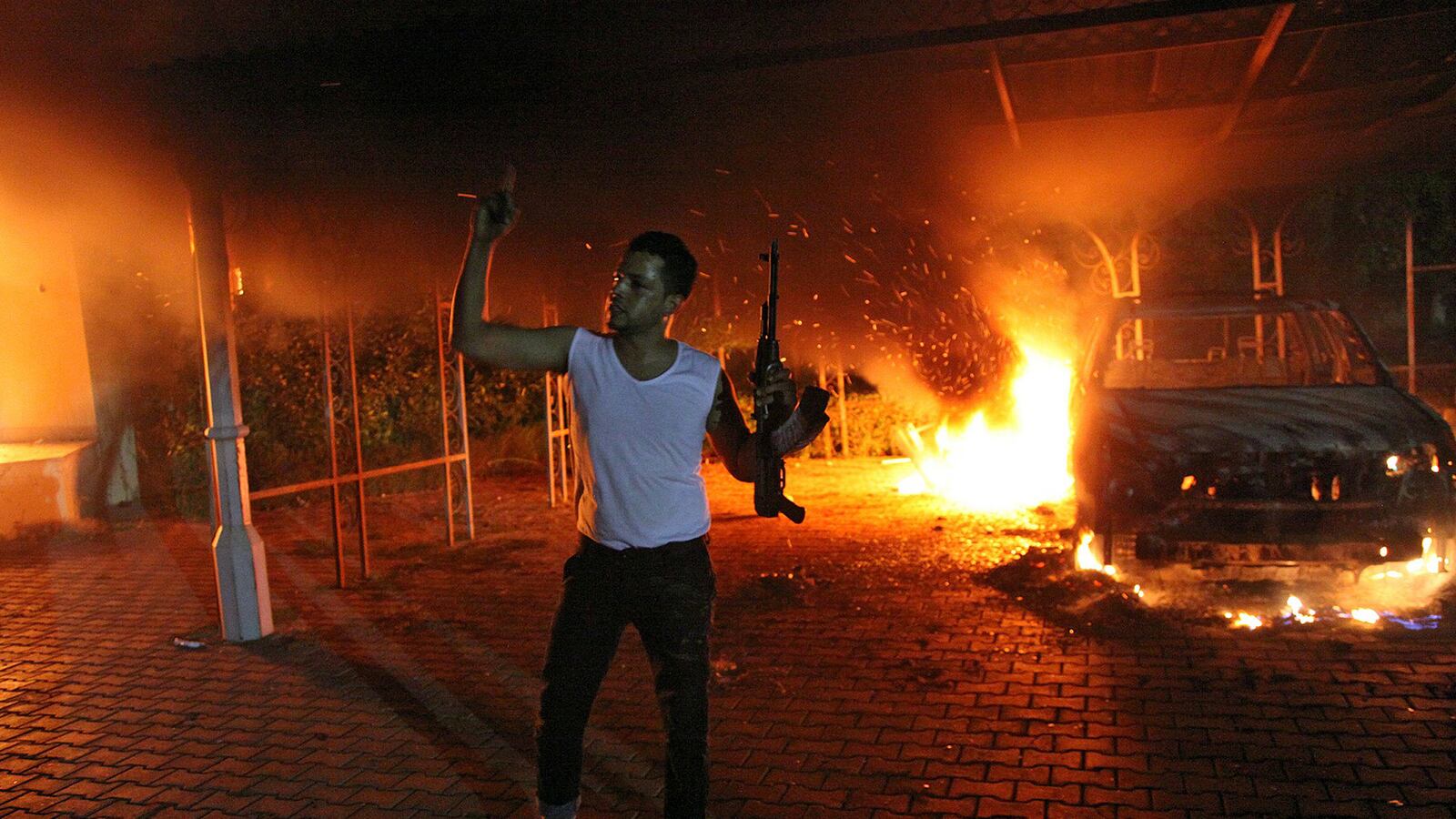

A year after radical Islamists attacked the U.S. mission in Benghazi in an assault that claimed the lives of U.S. Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans, the suspects remain at large in eastern Libya—to the mounting frustration of American officials working to bring the assailants to justice.

Benghazi isn’t exactly a city that FBI agents have been able to spend much time in, so much of the evidence has is based on U.S. drone surveillance and on electronic intelligence.

Several of the ringleaders have been indicted in absentia in a New York court, and U.S. officials say evidence of their involvement in the attack has been shared with Libyan authorities. But so far, the Libyans have made no moves to apprehend the indicted suspects—an inaction that has some American lawmakers, including Michigan Republican Mike Rogers, chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, fuming about the lack of consequences for the taking of American lives.

Rogers suggested this week that some sort of military action should be mounted to seize the suspected ringleaders, who include Ahmed Khattala, the 41-year-old founder of a Salafist militia called Abu Obaida Bin Jarrah, which has some crossover membership with Ansar al-Sharia, an Islamist brigade first identified by eyewitnesses as having some of their members participating in the assault last September 11.

The Libyans don’t have the excuse of not knowing Khattala’s whereabouts—he is not a hard man to find. He has been interviewed in Benghazi by several Western media outlets, and last January would-be assassins placed a bomb under his car that detonated prematurely, killing one of the bombers and injuring another, say Benghazi police. That assassination attempt had nothing to do with Stevens’s death, say Libyan security sources: the bombers were seeking to avenge a relative’s death in a separate incident.

