“Being trapped by genre is pathetic,” says Edmund de Waal. Given what he’s done, it’s hard to take issue.

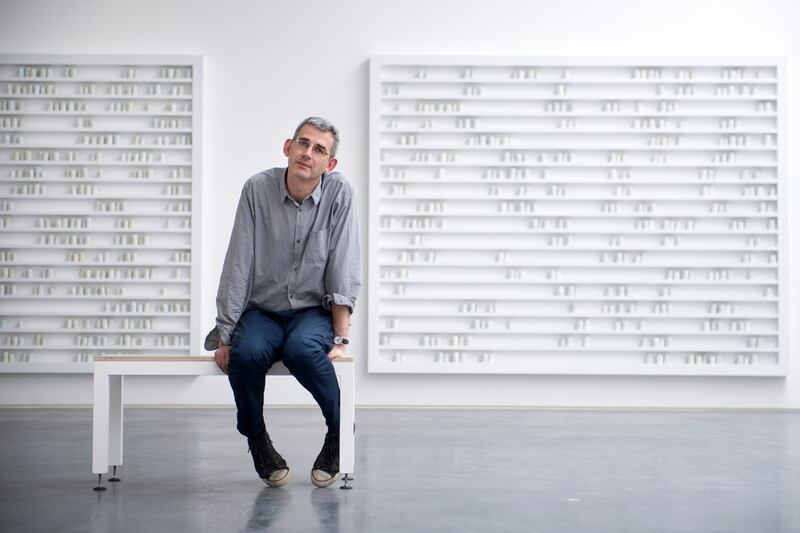

His book The Hare with the Amber Eyes, a record of the travels of a collection of tiny Japanese Netsuke carvings in the hands of family members, enduring fortune and folly across Europe and Japan over three centuries, sold by the truckload and won a shelf of awards. By then he had confirmed his position as one of the leading ceramic artists of his generation, exhibiting at the best museums and selling to the pickiest collectors. His art has brought him to New York, where he’s been signed up by Larry Gagosian for his first US show at the gallery on Madison Avenue.

He’s been making pots since he was five and now he’s 48 or thereabouts. For a long time these have been mostly white or very nearly so, simple in form and mostly arranged in multiples displayed in cabinets and vitrines, often juxtaposed with other objects in unconventional settings, the roof of a museum gallery, say, or in the elaborately decorated rooms of a country house. And he’s even working on a new book about the color white.

On a blisteringly hot day in mid-summer, in his cool, nearly all-white studio next to a bus depot in the dusty, unlovely south-London neighborhood of West Norwood, he explained why his pottery and his writing are part of the same process, why art fairs aren’t good for his skin and pondered what it might be like to be in the movies.

Looking at the space around us, there’s an air of calm and solitude and monkishness and Zen, but in recent years you’ve been right in the spotlight. Are you comfortable with that?

No. But I’m grown up enough to know that I have to deal with it. When Isaac Bashevis Singer won the Nobel Prize he was doorstepped the next day in this little Yiddish cafe where he always drank and he was asked: “Mr Singer, are you surprised?” And he said: “How long can a man be surprised?” I’d much prefer to be quieter because you can’t actually work with intensity with a lot of noise and interruption. You can’t look carefully, you can’t think carefully, you can’t write carefully. But the last few years have also brought a lot of extraordinary things, so I’m not unhappy.

There are compensations…

There are massive compensations. Nothing happened very fast for me. It might feel overnight for some people but actually I’ve been doing this for 40 years so it’s not like I haven’t been thinking what I would like to do with my work. The tiring things aren’t really around making. The tiring things are around the afterlife of the book [“The Hare with the Amber Eyes”] which are the demands to endlessly return to that territory, to go through again the story of how it happened. And also to talk about some of the really tricky, complicated stuff to do with politics and restitution, which I’m prepared to do but it’s emotionally quite taxing.

Because it’s so personal?

Yes. This is the 75th anniversary of the Anschluss. And I’ve had to go back to Vienna to do things there. And of course I’m not going to say no. But that has a cost. Making’s great though.

Do you see your work as part of a particular genre? It’s craft-rooted, yet you make pieces with very contemporary titles, for example “Self portrait in a concave mirror”. You’re about to show at a leading contemporary gallery and yet you also dislike the term installation…

Being trapped by genre is pathetic. You have to call your own shots. When I was writing the book I was in flight, serially, from family memoir, fin de siecle reminiscence, cultural history, art history, a history of migration… all these things were generic traps which homogenized what is a tricky way of looking at the world. I make objects out of porcelain, which are vessels. And I put them in different kinds of cabinets and vitrines and then put those into different spaces. So what is it? It’s patently sculpture of a kind, it talks to architecture I hope, it’s very much rooted in poetry and music, it’s pottery at a very real level. But it doesn’t slip effortlessly into a contemporary genre.

But people try to categorize you?

