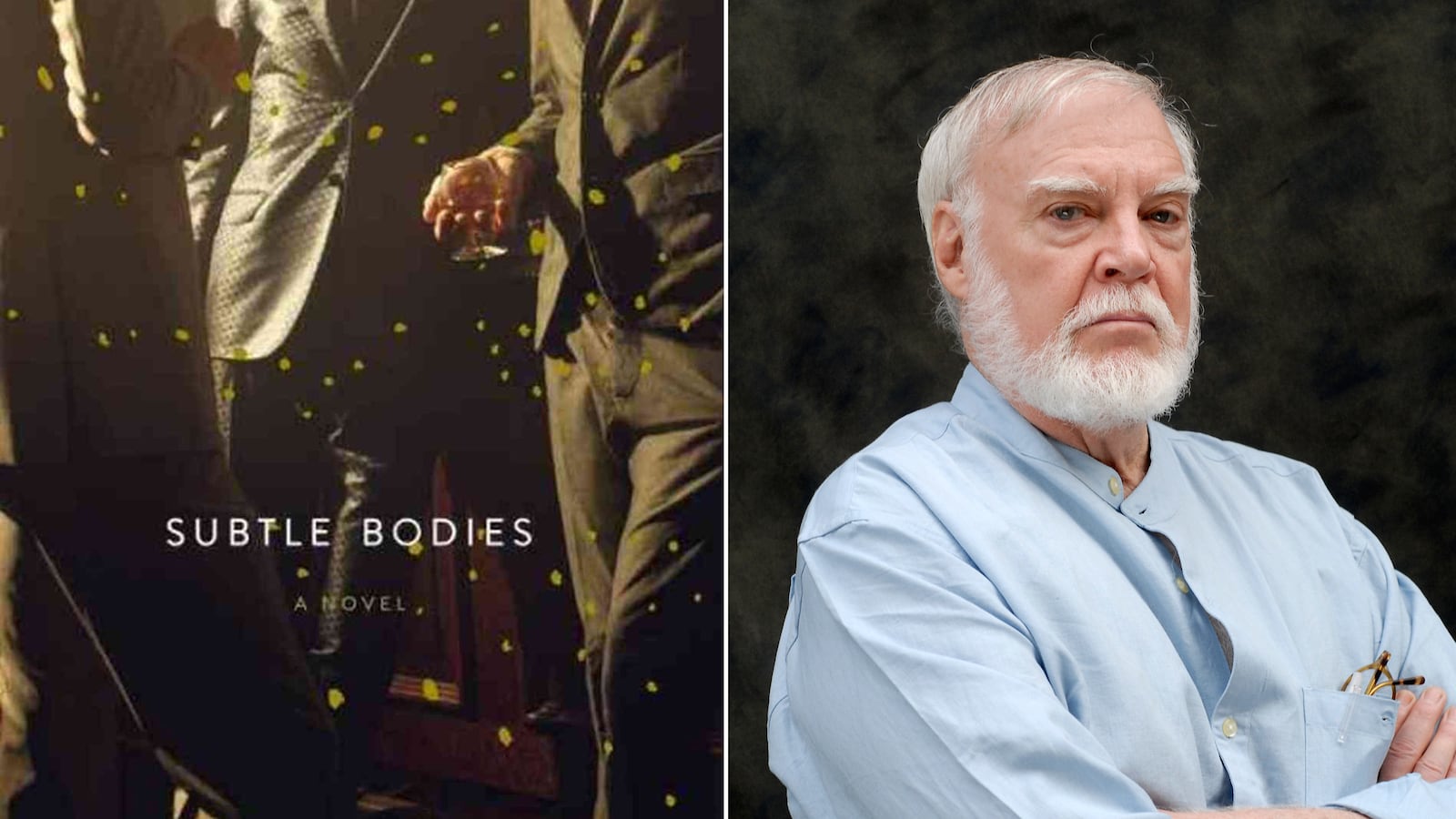

Norman Rush and his wife, Elsa, were co-directors of the Peace Corps in Botswana from 1978 to 1983. He has said he brought back to America cartons of material from which he and Elsa (I’ll explain shortly) produced three books of fiction set in Africa: a collection of stories entitled Whites; the novel Mating, which won the National Book Award in 199l; and in 2003 the novel Mortals, which received many admiring reviews. Each novel is longer and more ambitious in its cultural range and literary risks than the book before. Though essentially serious, the novels are also progressively funnier. Mating lightly satirizes Americans in Africa: the male founder of a utopian community in the Kalahari Desert and the female narrator who wants him as her husband. Mortals pretends to be an espionage novel to make fun of the genre, a too-literary CIA protagonist/narrator, and the confusions of religion and politics in a country that happens to be Botswana.

Those cartons must be empty now because Subtle Bodies is set close to home, particularly the Rushes’ home in Rockland County, New York, and employs the homebody Elsa more thoroughly than ever. In his Paris Review interview, Norman gives Elsa, whom he met in college, unprecedented and fond credit as a sounding board, argumentative partner, and constant editor. Elsa even participates in the interview and has some of its best, most pointed lines. (Full disclosure: I once hosted the Rushes at the university where I taught, and they were definitely a tag team, with Elsa jumping in whenever Norman was reticent.) The voluble Elsa is clearly the model in Subtle Bodies for the outspoken and witty personality, if not the circumstances, of the novel’s Nina, a 37-year-old woman desperate to become pregnant because her 48-year-old husband, Ned, would really prefer adoption. After he abruptly leaves their home in California for the funeral in New York of a friend from college, the ovulating and frantic Nina follows him to the deceased friend’s Catskills estate where three of Ned’s college classmates have gathered to mourn Douglas, the leader of their old NYU coterie, and, they discover, to participate in a television documentary about him intended to bail his widow and a teenage son out of debt.

