Bruce Weber is having a moment.

The legendary fashion photographer and filmmaker -- whose work you'd recognize from countless magazine spreads from the last three decades -- travels this month to the Venice Film Festival, where he shows two of his stunning film works.

The first film he made was Let's Get Lost in 1988, a touching, black-and-white portrait of the jazz musician Chet Baker. The film, which turns 25 this month, will be shown to crowds in Venice on Saturday. It follows Baker, a seductive and self-destructive trumpet player, as he plays packed venues, wins over women -- and then, after a long struggle with drug addiction, reflects back on his life right before his death.

ADVERTISEMENT

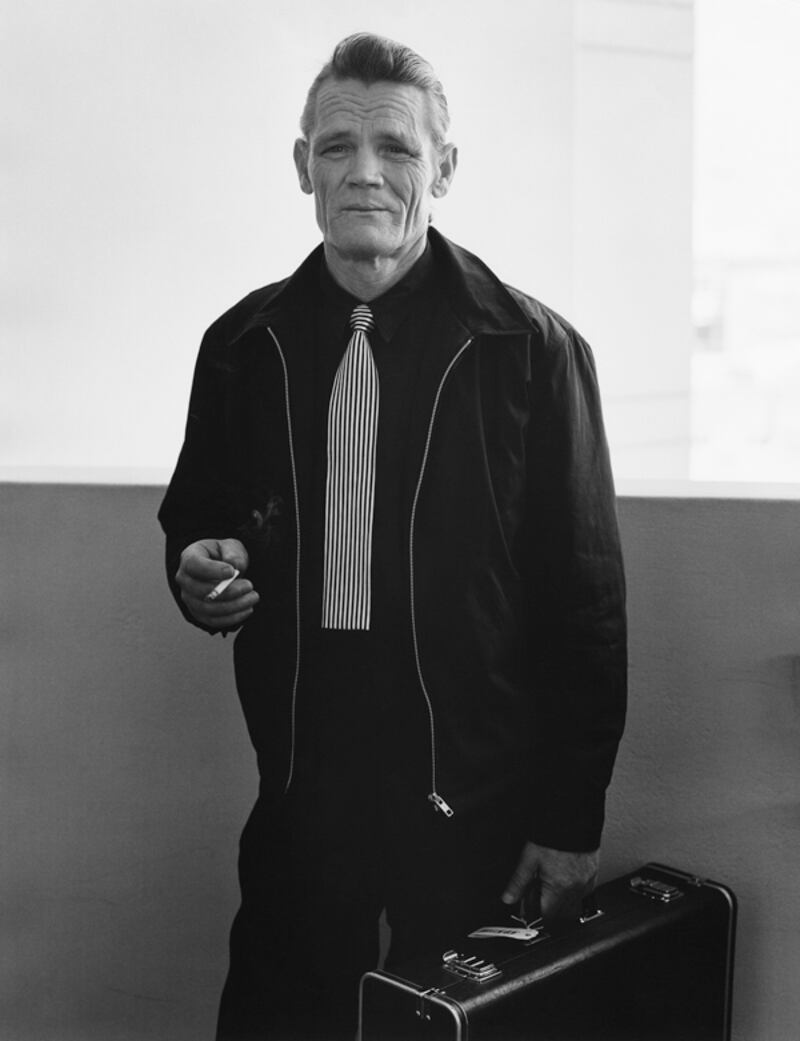

In Venice, Weber will also debut thirty minutes of Nice Girls Don't Stay For Breakfast, a work-in-progress about the handsome and reclusive Hollywood "bad boy" Robert Mitchum that Weber has been working on for the last 15 years.

We spoke to Weber on the occasion of the Venice Film Festival about both film projects -- and his memories of the two great men.

(This interview has been edited down from its original version.)

How does it feel for Let's Get Lost to be 25 years old now?

Weber: Well you know, films are like your babies. You raise them and some go to college and some go out on the road. [With Let's Get Lost], I’ve always felt that we didn’t go to college -- we just went out on the road. It's nice that it has had this long history and I’m really proud of it. I'm moved to be able to see it again, and see all the good things and the mistakes. I think that sometimes the mistakes that you thought you once had were really the strong points.

Really? What jumped out at you as a "mistake" that is now a strong point?

