NC: Describe your morning routine.

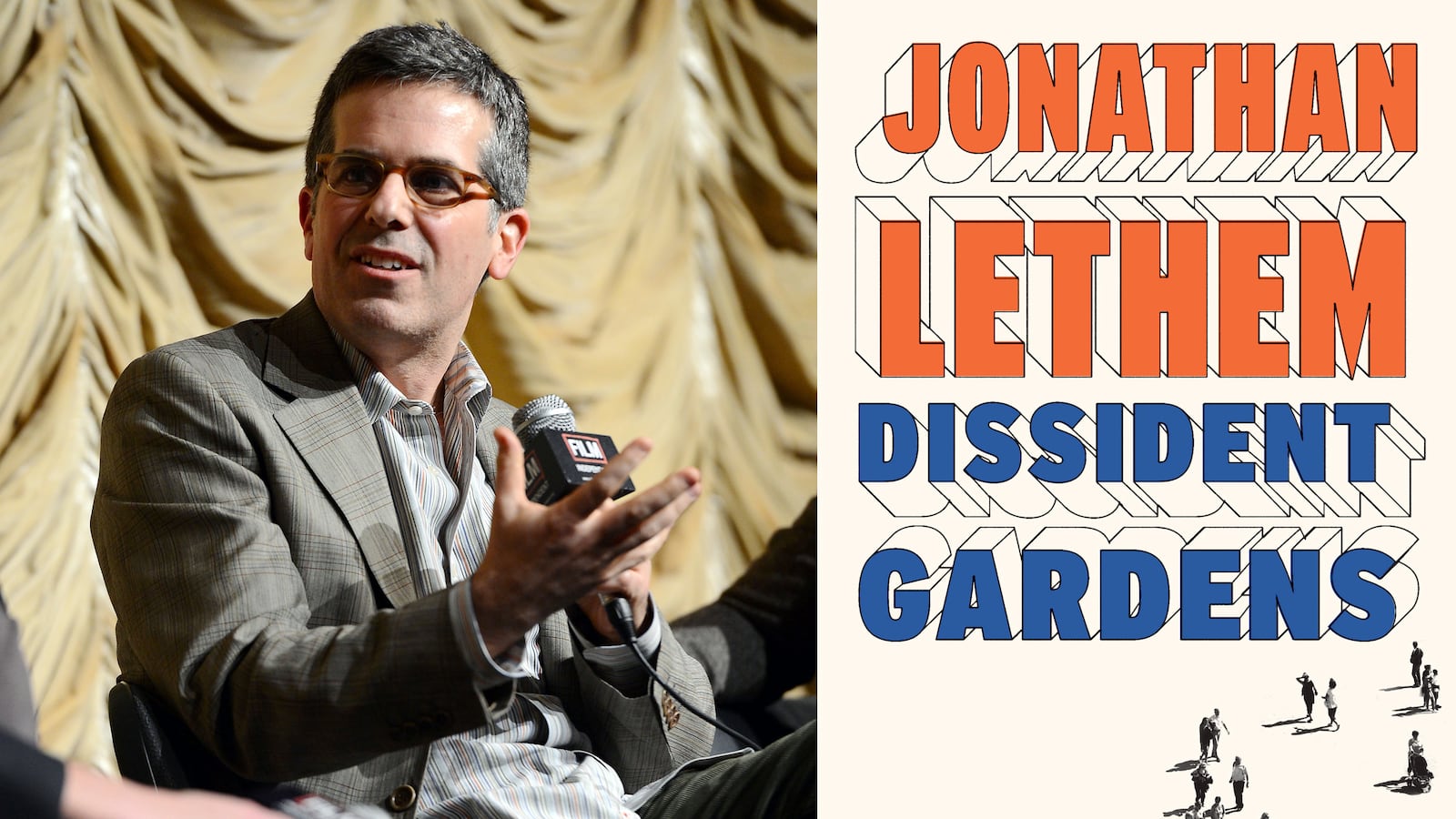

JL: OK, so my morning routine. Well, my life is totally dictated by the presence of these two wonderfully little boys. I have a 6-year-old and a 3-year-old. They are insane early risers, which forces me to trump them. When I was writing Dissident Gardens, which was the last really good roll I got on, when I was in the full grip of it and needed to work substantially on it every day, I’d get up at 3 or 4 in the morning. I’d make myself a cup of coffee from my Nespresso machine, sitting in the dark in the kitchen until the boys woke up. Then I’d make them breakfast, pack their lunches, and sometimes get back to work later on. But if I had two or three hours in the very early a.m., it didn’t matter. So my day was usually over before anyone else’s had begun.

Do you have any distinctive habits or affectations related to writing?

I probably do, but they’re so deep inside me that I don’t know. I listen to music, that’s one thing. That doesn’t surprise people, but it does when I tell them I also listen to baseball on the radio. If the Mets are playing, I’ll have the game on. I have a dual track, and I need to fill one of the tracks with something busy, some kind of chatter. I have a horror of total silence.

You are officially a genius, having received a 2005 MacArthur “genius” grant. That’s a pretty sweet thing to have on the résumé. What was the awards ceremony like?

Well, one of the things that makes their system remarkable, an aspect of their generosity, is that there’s no ceremony. They’re adamant that you have no obligation to them to parade around, to insert their title into your books, to wear their emblem on your T-shirt. They almost refuse to be thanked. They just tell you it’s coming, and you owe them nothing. They remain nearly as mysterious to the recipient as they are to the larger public, or anyway as they seemed to me, before I got it. The phone call telling me I’d won one came when I was in a car wash, under the brushes and bristles, so it was difficult to hear what they were saying. Then they covered my mortgage.

How did your career change post-fellowship?

