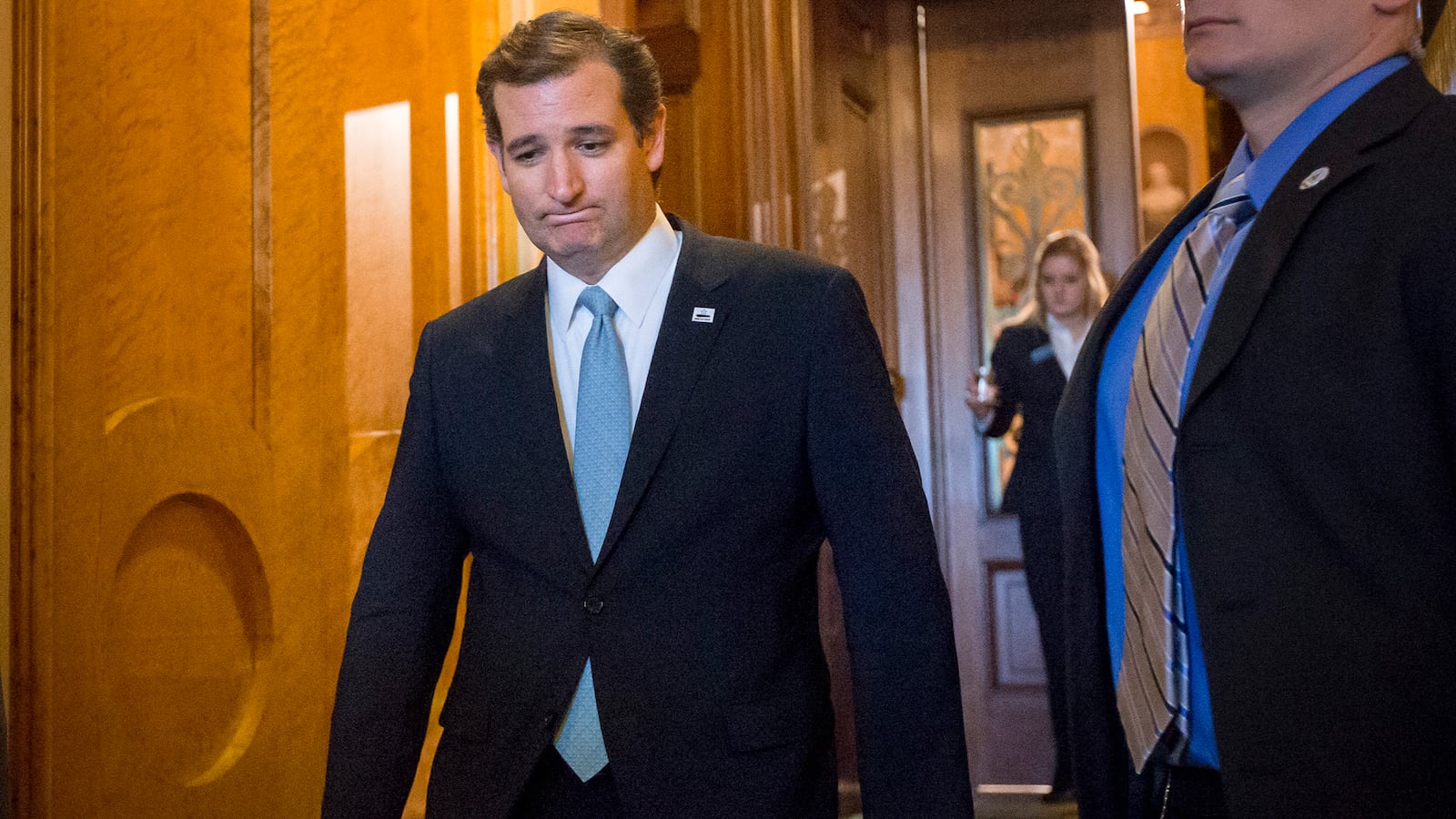

What do Tea Party darling Sen. Ted Cruz, droves of old-school Communist politburo members, and the straight-arrow, and therefore completely fictional, Sen. Jefferson Smith all have in common? They like to give long speeches. Really long speeches. Speeches so long, in fact, that no one knows what to say or do about them except report that the speeches are mighty long. And perhaps compare them to other really long speeches—the U.S. Senate winner being courtesy of Strom Thurmond, who in 1957 spoke, as part of a filibuster, against the Civil Rights Act for more than 24 hours. (Note that the Cruzathon was technically not a filibuster.)

