank you.”