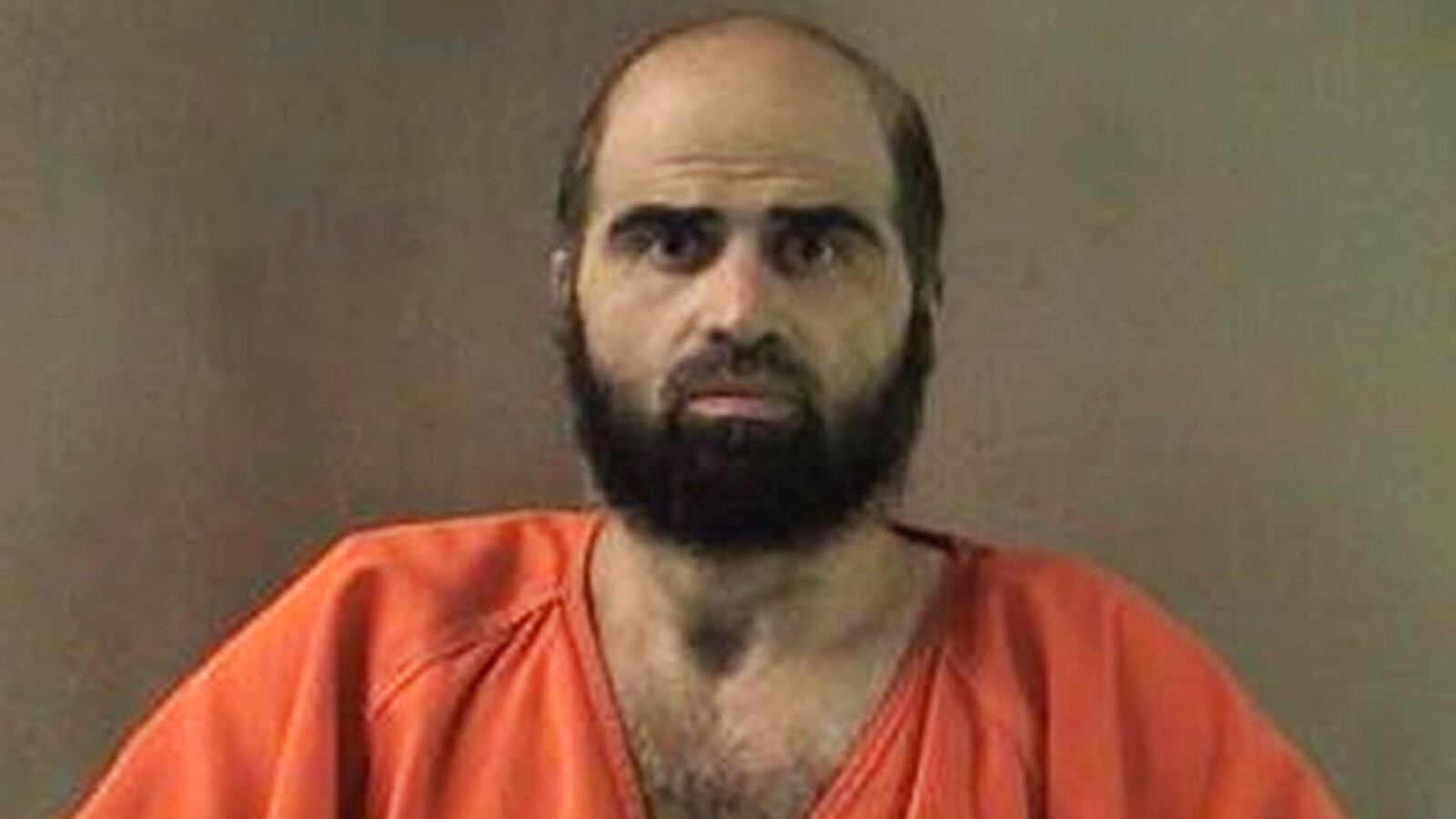

After only two and a half hours of deliberation, on Wednesday a jury recommended the death sentence for Nidal Hasan, the Army major convicted Friday on 45 counts of murder and attempted murder. The matter will now be reviewed by the court-martial’s convening authority, Lt. Gen. Mark Milley, who can either accept the death sentence or impose a lesser punishment of life in prison without parole. After Milley’s review Hasan will have the opportunity to appeal, and President Obama would have to sign off on any military execution. Five soldiers currently sit on the Army’s version of death row, but none have been executed since 1961, when a private was hanged for rape and murder.

I am glad I do not have to decide Hasan’s fate, but I believe death is not the best punishment for him. Because he has expressed the desire to be martyred, military justice ought to deny him that wish. I realize that I can only say this from a comfortable distance, unable to comprehend how my views might change if Hasan had killed one of my loved ones. His crime, however, did hit home in the literal sense—when I was in the Army, I was stationed at Fort Hood.