Leaving aside the “why?” this raises a second question: How does a human being actually do this? How can you stay awake this long? Much less talk, even if you have what Senator Smith called "a few things I want to say to this body. I tried to say them once before and I got stopped colder than a mackerel." Plus, what about the mammalian issues standing up so long might create: the need to eat and drink a nourishing balanced diet? What about the bathroom issue? What about how boring it must be to talk that long?

Thankfully, ever since a San Diego teenager named Randy Gardner decided to see how long he could stay awake back in the 1960s, science has been fascinated with this topic. Gardner made it for 264 hours—and remains the listed heavyweight champion—because he involved a neurologist who observed his activity and turned it into a medical article. The report is fun to read, especially the patient’s sleep-deprived delusion that he was a running back, Paul Lowe, who starred then for the San Diego Chargers. But the punchline of the article was that, to the surprise of one and all, there was no lasting neurologic effect. Gardner basically slept off his all-nighter(s) like any self-respecting college student and got back to business, faculties intact. So those hoping that Senator Cruz will somehow damage his Tea Party mind by his long day’s journey surely will be disappointed.

The issue of how long a human voice can actually blab has not been studied in the same way. The larynx, a.k.a. voice box, is like any other muscle, more or less—those who don’t use it much and then try will be quite hoarse the next day; in contrast, those who are used to talking and talking and talking are in fine shape to keep talking even more. One might worry that we are raising a generation of the weak-voiced, given the presence of email and Twitter and et cetera for those who once enjoyed a good long two-to-three-hour chat on the phone. A veteran speechifier like Cruz, though, raised in the good old Ma Bell days, probably right now feels like a 10- and 15-mile runner who just pushed out and ran a first marathon—tired and achy and extremely self-pleased. But wanting to speak softly for just a little while. His risk for polyps and the sort of damage actors and singers seem to get is likely low, unless he makes a weekly habit of yakking away.

He need not worry about other aspects of his health, either. As long as he was sipping a little water, perhaps munching a piece of cheese, he will be able to withstand the semi-rigors of 21 hours without a lot of calories with no problem at all. Kidneys and heart and liver—all should sail right through.

Now to creature comforts. We know a lot about this because of Texas State Sen. Wendy Davis’s then-epic 13-hour filibuster to delay a vote on abortion restrictions. To keep herself free from the need to urinate or even the urge to go, she placed a urinary catheter into her bladder (she actually did much more than that—she also wore a back brace and running shoes for comfort). Commonly used in hospitals, these catheters are often referred to as “Foley catheters” to honor their inventor, Dr. Frederic Foley. They can really hurt to place and to remove … though a fetish for placing instruments into this delicate area does exist.

The Davis report spurred interest in this simple topic and led to what can only be called the definitive article on urination while giving really long speeches, courtesy of Mother Jones. The author, Hannah Levintova, thoroughly marches through the annals of urinary-collection devices, coursing past Strom Thurmond’s use of the hidden bucket (keeping a toe in the Senate chamber as he urinated to keep from being disqualified) to use of an “astronaut bag” by yet a third Texan, Bill Meier, during a 43-hour speech in 1977. It is likely that Meier wore either a Foley catheter or what is referred to in hospitals as a “condom catheter” or, mysteriously, as a “Texas catheter.” This works for men only by exploiting the anatomically advantaged male urethra to allow urine collection and flow without the tube jammed into a bladder. Click here for a YouTube video of how to apply one (warning: requires sign up and age verification).

As to the other issues—standing for that long, keeping a straight face for that long, thinking of things to say for that long—well, this too seems to be a politician’s natural gift, a facility for filling time and space with words, then even more words, a talent that crosses the aisle. So really there is no real health risk for pulling a Cruz.

Actually, it’s a scary proposition. What if, seeing how easy and how camera-friendly all that talk can be, more senators try it? Can C-SPAN keep up? Are there enough devices to handle the ingestion and expectoration? Is there enough e-ink to cover it? Only one thing is for certain: no matter what’s ahead—more non-filibuster filibusters, more virile speeches made dead into the camera, more causes worth standing up for, literally—the 100 senators of the United States are going to talk about it. A lot.