Yeah. All the time. Which fucks me off. Everything is claimed by contemporary art - that’s fine, I have no problem with that. It can be performance or installation, it can be dance. It can be film, it can be a happening, it can be an idea, it can be a prescription. All these things are fine. But it’s interesting how tricky people find it when you make something out of clay, which is suddenly much more worrying for some people. Some people want to pull it back towards utility and function, when it’s nowhere [near] there… it’s so abstracted from that. It’s got much more kinship with music, I think, in the sense that you can hear the spaces between things and the different volumes within each object.

You’ve talked about music and serialism a lot. Is it a synesthetic connection?

Yes it is. It’s interesting talking with composers and with musicians. They often get it quite easily. It’s sometimes more of a stretch when people come from a purely visual arts background. And writers seem to get it a lot, the relationship between words and page and phrase and paragraph, or stanza.

As both a writer and a maker of objects, both practices must be psychologically very close for you.

They are very, very close, completely. Writing and making - and the process of editing as well, coming back to something and taking away, those kind of iterative comings and goings feel kind of the same. And in fact this big show here, the show that’s going to New York, is actually a conversation with Paul Celan, this wonderful poet who wrote in German, so it’s a whole long conversation with him.

Were you surprised to be approached by Gagosian?

I’ve been showing in very good galleries for a while and in museums a lot over the last 15 years and at Art Basel and other fairs. I’m not sure where [Larry Gagosian] saw what I was doing.

Is this a US only arrangement?

It begins with the New York show.

Does this mean you’ve switched representation in the US?

I didn’t have any.

Can you remember the first time you had anything exhibited? At school, later?

I had an exhibition in my second year at Cambridge. In a room in my college.

Did you get to a stage where you thought “I really understand why I’m doing this now, it’s a good job I lucked on asking my dad to do this”? [De Waal has written that when he was five, he asked his father to take him to a pottery class.]

I can absolutely remember as a kid the intense interest in the idea of making a space. It wasn’t about what it looked like from the outside at all. It was that this idea of making an inner space seemed to me so extraordinary. And 44 years down the line I still get that… I still get that very strange, bodily, somatic thing. It’s very odd to make a volume in the world, to make a space, to define something. It’s like capturing a bit of the world that isn’t really there. It feels temporary, a brief holding.

You quoted someone who said that the first 30,000 pieces were the hardest. How’s the technique now? Do you feel completely in control or do you think “I’ve still got everything to learn”?

I genuinely feel I haven’t started. I would pray for a long life, to begin to be able to sort things out. I’m really excited by what I’ve just made and by what I’m just about to start making, which is a tremendous place to be. Next year I'm doing a project with Turner Contemporary at Margate [an English seaside town] where we’re going to make some vitrines that hang in space against the sea so you see things against the horizon.

Outside or inside?

Inside. So it’s being below objects, so you can feel their presence. I’m also making a vitrine in the ground which you can walk across.

The stuff here, the Gagosian show, the big, big, huge quartet... there’s a whole space I’m going to make where I hope you’ll be winded by the feeling of infinity, of mass. So I haven’t really started, I’m just getting going. There are lots of exciting things that have to happen in West Norwood. Just next to the bus garage.

You didn’t go to art college, you did an apprenticeship while studying at school. Were you so focused on what you did that nothing else mattered?

I did identify what I was going to do pretty early on.

Was it difficult alongside studying?

No. For me learning to make and reading and writing are not polar things at all. I didn’t oscillate between them, they are very closely aligned.

I wanted to ask about the placement of your work. They’re interventions…

They are…

I was thinking of the ceramics gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London where works are up near the ceiling and you can barely see what is going on. And at Waddesdon Manor last year, items were placed in certain places, juxtaposed with objects that look entirely different. What is the intention?

There are a couple of answers. One is that I’m interested by how little you can do in a space to alter your experience of it. So at the V&A or at Kettle’s Yard [in Cambridge] things were very hidden. I did a show where one really pissed-off reviewer couldn’t find the work, which really pleased me. Doing one simple thing is like a conversation or commentary on a place or a collection, which is really dynamic. I really hate those 1990s interventions where you just tripped over stuff, which was like an ego-trip. Like “look at me look at me”, which weren’t really about the identity of the place. But Waddesdon is a house which is completely about collecting, completely about Jewish identity [it was home to the English branch of the Rothschild family], completely about émigré life. So how the hell do you work with a Belle Époque, over-the-top, over-gilded house full of French porcelain and furniture? So there, in some ways, the vitrines were actually protecting the work from their environment as well. They were containing the work, and letting it be. I made these new vitrines, thick, Perspex spaces where things floated above all this furniture so they could be present and have a slightly ironic distance.

Now I’m working with other collections. I’m going to be doing something with the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna next year where I choose favorite things from the collection. It’s going to be a complete joy trying to find a way of working in such a powerful institution. Bring it on!

