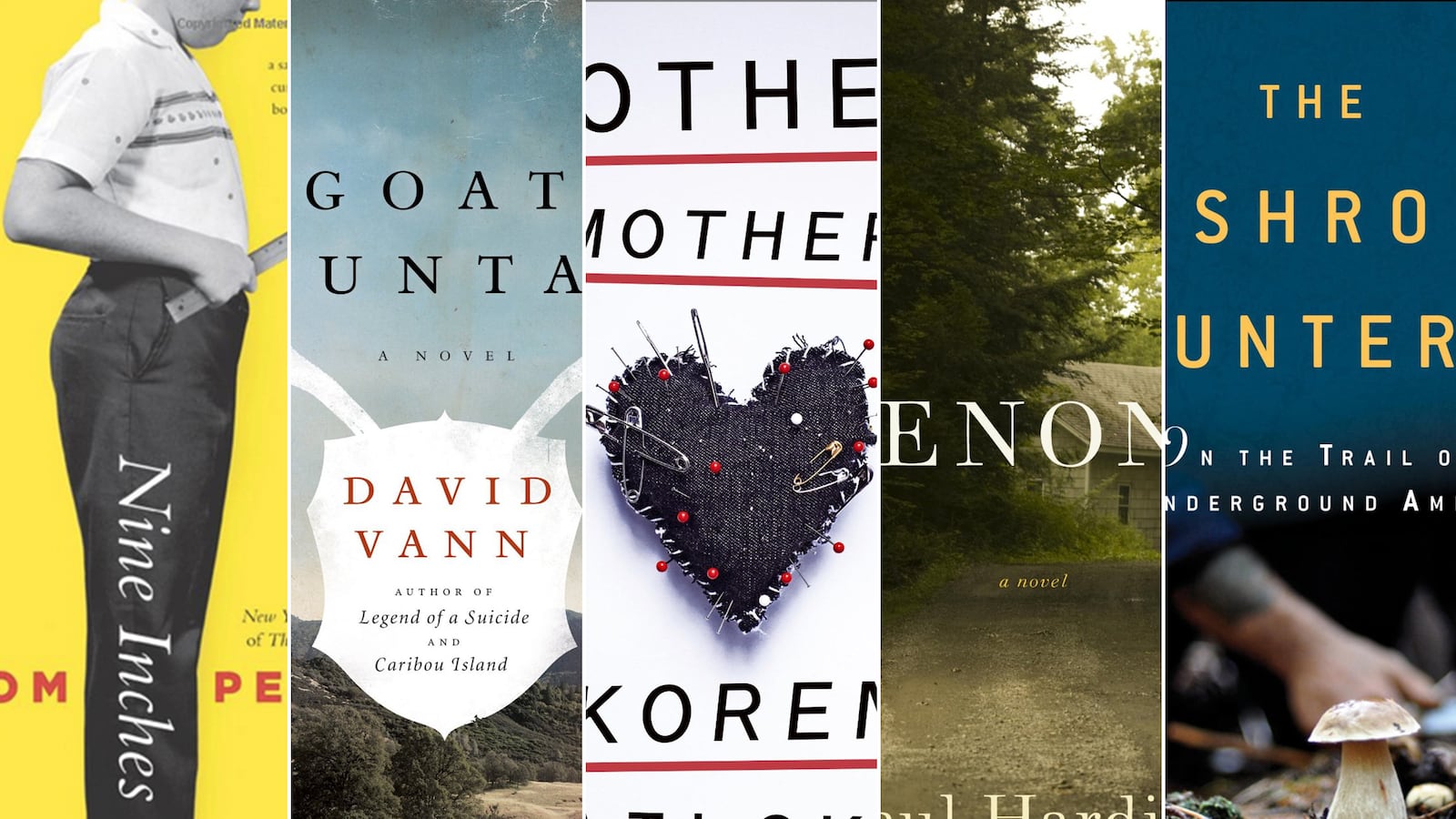

Enon by Paul Harding.

Returning to the town of Enon and to the Crosby family of the Pulitzer-winning ‘Tinkers.’

If adapted for the stage, this novel would make an artful, off-Broadway monologue. We return to the town of Enon and to the Crosby family, which were the subjects of Paul Harding’s debut novel Tinkers, winner of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize. In the wake of his daughter’s tragic death, Charlie Crosby is crazy with grief. For one full year, we never leave his side. Not that we would want to. Even in his sorrow, Crosby is a charming raconteur, and early on one sees that Enon is the stage on which the drama of his broken heart will unfold. The rest of the cast members are ghosts. There is his daughter, who haunts his every hour. There are the painkillers, which he needs in growing numbers. And then there is Enon itself, whose dynamic landscape threatens to overwhelm him: “Some early mornings I could almost hear the echo of the last gears of the stage clicking into place as the swoosh of the first sunlight ignited across the fairways and rushed down toward me at the outskirts of the golf course on the near side of the cemetery.” As Crosby’s addiction deepens, he experiences strange hallucinations that enlarge the scene and propel the plot. He burglarizes an elderly neighbor’s home in search of drugs, wakes up high beside his daughter’s grave, and casts a fly rod off a stump in his backyard. Unaware he’s being watched, his desperate actions assume a transcendental beauty, like a mystical one-man show on memory, grief and time.