On the day Hasan went on a rampage, I heard the first sketchy reports of a mass shooting and immediately assumed a soldier had done it. From the safety of my apartment in Austin, just an hour’s drive but worlds away, I turned up the radio. The commentator on NPR speculated about whether this was an act of Islamic terrorism. I thought not. Knowing something about the security protocols in place on post, I believed it was unlikely that a jihadi could gain access without being stopped at the front gate.

A disturbed soldier, on the other hand, might easily be waved through without being searched. A disturbed soldier, and not al Qaeda, seemed the most likely explanation for a spree killing on a military base. And this was not just any base but Fort Hood, which along with the surrounding town is home to the largest concentration of people anywhere in the world, outside Afghanistan and Iraq, who have fought in Afghanistan and Iraq. Hearing the news that the shooting had occurred at a soldier-readiness center, I further assumed the gunman had been previously deployed to one of those war zones and was about to be sent overseas again.

Without even thinking about it, in my anger and grief I had fallen back on the “crazy vet” stereotype to make sense of things. Of course, I was half-wrong. Maj. Nidal Hasan had not honed his grudges or developed his murderousness overseas. He was not a combat veteran at all. Only a very oblique definition of wartime trauma can possibly explain his actions. Hasan, it turned out, was a strange set of contradictions: an Army officer and an al Qaeda sympathizer; a doctor and a destroyer; a sensitive man who relatives said mourned for months over the death of a pet bird and now a convicted murderer.

As his court-martial finally got under way, I was reading a book called Making War at Fort Hood. I came to it skeptically, not really sure if a civilian academic (the author, Kenneth MacLeish, is an anthropologist) could provide me with any new insights into soldiering. After all, I had been there, done that, and at Fort Hood, no less. But to my surprise, reading MacLeish’s work I felt like I understood my old home better than I had while living there. To really know something, I’ve found it is hard to overestimate the benefit of time, mental distance, and a fresh set of intelligent eyes.

MacLeish conducted a year of fieldwork in central Texas, and it shows in his descriptions of Fort Hood and its milieu, which are full of faithful and telling details. The concentration on place should not come as a surprise, since MacLeish engages in ethnography, a type of research that in the past has focused on chronicling “exotic” or non-Western cultures with an emphasis on describing their physical environments and ways of life.

I am heartened that someone in MacLeish’s line of work and with his considerable skills has devoted this much serious thought to military culture. At the same time, I am troubled that the military has become so divorced from the mainstream experience of a nation at war that an ethnographic anthropologist would consider it a worthy subject of study. Clearly, an entrenched warrior caste now bears the burden of our fighting.

To its great credit, MacLeish’s project refuses to paint soldiers as either noble heroes or unwitting victims, two of the most dominant and therefore the most tired archetypes of our time. In a society that has exoticized and abstracted the military, MacLeish re-humanizes it. He is also remarkably precise in how he describes the institution of the Army: how its various bureaucracies, all geared at least tangentially toward killing people and destroying property, prescribe and encompass so many aspects of a soldier’s life, from the most consequential to the seemingly benign, such as haircut styles and family day picnics.

MacLeish’s book is smart, necessary, and insightful. If I have a bone to pick with it, I worry that it will mostly appeal to his fellow academics. I wish for his next project that he would adapt Making War at Fort Hood or write a similar work for a popular audience. Not that being popular is necessarily better, but as many people as possible need to read a book like this one. It is that vital, and so its diction and narrative structure ought to be addressed to the average American, who so relies on the military for a sense of national identity, but who so little understands its workings.

In his postscript MacLeish tells the story of a woman stuck in a traffic jam at Fort Hood’s front gate when it was closed in the immediate aftermath of Hasan’s rampage. The woman, whose husband was stationed on post and who knew no details of the shooting, jumped to the same conclusion I had when I first heard about it. She got out of her car and said to a reporter, “I expected it someday. I’m not shocked. We’re not invincible, and our soldiers need help without stigma.” MacLeish remarks on the woman’s unflappability—how unsurprised she was by the violence—and then he goes on to conclude that Fort Hood is a place where everyday life, and the continuous war that organizes it, “simply does not yield to the melodramatic temporality of tragedy.”

We should be careful, even while mourning Hasan’s victims and when contemplating his punishment, not to yield to this same melodrama. It is a sensibility that inspires many repugnant things, including rampage killers. Despite their differences, all these men seem to want the kind of immortality that comes from infamy. They crave the spectacular drama of innocent death, and their evil calls to mind names like madman, maniac, fanatic, and monster. Each word, however true, falls too short and comes too easily. Rather than use metaphors that point toward nightmare, we would do better to turn our gaze to nightmarish reality itself. Kenneth MacLeish’s definitive study of life at Fort Hood, an existence by turns mundane and hideously violent, is an excellent place to start.