Brand new documents reveal some of the surprising targets of a Vietnam War-era secret NSA spying program—raising even more questions about the history and extent of America’s domestic surveillance program.

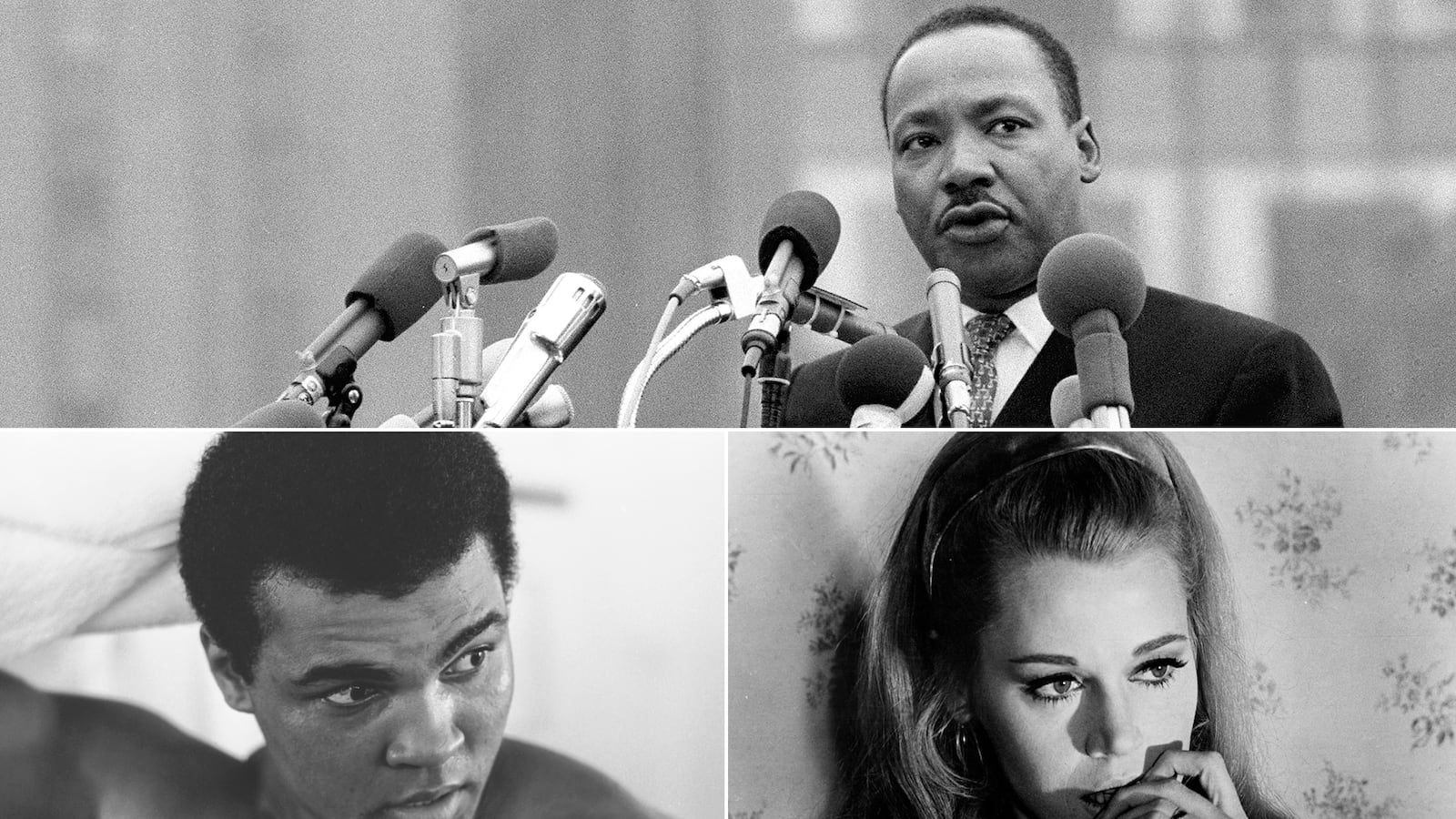

The declassified information Wednesday shows that prominent figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Muhammad Ali, and others were the targets of an NSA spying program called “Minaret,” created in 1967 at the request of then-President Lyndon Johnson, who was concerned that vocal Vietnam War critics may have had ties to foreign powers. The program was called “disreputable if not outright illegal” by some NSA officials and was ultimately shut down in 1973. But in the six years that Minaret was active, the NSA tapped the overseas phone calls of the over 1,600 people on its “watch list.”