It gave me time. It’s really hard to get off the treadmill and go on a really long journey. It takes luck, and opportunities are sacred. When Motherless Brooklyn won the National Book Critics Circle Award, I felt I could exhale, after working frenetically. Suddenly I had this opportunity to slow down, and I produced The Fortress of Solitude. In the most direct way, the MacArthur luck became “The Ecstasy of Influence”—just an essay, but one of the most demanding things I’ve ever done. And then it became Chronic City, a book I’m very proud of.

Tell me about your process when conceiving of a new book, but before writing begins.

I usually live with the idea of a book for years, before I actually know what I have. To use a chess word, I spend a lot of time visualizing endgames. It’s in my head, this elaborated sense of what I want to have happen. But I’m sort of allergic to notes, diagrams. I don’t really put anything on the page. So if I were to die in the middle of any of these operations, it’d be like The Mystery of Edwin Drood—you’d have no idea what was meant to come next.

Do you have a goal in writing each day? A word count you aim for?

My way of satisfying myself is really simple. I try not to count anything: words, pages, hours at the work site. They vary wildly over time, anyway. Sure, if I write three pages instead of half a page, I notice it, I’m pretty excited. But I work every day. If I do that, all the other counting, all the other considerations can melt away. I just make sure I make contact with the book every day. And it gets done.

Is there anything distinctive or unusual about your workspace? Besides the obvious, what do you keep on your desk? What is the view from your favorite work space?

Well, my primary workspace is kind of a closet. A walk-in closet. I guess I’ve worked at both extremes: big vistas and tiny burrows, like Kafka’s mole. So maybe it doesn’t matter to me, but I need the space to be eccentric and purposeful. I seem to thrive on either a great view or its opposite.

What do you like to snack on when you write?

I go for a lot of brain oil. Sardines or avocado on rice cakes.

You write short stories, novels, and essays. Does any one medium come more easily to you than others, and does your approach differ, depending on the medium?

I feel natively that I’m a novelist. I like the long marathon immersion. I like to feel that way, that I’m in the middle of a long thing, forever. I take pleasure in the other genres, and they have a simple advantage: you get to finish. You can experience the titillation of finishing something more than once every three to four years. They tend to be sprints, more spasmodic. When you glimpse the finish line of a project you’re enlivened, but I wouldn’t trade it for the slower satisfaction.

You worked for many years as a clerk in used bookstores. I found myself thinking of Quentin Tarantino’s background as a video-store clerk, prior to his writing and directing career, soaking up a private master class in classic films thanks to his mundane day job. What did you get, as a writer, out of your time working in used bookstores?

It meant a lot of things to me. I mean, to relate it to Tarantino, I knew there was a lot out there. I became a reader of the exiled books. In a used bookstore, you read the ones people don’t take away. I care tremendously for the nooks and crannies of the shelf, the dark horses. I write as much out of identifying with those books as I do with the frontline canonical stuff.

If a reader would like to try one of your books but is unfamiliar with your work, where would you recommend they begin?

They’re so crazily different, each of my books. If I had the chance, I’d interview the prospective reader, to ask what else they like. Then I’d choose the book of mine according to their tastes. I’ll say Motherless Brooklyn, because it’s the most grabbing, kinetic, warmest of my books. It’s probably the best one to start with.

Many of your books span genres (sci-fi plus detective fiction, for instance). When some authors try to do this, their publishers and publicists object, because they think it confuses audiences—that you’re supposed to pick one genre, develop a genre-specific readership, and stick to it. What are your experiences, from the practical publishing side, of your diversity of book types and cross-pollination of genres?

Yeah. I kind of preempted anyone having an opinion on this, because I was so aggressive on this at the start, before I knew anything about the practical publishing world, and before the practical publishing world had a say. I wore it on my sleeve that I’d be this guy who would jump around. It was either going to be a good thing, or not, but they’d be helpless to stop me.

How did Promiscuous Projects begin, in which you offer to license selected stories of yours to filmmakers, theatrical producers, and musicians, for just $1, and has it worked out as you hoped?

Oh, yeah, it’s been a gas. I just heard from another film director. She just shot a short version of “Sleepy People.” It seems like I offered a gift to others, but the reverse is true—I get these gifts coming back to me. I get this fabulous flow of filmmakers and musicians and theater people who come at me with these responses to my stories. What luck for me! You have to remember, it’s always luck that anyone cares about your work at all. So to have these exchanges, the reciprocity has been marvelous.

What is guaranteed to make you laugh?

My kids.

What is guaranteed to make you cry?

Sports victories.

Uh, you’re a Mets fan, aren’t you?

Uh, yes. That brings a different sort of tears.

Do you have any superstitions?

I probably do. They’re so integrated that I don’t feel superstitious. I suspect I’ve disguised my superstitions as rational behavior.

If you could bring back to life one deceased person, who would it be and why?

How do I explain this to all the other deceased persons that I’m neglecting? I’ll say my mother.

What phrase do you overuse?

Having a 3 year-old echoing you back to yourself means learning there are a hundred phrases you overuse. I say “actually” too much.

Was there a specific moment when you felt you had “made it” as an author?

The first hardcover book. For me it was that simple. I was on the shelves. I didn’t need a lot more.

Tell us a funny story related to a book tour or book event.

There was the time that Graham Joyce and I went to a chain store in the suburbs of Chicago, to sit together to sign books. We literally had one taker. He didn’t even have a book, just a piece of paper to sign. And it was torn. Not even a whole sheet. The ratio of authors to readers was 2 to 1, there were no books signed, and the paper we shared between us was torn!

What would you like carved onto your tombstone?

I’ll have to steal this from another friend of mine, John Kessel. He wants his tomb to read: “He didn’t know, but he had an inkling.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.