There was a line that really jumped out at me in The Hare With the Amber Eyes. You were looking at your ancestor Charles Ephrussi’s bed and you wrote: “Connoisseur, goes the alarm.” What were you wary of at that point and is that something that you’ve moved on from? Is it unfair to pull that out?

I wrote the damned thing…

People change…

There’s always an anxiety about preciousness, of serial over-parenting. That kind of slightly over-anxious, wrapping up of objects in connoisseurship brings me out in hives. It really does. Just like I hope people who live with my work don’t cosset it.

Are you at that stage in your career where your gallery will ring up and say “so and so’s in town for a few days, I must bring them down to your studio” and you have to go through that whole rigmarole?

People do come to the studio and that’s often a really good experience. I don’t mind people coming and talking to me about what I’m doing.

I was wondering what would bring you out in hives again.

When I discovered that I don’t agree with art fairs, that an artist going to art fairs make me ill…

You’re a refusnik?

The brutality and the commodification of what you’ve just done is just too total for me. I’m English enough to enjoy that separation. I like making stuff, talking about how it’s going to be curated and then finding out later about whether someone’s bought it or not. That interim process of seeing it being sold is a bit of a shock.

I loved the title of the show at Alan Cristea in London last year, “A Thousand Hours”. I assumed that was how long it took you to make it…

One of the really interesting things in contemporary art is about the loss of time. The process is neutral, it’s not a good thing or a bad thing, but long looking and long making do something different from short looking and short making. And I just wanted to investigate what it is like to spend that amount of time.

Again you couldn’t see all the elements it contained…

No you couldn’t. Why should you have everything? Why should everything be present? And gettable. And Google-able? And handle-able? What I was trying to do was resist. In fact there’s quite a lot of resisting.

You’re asking people to put in quite a lot of work.

Yeah [emphatic]. And sometimes it’s made manifest through opacity, or through shadows or through darkness or being 75-feet up in the air in a dome or wherever. But not everything has to be given or gettable. It still pisses people off though.

Do you like that? That it pisses people off?

[Long pause] I enjoy a full range of responses. [Laughs]

“A Thousand Hours” is a very upfront and explicit title. Is there a consistency in the way you name things?

No, there’s a real inconsistency in how I name things. Phaidon are doing a monograph next year and it’s going to include two pages of titles. Sometimes [a title] is referential, sometimes it’s a stone chucked in the opposite direction to distract you. You make something out of porcelain, which is completely fragile and it’s inconsequential, it could break in a second. Then you arrange it, install it, in this way that you think is beautiful and poetic and has energy and you title it and send it out and you think “how the hell’s that going to survive out there?”. It’s a completely ridiculous thing to do. And the titling is part of that, of the craziness of this whole enterprise.

Are you approached about collaborations?

Yes, but the last couple of years have made it really tough to say yes to anything. But yes to choreography, yes to music.

You were writing another book - on the color white. Is it still happening?

It’s well underway. It’s at that stage where I’ve done a lot of research for it. I’ve been in China, I’ve been in Dresden and in Venice. And in Cornwall, up a hill. It’s a book that looks at what white does in the world. So in theory it’s about porcelain and in practice it’s about the presence of white from early China to Robert Ryman. And it’s a kind of autobiography.

And there’s going to be a film adaptation of The Hare with the Amber Eyes?

It’s being written.

As a piece of fiction?

I don’t know, I’m very hands off with this. There’s a fantastic person who’s writing the script. [De Waal asks me to turn off the recorder and mentions the name of a very high-profile playwright and screenwriter.]

Do you know when it will be out?

No idea. But I’m really interested to see who’s going to play me.

Was that on the record?

That’s fine. Who the hell’s going to play me?

You’ve talked about how the book has been received differently in different territories, restitution and Jewishness being big topics in the US, how the French have a bit of a problem with it per se, particularly the sections about Proust [De Waal wrote that Charles Ephrussi was a possible model for Proust’s Swann]. Do you get the same response to your work? Does it have different meanings in different territories?

Ask me again in five years time because I don’t really know. This particular exhibition is a huge moment. It’s going to bring together people who’ve read what I’ve written and haven’t seen what I’ve made and the people who know what I make but haven’t read. I have no idea what’s going to happen.

Things heading towards each other.

At speed… might not be good.

And now your grandmother’s book has been published as well [“The Exiles Return”, by Elizabeth de Waal]. Do you think that could have happened on its own or that you’ve enabled it?

No one would have known about it if I hadn’t mentioned it in a throw away line in “The Hare…”. It’s kind of a restitution… it’s coming out in Germany in the autumn, which is tremendous. She wrote these novels in the 1920s in German about the end of the Habsburg empire. And people are saying we want to read them from this lost writer. I feel very proud of her.

Do you think you’ll ever get to a stage where you give up working with porcelain?

[Long pause] Not in this lifetime.

Edmund de Waal’s exhibition “Atemwende” is at Gagosian, Madison Avenue, New York City, from September 12 to October 19.