Though Minaret’s existence was exposed in the 1970s, none of the NSA’s targets had been named until now, thanks to an eight-year push by the National Security Archive, a research non-profit at George Washington University.

Nowhere near all of the 1,600 names on the watch list have been released, those but those that have raise questions about what, exactly, the NSA was looking for. King and Ali were relatively vocal critics of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, but others like Sens. Frank Church and Howard Baker were fairly supportive of the war compared to some of their colleagues at the time. Unlike King, fellow civil-rights leader Whitney Young was not initially critical of the war and maintained a good relationship with LBJ. His views on Vietnam didn’t turn negative until 1969.

Certain members of the press were also subject to NSA surveillance, such as former New York Times Washington Bureau Chief Tom Wicker and Washington Post humor columnist Art Buchwald, who would use their platforms in print to lambaste the war.

Matthew Aid, a former visiting fellows at the National Security Archive who worked on getting details of the Minaret program released and edited, is perplexed by some of the names he saw on the list.

“Why was Tom Wicker of the New York Times on there? Or Art Buchwald?” he asked in an interview with The Daily Beast. “The worst that could be said about Art Buchwald was that he wrote good, biting, satirical columns. As far as I can tell, none of the seven individuals mentioned in that one paragraph had ever been accused formally or informally of being a threat to national security.”

Aid is concerned that the same thing is true of many of the still unnamed Americans who were spied on as part of the NSA’s PRISM program revealed by Edward Snowden and Guardian reporter Glenn Greenwald this year.

“We’ve learned now that a number of people have been convicted on terrorism charges based, in part, on NSA intercepts,” Aid said. “But what about the hundreds if not thousands of others who never got indicted or convicted?”

In Wednesday’s report, the National Security Archive’s researchers point to a document discovered at the Gerald Ford Presidential Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, that notes the overseas communication and travel of anti-war activists like Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden, David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Bernadine Dohrn, and Kathy Boudin, plus some African-American militants such as Eldridge Cleaver and Stokely Carmichael, were also monitored by U.S. intelligence agencies during that same period of 1967 to 1973.

Thursday, the Senate Intelligence Committee will hear a proposal by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy for new legislation that would put an end to the NSA’s controversial phone records collection program and instead encourage the use of a much more restricted phone records collection program under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. In announcing his plan earlier this week, Leahy noted that 1975 he made his first senatorial vote in favor of the Church Committee, which was created to investigate bad practices in intelligence gathering. The Church Committee was, of course, headed by Sen. Frank Church who, as we’ve just learned, was himself a target of NSA. (Ironically, Aid doubts Church had any clue that he’d been spied on when he decided to go after intelligence gatherers).

Aid said “it would be nice” if the Senate required the NSA to declassify the information gleaned from the PRISM program or at least the names of the people targeted, but isn’t getting his hopes up. “If we don’t have any public support, we’ll go ahead and do it ourselves,” he said, noting the only real issue is time. It took eight years after filing a Mandatory Declassification Request to get the documents that were released this week, and Aid said he’s had a Freedom of Information Act Request pending with the NSA for over a decade to get information on “Shamrock,” the Minaret program’s counterpart. But he knows the passage of decades doesn’t make these programs any less controversial or pertinent.

“There is still enormous interest in this subject, especially since Edward Snowden’s revelations, and that’s why we’re going to continue,” he said. “I’m convinced that what happened 40 years ago is still relevant today.”