Khattala has admitted he was at the consulate as it came under attack by a heavily armed group of gunmen but has repeatedly insisted he was not a ringleader and didn’t participate in the fighting. But he has never renounced the attack and has openly stated his disapproval of democracy. He says he’s sympathetic with al Qaeda’s aims, although not a member of the terrorist group.

Some U.S. officials and lawmakers assign dark reasons for the failure of the Libyans to question Abu Khattala and interrogate other suspected ringleaders, let alone seize them, but the truth is more prosaic—the central Libyan authorities just don’t have the firepower to take on the militias involved and no inclination to confront them.

“The authorities can’t do anything—they don’t have the force to be able to make arrests,” says a European diplomat based in Tripoli.

In the year since heavily armed assailants attacked the U.S. consulate, Libya has gone from disturbingly wild to downright unruly, and the central authorities have grown weaker.

Benghazi has been engulfed in violence with waves of score-settling assassinations and the authorities struggling to contain the chaos. Lawlessness has increased elsewhere, too, with militia-on-militia clashes being seen once again in the capital of Tripoli and drug-smuggling, armed robbery, and car jacking on the rise.

On August 19, a group of gunmen attacked a convoy carrying the EU ambassador to Libya, Nataliya Apostolova. The assault outside the Corinthia Hotel in central Tripoli was not far from Prime Minister Ali Zidan’s main office. The gunmen robbed the EU delegation at gunpoint before shooting at passing cars and making their escape. Policemen outside the hotel did not dare intervene, according to EU diplomats.

Privately, Libyan officials conceded long ago that their own probe into the events of that night was hamstrung not only by the absence of experienced investigators and a functioning police, but also by the central government’s lack of authority in Benghazi—and increasingly elsewhere in a country where revolutionary militias, some Islamist, others not, exert the real power and the government day by day appears diminished.

The story of the night America lost its first ambassador since 1979 to violence remains a jigsaw puzzle—the pieces have been fitted together slowly by the U.S. intelligence community but a complete picture remains elusive, partly thanks to the lack of assistance from the Libyans, say U.S. intelligence sources.

Reliable information from the Libyans has been in short supply from the start and in the hours after the attack it was the Libyans who first insisted the attack was a demonstration gone wrong, an opportunistic assault by a flash mob triggered by an overreaction by the mission’s guards.

That explanation was maintained days after the assault by advisers to Mustafa Abushugar, who was elected Libya’s prime minister 24 hours after the attack, who told The Daily Beast in the week of the attack: “So far we really believe that this was a violent demonstration mainly against the movie (The Innocence of Muslims) that swung out of control. The protesters saw on television what was happening in Egypt and decided to have their own protest. We have no evidence at all that this was al Qaeda.”

But evidence quickly mounted that this was an orchestrated and directed attack planned well and efficiently executed with road blocks set up to hinder rescuers and great precision and accuracy demonstrated by those firing mortars at the nearby CIA annex where the Americans from the mission fled under withering automatic fire.

According to Rami El Obeidi, who headed intelligence for Libya’s National Transitional Council during the rebellion against Colonel Gaddafi, al Qaeda didn’t order or plot directly the assault on the U.S. Consulate but encouraged the attack, and the decision to do so was taken not by a single mastermind but by a committee of Libyan and Egyptian jihadist ringleaders. “Radical cells in several of Benghazi’s revolutionary militias were involved in the decision,” he says, including members of the February 17 Brigade, the militia that also had guards detailed to protect the consulate the night of the attack.

He says the leaders of the militia most frequently blamed for the attack, Ansar al-Sharia, were not involved in the assault, although radical subordinates were. Others involved came from the Omar Mukhtar brigade, the Abu Salem Martyrs Brigade, and the Rafala Sahati brigade. Three Algerian al Qaeda members were present during the assault on the consulate. It is a claim a current Libyan intelligence source confirms.

Most U.S. intelligence sources agree with El Obeidi that this wasn’t an attack mounted by core al Qaeda but by radical Islamists, some of whom have links with al Qaeda or share the goals of the terrorist organization. But without some of the ringleaders in U.S. hands, much of the full story will remain unknown.

There is scant chance this will happen soon. The government’s problems go well beyond street crime and lawlessness though. Political leaders in the east of the country have been agitating for less centralized governing structure since the overthrow of Gaddafi, and now once again are threatening to break away from Tripoli.

Since July, Zidan has been struggling to overcome a strike by oil industry guards that has shuttered export terminals and resulted in oil exports plunging by 70 percent, a devastating setback for Libya, which relies on oil exports for nearly all of its foreign revenue.

“What we are seeing are shifting coalitions involving militias and different political groupings jostling as much over short-term economic interests as anything to do with political ideology,” says a political risk analyst who advises international oil companies.

To complete the dismal picture, in the last few months al Qaeda has established a significant foothold in the country, according to former and current Libyan intelligence officers, with half a dozen training camps being established for jihadists forced out of Mali by the French intervention there. That intervention was punished by a bombing of the French embassy in Tripoli in the spring, a worrying sign of a reconfiguration of jihadist ranks in a Libya ill equipped to cope with further security challenges.