Subtle Bodies may remind readers of The Big Chill but it doesn’t need a sound track. The novel has Nina. As Ned says, she is a “force of nature” and “born to comment,” so Rush wisely alternates point of view between her and Ned; “wisely” because he and his male friends are mooning about and mourning not just Douglas but also their own failing bodies and past-track minds while the busybody Nina is full of vitality and the future, for she believes that the conception she flew across the country to achieve was successful. Near the novel’s end, Ned tells Nina, “You will have to talk to yourself for a while,” but her silence doesn’t deprive the reader because her internal dialogue keeps on producing insights about the men, Douglas’s widow, Iva, and their wild child, Hume. Although Nina is not as educated as the men, has an astrologer mother whom she sometimes quotes, and is capable of goofy stunts like hiding in a closet to eavesdrop on the men, she charms Ned’s friends and commandeers the novel. Rarely does one get from a male novelist a female character as lovingly—but unsentimentally—portrayed as Nina.

Ned is an old lefty now working with California co-ops and organizing a San Francisco march against the imminent invasion of Iraq. He uses the memorial occasion to pester his friends to sign a petition against the war, and Rush uses Ned to bring out the political quietism or cynicism or worse of his 40-something friends. The rich stockbroker Elliot, who has organized the gathering, is too busy trying to replace Douglas as alpha male to discuss Iraq, though he takes plenty of time to describe his prostate operation. Gruen, who makes public-service announcements for television, believes the government will do whatever it wants. Maritime lawyer Joris would rather recount his wonderful nights in a high-end Manhattan brothel than talk about politics but ultimately rants against Muslims, stopping just short of Conrad’s Kurz: “Exterminate all the brutes.”

When in college, the gang of five thought of themselves as “molecular Socialists,” cultural provocateurs, and lit wits. Rush gives the survivors a positive quality or two, but now, except for Ned, they are basically opportunists, narcissists, or nitwits. Although Ned senses his friends’ intellectual and ethical decline, it takes Nina the accountant to pierce his nostalgia for the late ’70s in Greenwich Village and to reveal painful secrets kept from him by all four “friends.” By novel’s end, the once-obtuse Ned calls himself a sentimental “fuckwit” and wonders why he is giving his time to “meaningless personal history when the country was getting ready to burn people to death in large numbers.”