Goat Mountain by David Vann.

A boy kills a poacher, whereupon his father and grandfather argues about what to do.

One may not hope to like a novel’s characters, but one certainly hopes to know them. Goat Mountain begins when a boy, who’s only 11, goes hunting on his family’s land with his father, his grandfather, and a friend. The boy is determined to kill his first buck, since this would make him a man in the eyes of his elders. Instead, he finds a poacher, raises his rifle, and fires a lethal blast. He feels no remorse. “There was no thought … there was only my own nature, who I am, beyond understanding.” From here, what seems like a coming of age story devolves into Lord of the Flies-style anarchy. The men return to camp, string the dead man up by his ankles, and then come to blows about what they should do: dispose of the body—or dispose of the boy? Meanwhile, other questions gather, like who is this boy and why did he kill that man? What experiences have shaped him and his family? Because these questions are never addressed, the characters seem witless, flat, and mean. Indeed, man’s bestiality is the central theme of this book. The boy finally does get his buck, but he botches the killing, and when the animal suffers needlessly over the course of many pages, so do we. It’s not just that these characters are unlikable. It’s that who they are and what they do remains unknown.

Nine Inches by Tom Perrotta.

Stories of overachievers and privileged adults who get within inches of the American dream.

Suburban satire is Tom Perrotta’s specialty. In his novels, Election and Little Children, which later were turned into movies, Perrotta zeroed in on the competitive spirit that lurks beneath manicured lawns and picturesque homes. He returns to these themes in Nine Inches, a collection of stories that unzips the American dream, and pulls out all the stuffing. Some readers will groan: we’ve heard this story before. Why should we care about arrogant overachievers and the sadness of privileged adults? In the hands of a lesser writer we probably wouldn’t. But these are some sharply drawn stories, fleshed out with three-dimensional characters, withering satire, and genuine pathos. We encounter an aging mother whose family forgets her at Christmas, a high school football star who suffers a concussion, then loses his grasp on his world, and a baseball game that takes a dangerous turn when one father’s need to win gets the better of him. “Tim had organized a workshop for Little League parents, trying to get them to focus on fun rather than competition,” says the narrator. “But it takes more than a two-hour seminar to change people’s attitudes about something as basic as the difference between winning and losing.” It is a world of grim realities, where happiness and youth are fleeting at best. In the title story, a teacher pries apart a slow-dancing couple, only to confront how he let the love of his life slip away. Nine inches may be close, but it is never close enough.

Mushroom Hunters by Langdon Cook.

Chronicling the fungus foragers who count posh New York restaurants as their clients.

In this non-fiction account, Langdon Cook tags along with mushroom foragers who scour the foggy Pacific Northwest in search of fungal gold. Along the way, this wild food expert uncovers a hidden society. Like storm chasers, Alaskan crabbers, and catfish noodlers, foragers come with their own sets of customs and rules. They move with the seasons, live outside the law, and count the best New York City restaurants among their clients. Following Cook through a slew of western states we run into scrappy businessmen, Laotian immigrants, desperate meth heads, and the shadowy treasures they hunt. “If the Hedgehog is the underdog of wild mushrooms, the matsutake an exotic foreigner, and the king bolete royalty,” Cook writes, “the chanterelle is a preening starlet on the red carpet, hoping—praying—for one more People cover.” That most of these mushrooms are “harvested” from federal land presents an interesting point of conflict: are foragers pirates or entrepreneurs in the spirit of Robin Hood? Cook eludes to his answer, but never quite goes there. Instead, his mission is anthropological. As his curiosity wanders, The Mushroom Hunters turns into a patchwork of profiles, anecdotes, factual information, and recipes that stretches thin at 270 pages. Cook, a forager himself, spent thousands of hours with his subjects, and the text betrays his attachment to them. As the title suggests, it is a story about the hunters, not about the hunt.

Mother, Mother by Koren Zailckas.

A manipulative, mentally ill mother inflicts cruelty on her two children.

In her bestselling 2003 memoir Smashed, Koren Zailckas tells the story of an unlikely alcoholic: her former teenage self. Now, her first novel tells the story of an unlikely mother. Josephine Hurst, whose character was inspired by members of Zailckas’s family, seems to have it all. In fact, she has narcissistic personality disorder, and we learn of the cruelty she inflicts on her family through the eyes of two of her children. Violet is the rebel, William is the lackey, and as their perspectives alternate, a portrait begins to emerge: Josephine is manipulative, amoral, and mentally ill. (Is this kind of mother really so unlikely?) This structure might have worked were it not for the fact that Violet and William’s voices are virtually indistinguishable from each other. As a result, the headings that appear at the top of each section to indicate who is speaking are more like a series of bandages, patching together a plot that doesn’t quite hold on its own. Mother, Mother quickly loses steam. In the acknowledgments, Zaicklas confesses a tendency to plant too many clues, and she thanks her editor for slashing them. But they missed the most obvious one. If Josephine is an uncommon mother, she’s also the likeliest villain. There’s not much thrill in a thriller if you can see the twists before they happen.