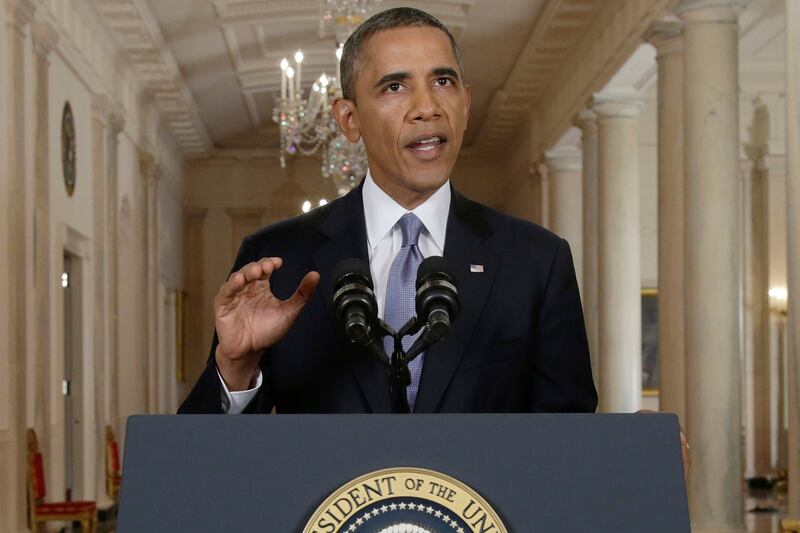

This was the best speech Barack Obama has given in a couple of years. (Read the entire text here. It was well-structured, right to the point, and direct; it anticipated the skeptical viewer’s questions and tried to answer them, and it did so persuasively. In places, it even did so powerfully, especially toward the end, where he made specific appeals to his “friends” on the right and the left to try to see this conflict in contexts that traditionally mattered to each side—the “commitment to America’s military might” to the right, and “belief in freedom and dignity for all people” to the left. And the sections of the speech that sought to tug at the heartstrings weren’t overwrought. He did nearly as well as he could have done.

This does not mean I think many people are going to agree with me, or more importantly, change their minds. Obama presented evidence and rational arguments to support his position. But when people have basically made up their minds, they don’t want to listen to evidence and reason. And most people don’t understand the region anyway. (It might have been helpful if they’d cut away to a map.)

The speech had four clear and logical sections. First he talked about the unique evil of chemical weapons—what they do to civilians, especially children, and then, a brief but strong bit on their history and why they are the target of distinctive opprobrium. Second, he tried to make the case that all this is directly threatening to U.S. national security interests. “If we fail to act,” he said, Assad will act again; and if Assad acts again and goes unpunished, other dictators might follow suit. The third section was the most important, in which he addressed the five or six key questions on the minds of the war-weary public. And finally, he closed it out with a historical argument: “My fellow Americans, for nearly seven decades, the United States has been the anchor of global security. This has meant doing more than forging international agreements; it has meant enforcing them.”

It was within the third section that he discussed the late developments relating to Russia—just a couple of sentences, noting Russia’s new role and Syria’s announced willingness to join Putin’s proposed chemical weapons ban. This was one place where he could have gone into just a little more detail. I would guess Americans were hungry to hear more here about how this would work. But it’s probably just not worked out yet. There are many, of course, who believe that it isn’t going to be worked out. On the right, there emerged on Tuesday a universally mocking view that Russia is playing Obama like a cheap violin. Others who aren’t cackling, like NBC’s Andrea Mitchell, who has diplomatic sources around the world like few other journalists, are still doubtful that Putin is really going to play ball here.

This makes what Obama and John Kerry manage to wring out of the Russians in the next two days absolutely crucial. The United States insists that the option of force—a sword of Damocles—be included in any Security Council resolution. Russia insists that it not be. There wouldn’t seem to be middle ground there. Someone is going to win that argument, and someone is going to lose it. The way for the Obama administration to win it is to give in on other points. One question might be whether they give so much that any monitoring of Assad’s weapon stocks ends up being in essence unenforceable.

We’ll know a lot more by the weekend. In the meantime, Obama is presumably more than happy to put off a vote in Congress, because it was increasingly looking like he was going to lose there. Right now, his best course is to try to cut that deal with the Russians and then hope legislators are surprised and impressed enough by the fact that he’s done it that they’ll give him a yes vote.

But the public opposition to military action in Syria is not going to change dramatically. That’s the cold, hard fact. If Obama can get a deal that contains most of Syria’s illegal weapons, great. Even it wouldn’t give him much of a boost in the polls, at least he’d have won, politically. And if Russia walks away, and he has to go back to Congress, he’s back where he was, although in worse shape because he’ll have been rebuffed (or, as the neocons will have it, humiliated) by Putin.

To me, it’s a shame. Assad is a madman, and the United States doing nothing strengthens the worst actors in the region, many of the worst actors in the world. But the American public was told before about a “just cause,” and it was a lie that time, and they just don’t want to hear it again, and in a way you can’t blame them. But if you have a humanist bone in your body, take a moment, please, to think of the people of the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian National Council—the moderate rebels. By and large, they want the United States to strike. We could strengthen them against both Assad and the extremist rebels. But the right hates Obama, and the left hates militarism. Nothing Obama said Tuesday night altered those postures. Still, over the next few days, he has the chance to turn what was a certain political defeat into a draw or maybe even a win.