So much has happened to so many people who worked on this film, and so it's almost like looking back on a yearbook and checking out your friends' signatures. When I look at it, I see a lot of new things in it, but what’s really surprising to me is to see how Chet [Baker] just grows on you. And by that I mean it's that he’s kind of contagious, and very seductive, and that power that certain people have is extremely strong. That's the thing that I really feel good about that’s really strong in that film. We didn’t have any money when we made this film, and in a way that’s kind of a good part about it because it has a rawness about it. I think if I was doing it again today, and Chet was alive, I would do a little epilogue and go to visit him at his little beach house by the sea. You know, with his trumpet and his dog and his girl.

Chet was a reserved man, and you really drew him out over the course of the film. Do you have any memories of the time you spent speaking with him?

At the beginning of film we were talking to him at the Shangri La Hotel in Santa Monica, and he says something about going out to California and driving with his dad and picking oranges from trees. We had gotten some dirt in one of the cameras and we heard this crazy sound, and I just said 'Cut!' I said, 'Chet, could you wait a second? We just have to reload.' And he said, 'I cant do it again, I’m a jazz musician!'

It's funny, when he said that, I didn’t understand it. But the more documentary films you make, or any kind of films or photographs you make, you can't do things again sometimes. It doesn’t work that way. One film also leads to another. When I made Broken Noses with Andy Minsker, I used a lot of Chet’s music. Andy looked a lot like Chet, so then it was natural that I would do a film on Chet Baker since Nan [Bush, Weber's wife and collaborator] and I always loved his music.

Is it true that you first became interested in Chet as a subject when you saw his photograph at age 16?

Well, Bill Claxton, a wonderful photographer, had photographed me a lot when I was going to school in New York, and I was at film school, and I realized that Bill had taken this beautiful picture of Chet Baker on the back record sleeve of the album Let's Get Lost. And I just took this record album with me everywhere I went, I just carried it with me to prep school, through college in Ohio, through NYU film school. If I went away, I took it with me. It was like my teddy bear. Bill’s photograph really struck a chord in me. But when Bill photographed me, I didn’t look anything like Chet Baker.

Looking back on Let's Get Lost now, 25 years later, what do you see? What do you feel you've learned from it?

You know there's not a film you make, or a photograph you take, that you don’t learn something from it. You know, people look at these things and they think they look so easy -- and they should look easy -- but they don’t. When I work on something, I want it to be worth it. In that sense, I'm not talking about being a success or making a lot of money. I'm just talking about, is it going to mean something to me and all the people in my crew who worked on this film in 25 years? [Will] they be able to look back and it’ll be their own personal record of that time in their life?

You know, when you make a film on somebody, you’ve kind of adopted them for good or for worse. You just have to say at one point, look, I love you but I'm not in love with you. I have to make the film that I have to make. I think as long as you're true to yourself, then you're showing them a lot of respect by making a good piece of work.

Your upcoming film, Nice Girls Don't Stay for Breakfast, is a portrait of the actor Robert Mitchum that's not unlike what you did with Baker in Let's Get Lost. Can you draw a line between the two men?

Oh, definitely. The whole time of [Let's Get Lost] Chet and I always talked about Bob Mitchum. They [both] have such an irresistible bad-boy quality to them. And they’re the kind of guys that girls just can't help but fall in love with and wanted to care for them. Bob was a lot like Chet in a lot of ways. He was really smart, he was extremely well-read. There aren’t very many characters left in the world; Bob really had that spirit, he was such an individual, and very different. I never met a woman who didn’t meet these two guys and say to me the next night after dinner, they’d call me and say, ‘Oh, I've been thinking about him all night and I've been wondering, how he is today? Is he okay? Do you think I should call him and check up on him?’

How did you get Bob to say yes to you making Nice Girls Don't Stay For Breakfast about him?

Tina Brown had given me this assignment for Vanity Fair to photograph "Tough Guys," and so we were in Montecito photographing Stuart Whitman. It was a wonderful assignment, the kind that photographers don’t get everyday, and I was really excited. Stuart Whitman said to me and my team, 'Well, what are you guys going to do next?’ And we said, 'Well, we're going to go across the street and photograph Bob Mitchum.' And he said, 'Well, good luck, is he there?' And we said, 'Well, yeah, we hope so!’ He said, ‘Oh boy, I gotta hear about this one.’