A reunion plot runs on secrets, and we know they exist from Elliot’s hushed arguments with Iva and from that sensitive instrument Nina, who should be working for NSA. We wonder what the revelations will be. We also wonder: does Nina really have a subtle pre-body in her body? Will Ned get those signatures and manage that march? Will the teenage Hume do something more outrageous than peep in Nina’s window while she has her legs above her head, trying to get Ned’s sperm to run downhill? Will the disgruntled Ned, Joris, and Gruen agree to follow their scripts in the bogus filmed memorial? Despite these modest plot points, Subtle Bodies holds the reader with the pleasures of its page-to-page observations, humor, and word play. At the novel’s beginning, Douglas dies in an absurd mowing accident, and the rest of the book is a mortality-tainted tour de farce, a bit like a French farce with characters changing rooms and engaging in revolving-door conversations that are both antic and sad. Subtle Bodies is black humor with a female face.

Ned thinks of his friends’ “true interior selves” as their “subtle bodies” and tries to discern if they “were still there and functioning despite what age and accident and force of circumstance may have done to hurt them.” Rush pushes his title beyond Ned’s notion of “authenticity” to explore another meaning of “bodies”—as “groups,” friends in a tight circle or citizens of a big country. In that Paris Review interview Rush recounts an experience with the poet Kenneth Rexroth that is the kernel of the novel’s social theme. A fan and friend of Rexroth before he enjoyed some fame, Rush found himself abandoned when Rexroth became known. The least financially successful member of the five buddies, Ned sees himself in a similar situation, marginalized by his richer East Coast classmates. Ironically, the revered but bankrupt Douglas would now be the least successful were he not dead.

Subtle Bodies perceptively dramatizes how class and politics and presumed erotic success create shifting male hierarchies that Rush parallels with the hierarchy of beauty for women. Douglas’s onetime lover, Claire, who later became Ned’s lover, was exceptionally beautiful, as is Iva. Nina, thankfully flawed, is not exempt from female jealousy and resentment. Nor is the ravishing Iva, who, when introduced to Nina, says, “I want your hair.” To Nina’s credit, her response doesn’t catch Iva’s follicle envy: “Nina felt a moment of involuntary alarm. For a stupid instant, Nina had believed her hair was being requested as a hostess gift.” Nina is “goodlooking” but not a show-stopper, and she knows where her body places her in the minds of the novel’s males who, in another irony, have the stereotypical woman’s concern with their physical appearance and clothes.

From this country house of fools, the reader can extrapolate out to the country at large, a move not necessary in Rush’s African novels because economics, race, politics, religion, and gender were sources of explicit conflict and cultural awareness. I worry that Rush may be too subtle in this all-American work, too confident an amused reader will recognize the estate as a microcosm of upper-middle-class social maneuvering and politics. Subtle Bodies wants to make American readers pause, as the characters pause after Douglas’s death, and consider if their now absent leader who took the country into Iraq was a clown and crank as Douglas was. Like Ned’s petition and protest march, the novel arrives too late to prevent the invasion, but Rush implies we shouldn’t forget those individuals and august bodies who let or made it happen. Also not to forget the massed bodies in the novel’s final section who tried to stop it.

Subtle Bodies moves quickly. It takes place over a few days and has 53 numbered sections in its 250 pages. An admitted devotee and two-time practitioner of the long novel, Rush has said he’d like to release his books in two versions, the Regular and Jumbo. A Jumbo edition might not have needed the style Rush has Ned call “choppy” because it would have plenty of space for Ned and Nina to complete their thoughts and finish sentences. This Regular version sometimes sounds like the near sequiturs of Gertrude Stein or her clever admirer Donald Barthelme. Were Subtle Bodies a first novel by Rush Norman, I’d probably have no desire for the Jumbo. For me, though, Norman Rush set a very high standard for himself with the 500-page Mating, its combination of African experience and anthropological research, of male sociopolitical discourse and female academic talk, of serious world building and comic deconstructing. But of course I’m not Rush’s ideal reader. Nabokov said he wrote for his wife and son. This time, I suspect, Rush is writing for Elsa. Subtle Bodies is a worthy gift.