So we go over there and we're in this van and I go and knock on the door. I thought, I’m just going to walk away because he’s not there! And finally his head peered around and he said to me, "Mmhmmhmm?" and just sort of mumbled. And I said, ‘Hi! I’m Bruce Weber. I’m here from Vanity Fair. I’m supposed to see you right now at 2 o’clock. How are you?’ And there was about a three-minute pause. I’m just standing there staring at him and he’s staring at me, and he goes, ‘Worse.'

So I mentioned a mutual photographer who’s a friend of mine and a friend of his. I said, 'Oh I’ve heard a lot of good things about you from him!" And he said, 'Do you believe everything that guy says?'

And I said, ‘Well, truthfully, no.' And he said, 'Well, alright then, come on in.'

I went into his library and Bob sat on a La-Z-Boy and I was sitting across from him and I said, ‘Bob I have some friends in the car, do you mind if they come in?’ ‘Yeah, yeah why not.' So I went out to the car and got [the crew]. I said okay this is going to like really flip him out, he was wearing these really funny jeans that a lot of older guys out in the west wear, they were really high-waisted, and I thought they just didn’t fit him well because he’s a big robust guy. And I just thought they weren’t like really old enough to be great, and I just thought, I don’t want him to be wearing these jeans. So I said to him, ‘Bob, could you change your pants?' And the whole room went silent. And he said, ‘What?!’ and I said 'Well, I was just thinking maybe you could put on a pair of old khakis.' And he stared at me for the longest time and then he said, ‘Yeah, sure. Why not?'

And so we went out to his pool, and he says, "I haven’t cleaned this pool in six months." He says, 'Everybody thinks that because I have a place in Montecito, I've got a big ranch and a lot of acreage. I don’t. I've got a simple house and a two-car garage and a dog and a pool that’s not clean." And he’s sitting there smoking Pall Mall, and he became the man who was in all of his movies in front of me.

Later, I was talking to Nan and I said, ‘You know, I really want to make a film on an actor. I’ve always wanted to do it, and I’ve got to do it on Bob because he just reminds me so much of my dad.'

So every job I did, whether it was Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, whether it was for Vogue, French Vogue, Italian Vogue, British Vogue, I ended up in Santa Barbara. And I would stay at the Four Seasons Hotel, and I always had a beautiful girl working with me. And at the end of the job I'd say, 'Can you do me a favor? Can you take these books up to this friend’s house? He’s a swell guy, don’t worry he’s not going to do anything to you. Just ring the bell and say this is from me and -- I'd put a note in it, or I'd send him a huge cake or I'd send him videos I thought he’d like or CDs I thought he’d like, saying: Bob, I want to make a film on you. And he never responded.

Finally, I sent him Let's Get Lost, and he called me and he said, 'I really like this film.' And I was surprised, because he never talked about anything he liked, you know? Anyway, that was pretty great. So he said, okay!

But we never could get a date from him. Which is so Bob, you know? So finally, I just called him and I said, ‘The Beverly Hilton Hotel, two weeks from now, on a Thursday. We’ll arrange the car.” And he said, 'Oh don’t bother arranging the car, I’ve got a buddy who works down at the gas station and he’ll just drive me up in his Wagoneer.’ And that’s how it started.

How much time did you spend with him?

Every couple months I’d get together with him, when he wasn’t doing something in Europe -- you know those days he was making a lot of films in Europe -- or I’d go out and just see him. He never said no to me about anything. The only time he said no to me was when I said, ‘Bob, lets all go down to the pool and all go swimming.’ He said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘Lets go swimming in the pool here.’ He said, ‘I haven’t been in a bathing suit in 30 years!’ He didn’t say no, but I just understood that he really thought that was weird.

He was kind of an amazing guy that I felt really lucky to have encountered in my life and to make a little film on. Bob was the kind of guy that a lot of different generations of men wanted to grow up to be like. And yet, nobody knew that inside, there was this sensitivity. It's something that I’ve always admired in both men and women that I’ve photographed who are very strong.

Chet used to say that he always liked to get a hotel room or a motel down by the train station or bus station for an easy get-away. Bob used to say that when he’d go to a new town on location, he said, 'The first people you always try to meet is the chief of police and a blonde.'

And so when I travel, I always think of these two guys saying this, and I start laughing, because today our lives are just so different -- when we get to a location now we’ve got to start working right away. We don’t get a chance to meet the chief of police or a blond. So I think about that and laugh.